Your Great-Grandma Thought Elvis Was the Devil

How Morals Change Over Time & How to Know When They Change Too Far

1. the shift

I don’t know your great grandma, but she probably didn’t like Elvis.

I don’t know your grandma, but I’ll bet she liked Elvis.

Over Labor Day, I got to hangout with my grandma and she told me a story, one I love very much. Apparently, when she was 18 or 19, she and her friends went to Palm Springs to see Elvis in concert – and she hid the whole excursion from my great grandma. My grandma even paid way too much to rent a specific house that overlooked where Elvis was staying. After the concert, their friend group climbed a ladder to sit on the edge of the roof to try and catch a glimpse over the field of cacti and lilacs. Sadly, Elvis never showed. And my great grandmother never found out.

Nowadays, we barely remember the shock that rock & roll was to our culture’s nervous system.

It was so much more than energetic pop music; it represented sexual liberation, multiracialism, teenage rebellion.1

At the center of it was, of course, the King. To this day, there’s still no modern figure that can compare in terms of polarization.

Young girls were so infatuated that they started riots at every single show from ’55-’57. The young men, in reaction, got so jealous that they organized protests and on one occasion even firebombed Elvis’ car in Lubbock, Texas.2

People considered Elvis so dangerous that one public official commented, “His music is deplorable…It fosters totally negative and destructive reactions in young people.”

Do you know who said that last line?

It wasn’t a bitter geriatric Christian, but the Rat Pack’s own Frank Sinatra. You know, the musician who’s famous for womanizing his uniquely passionate fan base of young girls, consuming preposterous sums of alcohol from sunrise to sunrise, and gambling to suppress his demons.

Sinatra was only one generation removed from Elvis – and they even had a lot of similarities. Sinatra was controversial, and just like Elvis, had the viral mugshot to prove it.

But then everyone got used to having him around. The moral panic subsided. In other words, the culture slowly metabolized Sinatra – just like how they would soon adjust themselves to Elvis.

Now, in my lifetime, I’ve never met someone who felt morally compelled to stop listening to Elvis, The Beatles, AC/DC or Nirvana. For the most part, we’re desensitized to the fact that there was ever even a moral component in rock & roll music.

When I read about this, I got super fascinated about how morals change over time: where we draw the line in the sand and how much time it takes for that line to shift. As we’ll unpack, it apparently takes around 15-20 years for moral status quos to turnover – about the age gap between your great grandma and grandma.

I also want to look at how the church fits within these ethical shifts. But what I’m mainly curious about is how and why the bar moves and how to know when it moves too far.

2. the gist

Some argue that there’s no longer a line, a moral bar, or stigma (the “WAP” music video is pretty convincing).

But there’s still a bar and, chances are, there always will be. Against popular opinion, we need limits. Societies without them don’t last long.

But that doesn’t stop us from continually trying to undo them. Historians Will & Ariel Durant, after their lifelong mission to condense human history into 11 volumes, decided to condense history even further into a slim, 100-page book about the lessons they’d learned. They wrote:

Out of every hundred new ideas ninety-nine or more will probably be inferior to the traditional responses which they propose to replace. No one man, however brilliant or well-informed, can come in one lifetime to such fullness of understanding as to safely judge and dismiss the customs or institutions of his society, for these are the wisdom of generations after centuries of experiment in the laboratory of history.3

The restlessness that causes us to deconstruct old taboos might just be etched into human DNA.

Every generation can’t help but notice the flaws the last generation leftover. And so they invariably resign themselves to an irritable discontent about the system until those flaws are abolished.

What they often don’t realize is that many of those flaws are there simply because reality is flawed in general. Which is because life, the world, and time are still reeling from The Fall (see Genesis 3) – not necessarily because things are uniquely flawed due to some bad legislation, oppressive ideas, or parental idiocy.

So, even though things might be going pretty much alright, the young misinterpret the inescapable discontent of living as a chain reaction of the past generation’s mistakes that now requires repairing.

