Finding the Good Life Through Everyday Awe

A Recollection of My Most Pentecostal Experience Followed by Non-Nerdy Speculations on How the Emotion of Awe Transforms Us

1. Southern Sky

I hate it when real life plays out like cliché. But my most profound experience of awe occurred in one of the most predictable places: Yosemite.

I was moving back from LA to Michigan. I’d made the opposite drive five months prior for a worship internship at a church on Hollywood Boulevard.

The transition was the epitome of culture shock. I went from the endless open spaces of Big Rapids to sleeping on a mattress in 500-square-foot, 3-person apartment on the corner of Melrose and Kingsley. I was lucky if I could find a parking spot within 6 blocks. Then I’d have to wake up before 6am to walk those 6 blocks so the car didn’t get towed.

The internship was unpaid, so I raised support. But I didn’t raise enough. So rationing out the food budget was a constant stressor.

To top it off, I strained my vocal cords. And no matter how many ENT doctors I saw, none could offer a solution. By one doctor’s observation: “There’s nothing that can be ‘fixed.’ They just look like the vocal cords of an 80-year-old, not a 22-year-old.”

Up till that point, my career goals centered on becoming a worship leader. Now that life plan had dissolved, along with my job prospects, daily schedule, and life savings.

So I had to drive back home. The feeling wasn’t so much melancholy or depression as it was an apoplectic emptiness, of which I sat in for 30 hours of sand, rock, and lonely foliage.

I spent one night near San Francisco and woke up early to drive for Oklahoma.1 When I got near Yosemite, the song “Southern Sky” by (Sandy) Alex G came on – which is, to this day, still the most hauntingly beautiful song I’ve ever heard. And maybe it was just his strange croonings or that the mountain pass was unlike anything I’d ever seen or the way the rising sun superimposed itself on everything, but I felt like I received permission to exhale my constant headache of stress and letdown — as if an immediate wonder shrunk all self-concern.

The limitations of the English language are never more apparent than when I try to articulate what I felt. I got so overwhelmed by God’s presence that I slowed down, pulled over, and just shook. It felt like fireflies were swirling in the space between my eyes and hairline and I stepped out of the car just to feel grounded in the sediment and breathe the un-smogged air.

From that moment onward I felt Divine assurance that it was all worth it – that everything was and would be okay.

Now, I’m entirely convinced this experience was something beyond what can be reasonably explained by science. It fits psychologist William James’ description of a mystical experience in that it was “ineffable” (i.e., impossible to articulate). And I’m perfectly content that explanation.

But years later I came across some research on “awe.” And I realized that this was probably the only emotional category that was somewhat similar to my experience.

As I dug in further, I found that awe wasn’t just a feel-good dose of wonder; it’s an emotional phenomenon that can transform the lives we lead — especially when it’s attached to a spiritual framework.

Awe isn’t easy to manufacture, but it can be – and it even seems like it should be. Pursuing everyday awe is a crucial compass for finding the good life.

2. Religious Emotions

Along with gratitude and elevation, awe fits within a unique branch of feelings that have been called “religious” or “moral” emotions.2

Unlike other emotions, this trio causes a self-transcendence that takes us beyond our immediate concerns – turning our thoughts toward more altruistic, spiritual, and communal purposes.3 Importantly, they all have a synergistic relationship with our spirituality: the more we feel awe, the closer we feel to God, the closer we feel to God, the more we feel awe.4

While the whole trio is crucial, some believe awe is the most important of the three.5

3. What Is Awe?

Awe is the sense of being in the presence of something vast, powerful, or beautiful that transcends our understanding of reality.6 It’s almost like Immanuel Kant’s idea of “the sublime” — a mixture of joyous wonder and shock that overshadows our day-to-day anxieties.7

Awe falls into two main categories: vastness (being in the presence of something that makes us feel small) and accommodation (encountering something that forces us to alter our understanding of reality to make room for it).8

For example, awe might come through witnessing beauty in nature (like the Grand Canyon or Pictured Rocks),

art (like the Sistine Chapel or Bach or the film Boyhood), or

major emotional events (like the birth of a child or going away to college).

