What Makes a Discipline "Spiritual"?

A Non-Nerdy Rumination on How to Practice a Wider Range of Disciplines

(NOTE: The following is my best attempt to summarize and simplify my most recent academic paper published through Journal of Spiritual Formation and Soul Care. If you want the more in-depth project along with all the sources I use, see here. Anyways, w/o furtherado...)

Depending on your church tradition, you might have grown some skepticism over certain spiritual disciplines or practices.

For example, many Westerners criticize meditation or breath prayer because they seem a bit too Eastern. Some Pentecostals think praying through pre-written prayers is unspiritual – despite that the Bible contains over 150 of them. Some monastics believe socio-political engagement is sinful. Some Lutherans consider praying for set amounts of time a wasted attempt to earn God’s grace. And, of course, there’s the fear that yoga is demonic.

So, are some groups right and others wrong?

Not exactly. After doing the research, I found that our skepticism/preference has a lot more to do with our historical context, church denomination, and personality type than it does with some people having it all figured out and the rest having it all wrong.

Part of the nature of spiritual disciplines is that they’re fluid. The Bible doesn’t give us a set list. It also doesn’t even give a definition for what a spiritual discipline is.

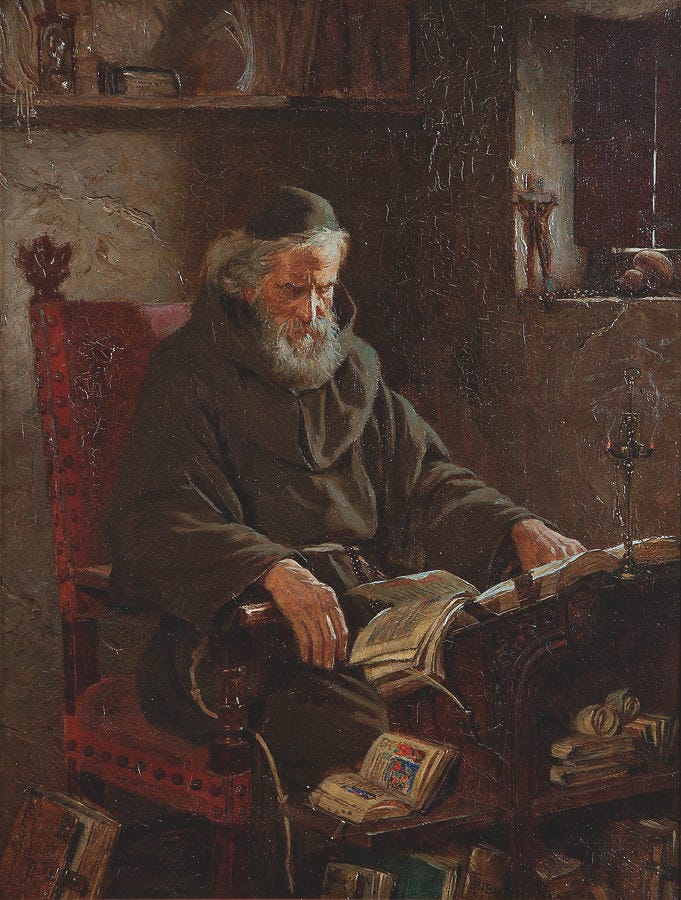

Instead, the Bible offers stories of characters praying, fasting, or entering silence and solitude – but there’s never any “Hey, this is how fasting works at the psycho-spiritual level” explanation provided.

We’re only given context clues. And from those clues, followers of Jesus throughout history have tried to piece together the “why.” And the working theory is that God’s people seem to practice spiritual disciplines in order to grow closer to God and request His power be brought into the here and now.

So, if that’s what spiritual disciplines are for, then shouldn’t any action that leads us to that end count as a spiritual discipline?

Yes, exactly.

But there’s a bunch of roadblocks or misunderstandings that get in the way of us practicing a wider range of disciplines. I came up with 7 (there’s probably more, but 7 is just such a nice round, biblical number).

1. Theological Presentism

The modern West is very ahistorical. Many of us act as though history began in 2010. This makes for “one-generational” models of churches, where styles of worship only go back as far as the head pastor’s living memory.

There might be some things we do better than the pre-reformation church (like reading the Bible in a language the congregation can actually understand, for one). But there’s plenty that we do far worse at (like practicing silence, for another).

But as theologian Gerald Sittser argues, Christian history is a deep well we should always be looking to learn from. Professor Kelly Kapic offers four reasons for why we should meditate on history: (1) it protects us from the idealization of the new, (2) provides context for how to interpret Scripture with wisdom, (3) helps us understand our present experience without treating it as ultimate or ideal, and (4) allows us to see the full history of God’s followers as members of one larger family.