This is the tension that creates the back-and-forth pattern of history. When one generation pushes the dial too far one way, the next over corrects into the opposite direction.

This isn’t just speculation; there’s even research to support it.

In their studies on moral behavior from 1900-2007, scholars Melissa Wheeler, Melanie McGrath, and Nick Haslam found that moral shifts usually happen every 15-20 years.

The transitions happen like a seesaw that teeters back and forth between liberal ethics (which are more concerned with individual freedoms, social justice, and equality) and conservative ethics (more concerned with loyalty, privacy, obedience, and tradition).4

Which is like a living example of one of Plato’s warnings: “The excessive increase of anything causes a reaction in the opposite direction.”5 Or in the Durants’ words, “Puritanism and paganism – the repression and the expression of the senses and desires – alternate in mutual reaction in history.”6

3. change in the pattern

Yet, despite this back-and-forth pattern, what we’re seeing today is slightly different. The pendulum is now pushing the moral compass slightly more liberal and slightly less conservative with each swing.

As the cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker has shown, every generation for the past 200 years has become slightly more liberal than the last.7 Meaning, every new generation has inched further from their parents’ moral taboos and toward a hands-off, self-expression-driven status quo.

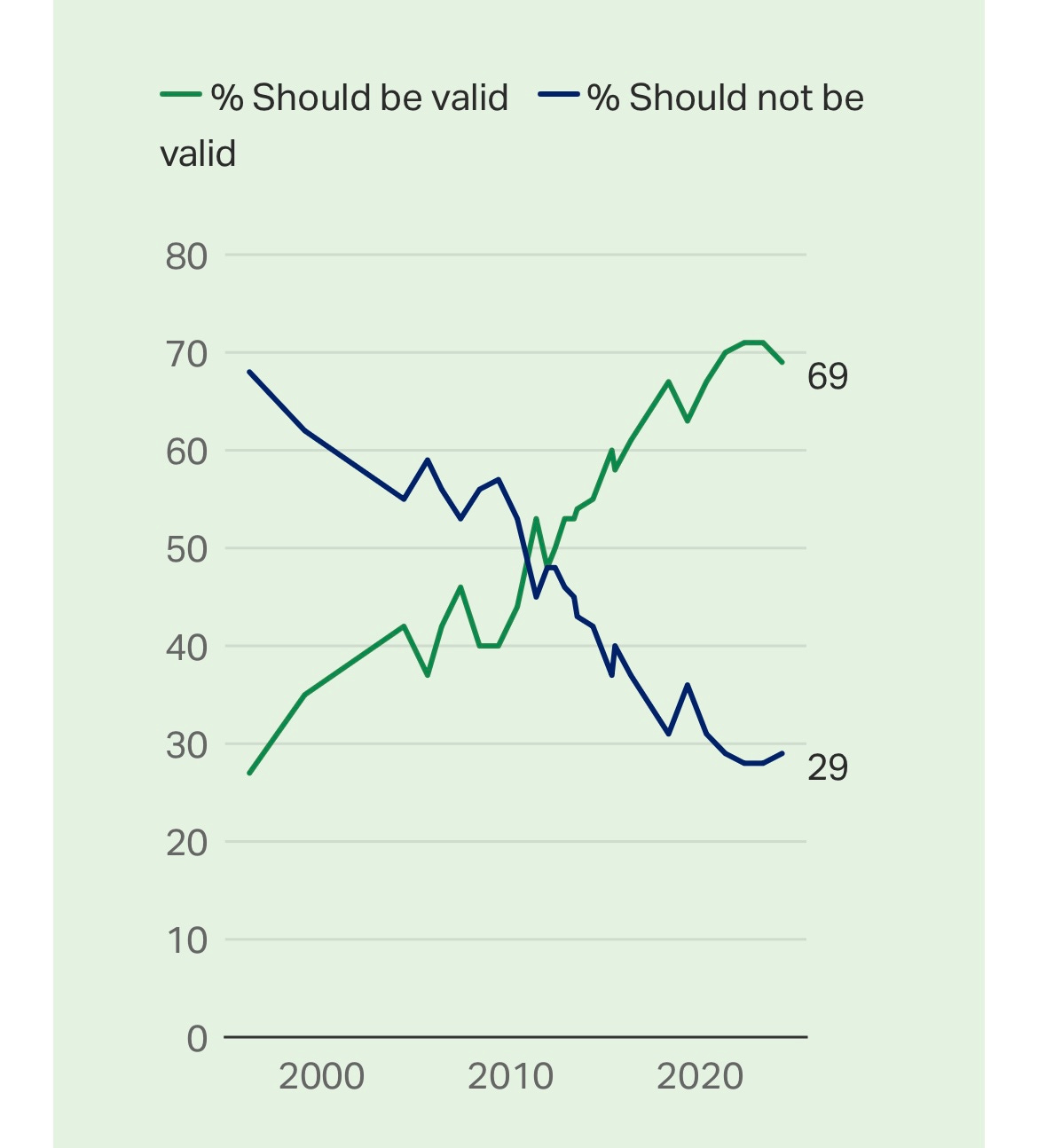

For example, let’s look at how this has played out in opinions on same-sex marriage.

In the early 2000’s, only 26% of people thought same-sex marriage should be considered valid.

As of 2024, only 29% of people thought same-sex marriage should be considered invalid.

Again, that’s around the time lapse between your grandma and her mom.

Then it only took a few more years for the entire rationale behind the anti-same sex marriage stance to shift. As a 2017 study examined, the holdout group that still opposes same-sex marriage doesn’t base their belief on moral grounds – they just dislike change. In other words, they don’t disapprove of same-sex marriage because the Bible tells them so, but because they miss the “good ole days.”

The scholars behind the study offered this prediction, “Once same-sex marriage is firmly established as the status quo, even those citizens who hold conservative preferences should eventually come to support it.”8