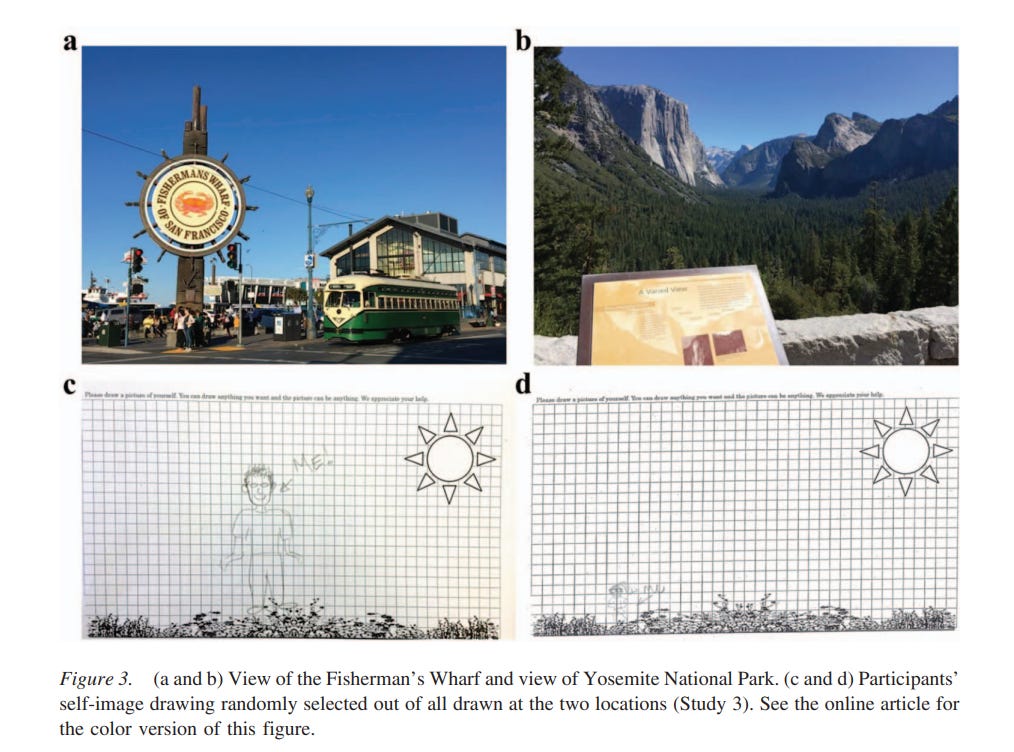

When psychologist Yang Bai studied awe, she asked 11,000 participants to draw a picture of themselves in relation to the sun. One group was asked to do this while in San Francisco, while the other group was in Yosemite Park.9 The group in Yosemite drew themselves about a sixth of the size as the San Francisco group.10

This is because awe literally makes us see ourselves as small – as people who have less control or agency over the universe.

Vastness doesn’t have to be physical. It can also be temporal — like when the novelist Marcel Proust was triggered into a fit of euphoric nostalgia after eating a madeleine. It flooded him with early memories of his aunt’s madeleines: the sights, sounds, and sensations of childhood all came crashing down. This single experience left him so awestruck that it inspired him to write the 1,267,069 words of In Search of Lost Time.11

Sensations that trigger our contemplation of time passed is a big source of awe. This might explain why nostalgia porn has grown into such a popular genre (think Disney’s Star Wars reboots or the revival of 80’s synth pop in bands like Lany).

The other component of awe, accommodation, might illuminate why conspiracy theories, UAP sightings, and paranormal stories amass such a passionate following.

Unexplainable events break our brain’s molds for how we think the world should work.12 And this feels surprisingly good.

Like Einstein said, “The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and science.”

There’s an odd comfort in realizing we don’t have it all figured out; hence The X Files’ Agent Mulder’s favorite saying: “I want to believe.”

Accommodation helps us envision a more enchanted world, which is simply more thrilling than a strictly material one.13

The public theologian Russell Moore also believes accommodation is responsible for why young adults come back to the church after having children.14

The birth of a child is more than enough to jostle the cold rationality of our beliefs. It skews us toward a wonder that there might be more purpose in the universe — and that Love might be its absolute center.

4. We’re All [Un-awe-inspired] Thomas Now

Scientists have only recently started taking awe seriously.

Dacher Keltner, the leading scientist in awe studies, noted that academics pushed awe to the wayside because emotions research arose in a zeitgeist where they prioritized a “hyper-individualistic, materialistic, survival-of-the-selfish view of human nature.”

And since awe forces us to “devote ourselves to things outside of our individual selves,”15 many considered it a useless appendage to the more important human potentials like getting ahead or amassing power.