They’re probably not far off. Two years after their study, about 66% of white mainline Protestants and 61% of Catholics said they supported same-sex marriage.

Then a more recent survey found that while 11,893 American Christians opposed same-sex marriage, 10,666 strongly favored it. That’s only a fraction off from a 50-50 split.

All this to say, the views on same-sex marriage among Christians – even conservative Christians – are getting more relaxed.

As are their views on abortion. In fact, the majority of all religious groups in America today believe that abortion should be legal in all or most circumstances. The only holdouts are white evangelical Protestants (73%), Mormons (70%), and Jehovah’s Witnesses (75%).

Even though the majority of Americans still (surprisingly) identify as Christian,9 their ethics seem increasingly malleable – shaped by personal preference, political tribe, and cultural moment.

4. moral foundations

Okay – you get the idea. Now, let’s look at the social science (which might also sound boring, but payoff it will).

Thanks to groundbreaking work from moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt,10 we now understand that our moral compasses are mostly shaped by personality, bias, and experience rather than some easily ascertainable right and wrong.11

Everyone finds themselves somewhere on a spectrum of five (or seven) different “moral foundations” that influence the ethical outlook they’ll drift toward in day-to-day life.12

One important foundation for us to understand is called “Purity.” It’s the part of our ethical outlook that’s concerned about physical/spiritual sanctity, cleanliness, virtue, and innocence. It’s the kind of moral language people pull out when discussing a fetus’ right to life or the need to preserve the nuclear family.

But in recent years, Purity language has been on the decline.

For example, while political speakers increasingly evoked Purity-related language when talking same-sex marriage from 1996-2004,13 there’s since been a substantial decrease.

Year by year, our public conversations – including television news, political speeches, publications, song lyrics, and even books – are becoming less concerned with sanctity, preserving innocence, spirituality, and respect for tradition.

So much so, in fact, that the Republican Party recently revised their platform’s stance on traditional marriage and abortion of all Purity-related, moral language.

Now, if we were only judging by the Purity foundation, we’d be safe in assuming that Western society is becoming less moral.

But in many other ways, we’re becoming more moral as a society. Some even call the period from 2014 to now “The Great Awokening”14 because of the ways other moral foundations like fair treatment for disadvantaged groups (what Haidt calls the “Fairness” foundation) and our collective desire to keep kids safe (the “Care” foundation) have catapulted into collective common sense.

So, it’s not that we’re in an entropic spiral into a total moral tundra. In reality, all we can be certain of at this point is that our moral concerns are moving away from spirituality and holiness and toward fairness and individual happiness.

5. for better or for worse

While many moral standards will still likely shift back and forth by generation, there’s no way to be sure whether some are permanent. After all, despite some minor concerns over preteens’ 1D fandom, moral dread over rock & roll and sexy male singers never really swung back.

The political scientist Ryan Burge predicted that in the same way that recent generations have ever so slowly shifted their values to allow women to preach (which was surprisingly taboo in many Protestant circles just 20 years ago), so churches will likely begin doing the same with same-sex marriage and abortion. They might become moral issues we chuckle at for ever having fussed over.

This happens more than we’d like to admit.

Two decades ago Christian youth were almost unanimously barred from enjoying Harry Potter. Nowadays even conservative publications like The Gospel Coalition or Desiring God put out articles praising the series.

Similar shifts are seen in the church’s general opinion on women in ministry, alcohol, tattoos, and bikinis – all of which occurred in almost the exact same time frame.

Many of these issues followed the Elvis cycle: (1) initial moral panic, (2) outrage gradually subsides because the panic doesn’t cause change (and in many cases, even makes the taboo more popular because controversy sells), (3) then a respected figure in the outrage party admits to enjoying Elvis/wearing a bikini/getting a tattoo, and (4) eventually the moral issue is seen as a belief held only by fringe radicals.

So, are these changes for the better? Or are there some changes that we’re growing desensitized to that we should hold the line on? And how can a church discern whether to go with the cultural drift or stick to tradition?

Of course, some change is inevitable. I’m not aiming to catastrophize every single moral shift. After all, many changes are wonderful (women in ministry comes to mind).

However, on a serious note, it’s pretty well studied that any society that refuses to draw a moral line in the sand – to set limits, barriers, and restraints – will not live long & prosper.15

As the father of sociology Emile Durkheim found, the less constraints citizens have in their lives – be it religious boundaries, familial ties, communal responsibilities, existential purpose – the more likely they are to feel listless, alienated, and depressed.

The most shocking aspect of his studies revealed that constraints had a direct correlation with suicide rates.

The less constraints, the higher the possibility of suicide.16

The theory distributed so evenly that Catholics, who are bound to more systematic practices and communal responsibilities, took their own lives less than Protestants, who are less scheduled, regimented, and communally bound.17

A life without boundaries or resistance is like a plant without a trellis; with no walls keeping it in line, it gets unruly and misshapen. As the novelist James Baldwin wrote, “There is nothing more unbearable, once one has it, than freedom.”18

As frustrating as they are to the young or libertine, moral guardrails protect us from the whiplash of overindulgence. The philosopher Edmund Burke said something similar:

Men are qualified for civil liberty, in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites…. Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things, that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.19

In other words, a culture that permits everything becomes ruled by its permissions. As the apostle Paul put it, “‘All things are lawful for me,’ but not all things are helpful. ‘All things are lawful for me,’ but I will not be dominated by anything” (1 Cor. 6:12). To modernize, it’s like he’s saying, “I can do most things I want, but I use discretion because lots of things I can do are downright stupid.” Just because Christians have freedom doesn’t mean everything we’re free to do is good.

This might help explain why churches that keep stricter guidelines tend to be more successful and longer lasting than churches that are more laissez-faire.20

As Professor Laurence Iannaccone demonstrated in a large study, churches that erect more boundaries, rules, and moral expectations prosper more than churches that don’t.