Which is a frankly sad and hollow view – but it’s a mood that continues to this day.

This is why, in our post-Enlightenment era of “disenchantment,”16 awe is less easy to come by. Our culture’s educational paradigms don’t train us to see magic in the world. They usually do the opposite: training us to reject mystery and wonder and narrow everything down to its lowest rational denominator.

So, finding awe requires reverse training – of pausing long enough to see the intricacies of the leaf that just fell, of taking moments to study the euphoric panic in your nephew after assembling a Lego, of intentionally recounting key moments of your relationship with your spouse, of going on airplane mode nature walks.17

This is where awe finds a lot of overlap with childlikeness. When Jesus said “becoming like children” was a prerequisite for seeing the kingdom of heaven (Matt. 18:3), He might’ve had in mind the way a child’s endless capacity for wonder allows them to inhabit life unchained from the constraints of rationality.

The most challenging part of triggering awe is that the average attention span is about 7-9 seconds, and it can take around 14-20 seconds of intentional focus to start feeling awe.18

Yet awe is literally everywhere; it simply requires, on our part, the “discipline of notice” — pausing long enough that our disenchantment lenses fade and we see the remarkable in the ordinary.

5. Contemplation, Architecture, and Awe Walks

Awe is euphoric even apart from Divine intervention; but I believe that when awe is aimed toward or even experienced with God — as in my experience in Yosemite — its wonder factor reaches new levels of profundity.

Even further, awe is still beautiful when alone, but it is mesmerizing when it’s shared with others.

Think about some of the best moments you’ve had – receiving a job offer, getting accepted into the dream school, figuring out you’re pregnant – and consider how muted those experiences would’ve been if you weren’t able to share them.

This is thanks to a concept Emile Durkheim, the father of sociology, called “collective effervescence.” It’s the kind of mutual buzz we feel with others amidst powerful shared experiences.19

Across 26 distinct cultures, people reported feelings of collective effervescence at religious events like collective prayer, group singing (especially when it’s acapella), weddings, funerals, and community meal gatherings.20

Experiencing awe as a group makes us feel like a collective self, an “oceanic ‘we’” of the same mind with others.

This “oceanic feeling” is one of the more profound sources of lasting joy humans are capable of experiencing. Connection of this variety is also one of the most common features seen in those who live the happiest and longest lives.21

Which made me want to ask this question: if collective effervescence is really so important to life, are there any ways Christians can incorporate awe into our collective spiritual practices?

Yes — a lot, actually.

I narrowed it down to three: (1) contemplation, (2) architecture, and (3) awe walks.

Contemplation is the practice of placing unilateral awareness on God.

Thomas Merton called it “spiritual wonder” — the feeling of “spontaneous awe at the sacredness of life, of being.”22

There are many definitions, but broadly speaking, contemplation is any kind of gazing toward, beholding of, and steeping within the presence of the Triune God.23

Which, I know, sounds vague. When I teach contemplation, I usually just tell people to picture what comes to mind when a monk is joyfully practicing the presence of God.

But it’s more elastic than that description. It can also look like meditating on Jesus’ life or God’s face, euphorically swaying to music, or breath prayer.

Usually contemplation is depicted as a solitary practice, but recently I’ve been wondering if this is somewhat of a narrow idea. As Paul wrote,

And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another (2 Cor. 3:18).

Lots of contemplatives use this verse as their jumping off point. Its theology partly inspired generations of monastics toward silence and solitude.24

But I find it interesting that every verb in this section is in the first-person plural we.25 We who contemplate the Lord are being collectively transformed.

So maybe it’s a team sport. And if we look throughout Christian history, group contemplation isn’t all that enigmatic. Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross even advocated for shared silence within their communities in order to foster a one-mindedness.26

This isn’t meant to diminish the power of solo contemplation (just read Jesus’ wilderness journey in Matt. 4, Luke 4). It’s to argue that we shouldn’t shy away from shared contemplative practices. And if we prefer solo, we could even set times to contemplate as a community, separately.27

Architecture.

Christians used to have a better grip on the importance of architecture than modern Protestants. In fact, many old church buildings were specially designed to induce wonder.

Awe-inducing architecture was once a priority. Just think about Notre Dame, the Las Lajas Sanctuary, or the Church of the Assumption.

The goal wasn’t to stack brick on top of brick and call it a sanctuary. The architecture was as important as any other part of church planting because it was assumed that its sheer beauty might draw people closer to God.

And as research shows, it works. People feel awe over architectural beauty as much as natural beauty.28

God gave us the wiring to find awe through the beauty of creation; He, in turn, also gave us the potential to remold creation’s raw materials into awe-inspiring designs.

A gorgeous church setting isn’t a must. But anyone who’s toured cathedrals across Europe or the Mid-East will tell you there’s an undeniable power in well-designed spaces. In the same way we might hear a Gospel hymn and sense the Spirit was working through its writer, so we can stare into vast ceilings of Notre Dame and know the Spirit was in the architect.

I’m far from the first to suggest this, but maybe it’s time for a rejection of the industrial revolution’s obsession with pragmatism and make an effort to design our spaces of worship to invoke awe.

Regal designs will, of course, attract criticism. Shouldn’t the money be used to serve the poor? Sure, and they should’ve made the tabernacle out of mud rather than expensive metals and Mary shouldn’t have wasted her expensive oil.

Just because architecture is beautiful doesn’t mean it’s wasteful; it might just be the best way to create a space for inspiring group awe.

Lastly, awe walks.

This one is as simple as it sounds: put down your screens and walk. As the coolest couple on all of Substack (

& ) wrote recently,Walking redirects our muddled thoughts outward toward the scenery we are passing. It helps us to connect with each other in shared conversation and rhythmic pace. It echoes history and tradition through a most simple movement that has remained “essentially unimproved since the dawn of time.” Importantly, the act of walking not only restores our minds, but helps to build up internal resilience and resistance against algorithmic mental slavery.29

Keltner prescribes “awe walks” as an antidote to our disenchanted malaise. Awe walks don’t even require majestic locales. All they require is freedom from screens, a path to stroll, and a commitment to notice the scenery we’ve taken for granted.

Awe walks have an astounding number of benefits. Yang Bai even notes their potential to shift our minds from individualistic and reductionist styles of thinking toward seeing everyone as dependent on one another or interrelated.30 It’s one reason why it’s easier to make friends while out hiking — we literally see them less like strangers and more like another member of our complex social web.

Of the thousands of reports of awe accumulated over years of research, none included screen-induced awe. But many — many — reported awe while out on walks or hikes. Thus, finding awe can be as simple as scheduling nature walks with community. We all, by Peco and Ruth’s suggestion, should join the walking revolution.

Awe can’t fix all our problems, but it can make us cherish the things that make life most worth living.

And when awe is attached to religious experience, it becomes even more potent. As William James noted over a century ago, mystic experiences can’t help but modify our inner lives. Each experience gives us a deeper understanding of who God is, and this, in turn, grows us incrementally more into His likeness.

Which brings us right back to what Paul said: that we who behold the Lord are being transformed into His image, from one stage of glory to the next.

Thanks for reading! For the article on gratitude, see here. Check back in next week for the article on elevation!

I realize the geography makes no sense. I’d never seen San Francisco, so I drove up the 1 to experience it before I went back East. Then I made the trek to Oklahoma because I had a friend there I could crash with.

Sara B. Algoe & Jonathan Haidt, “Witnessing Excellence in Action: The “Other-Praising” Emotions of Elevation, Gratitude, and Admiration,” Journal of Positive Psychology 4 no. 2 (2009): 105-127; David DeSteno, How God Works: The Science Behind the Benefits of Religion (New York: Harper, 2022), 58-61.

K. Piff, Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, and Dacher Keltner, “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 108, no. 6 (2015): 883-899.

DeSteno, How God Works, 59-64.

Dacher Keltner believes this. I see where he’s coming from, but I think the trio upholds each other.

The best resource on awe is Dacher Keltner, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How it Can Transform Your Life (New York: Penguin, 2023).

Immanuel Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, trans. J. T. Goldthwait (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2004), 46.

Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (New York: Vintage, 2012), 264-265; Dacher Keltner & Jonothan Haidt, “Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion,” Cognition and Emotion 17 (2004), 297-314.

We’ll tiptoe around the fact that these are two of the locations mentioned in my own awe story. Weird, weird. I shuddered a bit when I noticed.

Yang Bai, Laura A. Maruskin, Serena Chen, Amie M. Gordon, Jennifer E. Stellar, Galen D. McNeil, Kaiping Peng, & Dacher Keltner, “Awe, the Diminished Self, and Collective Engagement: Universals and Cultural Variations in the Small Self,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113, no. 2 (2017): 185-209.