Same thing goes for AA: if the 12 steps aren’t respected, the community falls apart.

In other words, maybe churches, like individuals and society, benefit from having more constraints – even when we think we’d be better off with less.

Which, all put together, points to why I’m generally pessimistic that undoing more and more traditional guidelines is always going to do good for the church – let alone society – in the long run.

So, when it comes to discerning where to draw the moral line, the Bible is, of course, the gold standard (Matt. 5:19).

But in the areas where the Bible leaves ambiguities – and there are more than we like to admit – we’re tasked with using discernment to weed out the right from the wrong.

As theologian Olivier O’Donovan argues, “Christian freedom, given by the Holy Spirit, allows man to make moral responses creatively.”21

Which is an enormous responsibility.

While certain moral issues are more black and white (murder, adultery, etc.), the modern Christian is tasked with creatively and lovingly responding with Christlikeness to the gray areas. And we do this primarily through general wisdom as well as reliance on the power, wisdom, and guidance of the Holy Spirit (John 14:26; 16:8-11, 13).

While this process will create more division and heated debate within a church that’s already pretty well known for division and debate, we can rest assured that – at least, some day – we’ll recognize the efficacy of our moral decisions through the fruit they produce (Matt. 7:15-20).

In other words, the paths we follow will inevitably reveal, for better or for worse, whether our choices have led to greater love for God and others, or less love for God and society at large. These two factors – (1) devotion to God and (2) human flourishing – might be our best signals.22

So essentially, the oscillating levels of devotion to God and human flourishing might be our best guide to the kind of fruit our moral transitions produce.

Morals can’t help but shift over time. But the church is responsible for holding the line in all the right areas. Even if it makes us look ridiculous, antiquated, or frustrating, we have a responsibility to live and move and have our being as moral exemplars of the Kingdom in this world – even if the world rejects it.

Peter Harry Brown & Pat H. Broeske, Down at the End of Lonely Street: The Life and Death of Elvis Presley (New York: Signet, 1997), 55.

Roy Carr & Mick Farren, Elvis Presley: The Complete Illustrated Record (New York: Plexus Publishing, 1989), 12.

Will & Ariel Durant, The Lessons of History (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968), 35.

Melissa Wheeler, Melanie McGrath & Nick Haslam, “Twentieth C50.entury Morality: The Rise and Fall of Moral Concepts from 1900 to 2007,” PLoS ONE 14 (2019): e001.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desomond Lee (London, UK: Penguin, 2007), 8.555b-566e.

Durant, The Lessons of History, 50.

This point is discussed at length throughout Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York: Penguin, 2019).

Jojanneke van der Toorn, John T. Jost, Dominic J. Packer, Sharareh Noorbaloochi, & Jay J. Van Bavel, “In Defense of Tradition: Religiosity, Conservatism, and Opposition to Same-Sex Marriage in North America,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43 no. 10 (2017): 1455-1468 (at 1465).

Ryan Burge, “Most Americans Are Still Christians,” Graphs About Religion, November 30, 2023, https://open.substack.com/pub/ryanburge/p/most-americans-are-still-christians?r=2mvy4l&utm_medium=ios.

Jonothan Haidt & J. Graham, “When Morality Opposes Justice: Conservatives Have Moral Intuitions that Liberals May Not Recognize,” Social Justice Research 20 (2007): 98–116.

This is such a can of worms to open and I can’t give it adequate attention here. According to Christian theology, we believe that a universal sense of morality is “written on our hearts” Rom. 2:14-16). But this “law” is more concerned with macro, large scale ethical decisions as opposed to minor issues. Take for example the fact that Paul insists that you don’t need to worry about eating food sacrificed to idols (1 Cor. 10; Rom. 14). And yet, he also says to not eat food sacrificed to idols if someone near you has a weak conscience. So, eating food sacrificed to idols isn’t wrong; but eating food sacrificed to idols in front of certain situations is wrong. This is indicative of an approach to ethics that might be more in line with casuistry as opposed to innate, universal black and white principles. Thus, I find Haidt’s theory, in which our moral leanings concerning (typically) minor issues is based less on universal maxims of right vs wrong as opposed to an enormous ethical sandbox that all, in one way or another, leads back to Christ as the model of all perfect ethical behavior.