Double the word count of War and Peace, fyi.

Yannick Joye and Jan Verpooten, “An Exploration of the Functions of Religious Monumental Architecture from a Darwinian Perspective,” Review of General Psychology 17, no. 1 (2013): 53-68.

Paul K. Piff, Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, and Dacher Keltner, “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 108, no. 6 (2015): 883-899.

Russell Moore, Losing My Religion: An Alter Call for Evangelical America (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2023).

Keltner, Awe, 6.

This is such a buzzword right now and I’m really not sure why. The term was originally used by Max Weber to describe the post-Enlightenment world which naturally assumed an absence of spirituality.

Keltner, Awe, 128.

Tea Sindbæk Andersen & Jessica Ortner, “Introduction: Memories of Joy,” Memory Studies, 12 no. 1 (2019), 5-10; Megan E. Speer & Mauricio R. Delgado, “Reminiscing About Positive Memories Buffers Acute Stress Responses,” Natural Human Behavior 1 (2017): 0093; Mauricio Delgado, et. al., “Nostalgia Rewards the Brain,” Nature 515 no. 11 (2014); see also Adam Alter’s Irresistible.

Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. J.W. Swain (New York: The Free Press, 1912).

Keltner, Awe 6, 11.

See The Good Life by Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz (will post more in depth essay about this in approximately a month).

Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation, 1.

I almost guarantee that contemplative experts would loathe this definition. For how widespread the practice is, it is quite difficult to nail down precise definitions. My favorite resource on the subject is Martin Laird’s trilogy: Into the Silent Land, A Sunlit Absence, and Ocean of Light. While I disagree with several of Laird’s finer theological points, this trilogy is an overwhelmingly gorgeous meditation on contemplation in the Christian life.

Along with, of course, Jesus’ wilderness battle with the devil.

Colin G. Kruse, 2 Corinthians: An Introduction and Commentary, 2nd edn. (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale, 2024), 137.

See Paul-Marie of the Cross’ Carmelite Spirituality in the Teretian Tradition.

3 months of posting on Substack is starting to make me sound real catholic.

Joye, Verpooten, “An Exploration of the Functions of Religious Monumental Architecture from a Darwinian Perspective,” 53-68.

Frances E. Kuo & Taylor A. Faber. "A Potential Natural Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Evidence from a National Study." American Journal of Public Health 94, no. 9 (2004): 1580-86; Yang Bai, et al., “Awe, the Diminished Self, and Collective Engagement: Universals and Cultural Variations in the Small Self." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113, no. 2 (2017): 185-209.

Love this piece. I had the most incredible experience of “collective awe” at my grandmother’s funeral this summer when I sang “It is Well with my Soul” with a few dozen of my cousins, while looking out on the beloved faces of our parents crying while contemplating our family matriarch, the gift of resurrection, and all the incredible intertwined emotions of grief and a deep joy and the gratitude we all felt to be a part of such an incredible moment. It’s a lot like when you saw the natural beauty of Yosemite—it’s almost impossible to put into words how it feels.

This excellent post about cultivating awe reminds me of an experience of religious awe I had back when I was an atheist that came from looking at something very small rather than very big.

I was training in electron microscopy, and we had to prepare various samples and then look at them using electron microscopy. Of course I had seen electron microscopy images before, so I thought I knew the kind of thing I would be seeing.

One of the samples my instructor had me work on was pond water, because there are a lot of microbes in pond water and preparing the samples involved all the techniques I had been taught. I also thought I know what I would see here, too, because what aspiring biologist hasn't seen critters in pond water through a microscope? So I knew I'd see ameobae, paramecia, that sort of thing.

Except when I zoomed in, the paramecium wasn't the vague floaty shape I knew from light microscopy. It was cute, fuzzy like a kitten.

Zoom in more. Each of the paramecium's hairy cilia are delicately textured. Each one is nested in its own socket. Zoom in more. Each socket has its own intricate details. Language fails. I just can't stop looking. It's so beautiful. The layers never stop.

Now zoom out. In this tiny sample there are hundreds? thousands? of paramecia. And in the pond millions or billions? And I felt the weight of knowing that they are all as intricate as this one.

I felt dizzy and slightly sick, like I was at the top of a very high precipice, about to fall. How could the world be filled with so much extravagant beauty, in the tiniest details of tiny organisms, virtually none of which are ever seen?