M. Atari, J. Haidt, J. Graham, S. Koleva, S.T. Stevens, & M. Dehghani, “Morality Beyond the WEIRD: How the Nomological Network of Morality Varies Across Cultures,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 125 no. 5 (2023): 1157–1188.

J. Garten, R. Boghrati, J. Hoover, K. M. Johnson, & M. Dehghani, “Morality Between the Lines: Detecting Moral Sentiment in Text,” Proceedings of IJCAI 2016 Workshop on Computational Modeling of Attitudes (2016).

I’m not sure if he’s the first to have said this, but the historian Tom Holland uses this phrase a lot.

For an examination of how and why moral behaviors correlate with laws, see Frederick Schauer, The Political Risks (if any) of Breaking the Law, Journal of Legal Analysis 4 no. 1 (2012): 83–101. For a look at how rules are crucial to the successful continuity of any species, see Claudio Tennie, Josep Call, & Michael Tomasello, “Ratcheting Up the Ratchet: On the Evolution of Cumulative Culture,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (2009): 2405-2415.

Robert Alun Jones. Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1986), 82-114.

See Emile Durkheim, Suicide: A Study in Sociology, trans. John A. Spaulding & George Simpson (New York: The Free Press, 1951).

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room (New York: Dial Press, 1956), 5.

Edmund Burke, The Writings and Speeches of Edmund Burke, ed. Paul Langford (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), VIII, 332.

Laurence R. Iannaccone, "Sacrifice and Stigma: Reducing Free-Riding in Cults, Communes, and Other Collectives," Journal of Political Economy 100, no. 2 (1992): 271-291.

Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and Moral Order: An Outline for Evangelical Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2nd edn., 2004), 24.

Which are extremely vague, I know; but for the purposes of a Substack, this is as in-depth as I can go.

Fascinating ideas here. Specifically concerning music, my husband and I have exposed our children to so much melody-focused music (as opposed to beat-focused music) that they have the most discerning listening habits of anyone I know. Every now and then I try and turn something on like the Beatles or George Strait (or even Elvis!) and they all say, “please turn that off! We hate it!” It’s amazing how effective our music listening has been on forming their tastes.

As for where the “line” is or what the standard should be when it comes to Christians and music…that is difficult. If we are to seek what is virtuous, lovely and praiseworthy…what does that actually look like??

Icymi, I posted this on a related note but it’s also responding to your article: The McGilchrist insight that has had the largest payout for me, over and over with compounded interest, is that the two hemispheres of the brain can only work together when the right takes the lead. This has so many applications, and something I see written into the structure of reality, the creational ectype to the divine archetype. As Bavinck put it, all created realities aspire to be a triad, as footprints of the triune God. But there are also realities that are fundamentally dyadic, like the brain. The dyadic right and left brain only reflects the Trinity when the right takes the lead, in the dance of right, left, right (see my linked essay below).

Moving this to the subject of morals, generational shifts, and the dialectic of structure vs flexibility, chaos vs rigidity, I believe the solution lies in the relational dance between those poles, a dance that can only be performed by leading with the right brain. As soon as we feel the pull to choose one over the other, either boundaries or fluidity, we are living in the world of the left brain. This might be McGilchrist’s contribution to the 15-20 year generational ping-pong pattern. That isn’t a ping-pong between the right brain and the left brain, but the left brain’s hall of mirrors (McGilchrist’s image) in which each generation remains stuck. (That’s just a theory; the generational morals pattern might exist in cultures that show more hemispheric integration).

https://onceaweek.substack.com/p/a-theology-of-the-brain