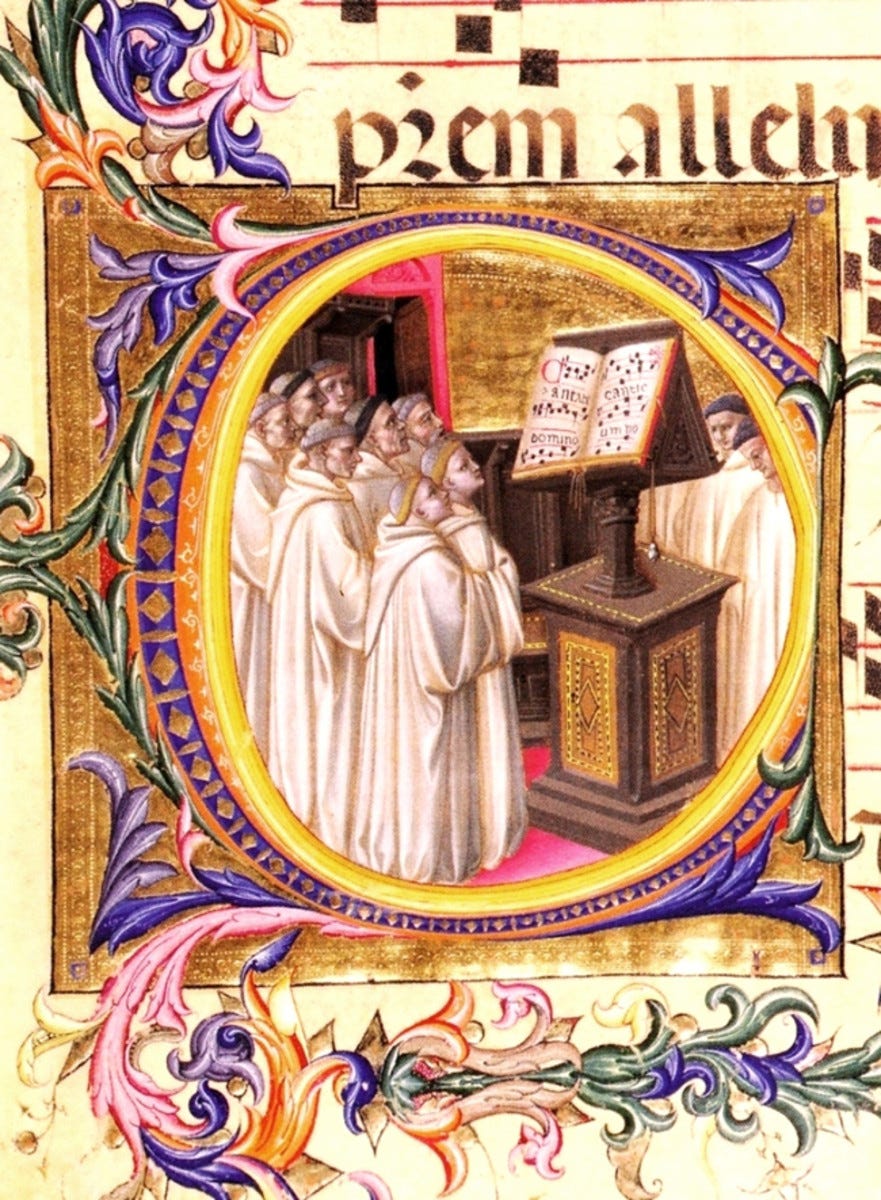

2. Cultural Updating

On the other end, some churches might reject all forms of technological or cultural advancement. It’s wonderful to respect tradition, but this can easily get taken too far and get distracting. Jesus was born in a specific point in history, but His presence isn’t locked in that single moment. The same could be said about church practices. While history is incredibly important, we don’t need to vilify radio-friendly worship styles in lieu of Gregorian chant.

3. Semantic Confusions

There are many instances where people criticize certain practices simply because they had an unfamiliar title. For example, some people who critique “contemplation” are also adamant about practicing “beholding” – which is the practice of sitting in the presence of God and gazing at His beauty. This borders on the exact definition of contemplation. A surprising number of similar confusions have happened across time and space. Just because a practice is described in a way that’s unfamiliar doesn’t mean it’s heresy.

4. Sacred-Secular Divide

It’s pretty typical to divide up your life into sacred categories (like church, worship, prayer, etcetera) and secular categories (like listening to non-worship music, watching a Glen Powell movie, mowing the lawn, etcetera). But this is only a modern idea. Most of church history knew that all of life was spiritual – not just the churchy “spiritual” sounding things.

For example, many Westerners tend to think of a fast as spiritual and a meal as non-spiritual even though there’s no difference in their amount of “spiritual.” Catholics have been in the know about this for awhile, which is why their calendar has both “fast days” and “feast days.”

Everything is spiritual. The point is not to fill our entire schedule with “spiritual” sounding things but to submit everything that’s already in our schedule – from laundry to parenting to driving to work – to the glory of God.

5. Personality Types

While the Enneagram and Myers-Briggs tests can be helpful, neither of these personality tests have any rooting in actual psychology. In academic circles, they use the Big Five (Extroversion, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, Agreeableness, and Openness).

However you place on these five traits essentially decides the kind of things you’ll naturally like to do. For example, if you’re higher on extroversion, you’re more likely to drift toward disciplines like group worship or celebration. If you’re low on conscientiousness, you’re more likely to take risks, which makes you more likely to pursue social justice or give away money generously. This is important to understand because sometimes people will criticize certain practices simply because they don’t line up with their personality preferences.

6. Learning Styles & Discomfort Zones

Recent research has found that learning styles are essentially a myth. For example, studies have shown that students who say they prefer auditory learning actually don’t learn very well in auditory educational environments. As the research shows, students often learn best when they go against their preferred learning style. Basically, the best kind of learning happens in “discomfort zones.”

The same rule applies for spiritual disciplines. If you’re looking to grow, don’t stick to your usual rhythms. Break out of your mold and personality style and get uncomfortable.

7. Denominational Jingoism

“Jingoism” is a patriotism toward a nation or organization so powerful that it disregards anything unnatural to the nation/organization. This is exactly what many people do with their denomination or home church. A lot of skepticism gets thrown toward practices simply because they’re foreign, not because they’re actually Biblically heretical.

When you limit your experience to one single denomination, you tend to miss out on other streams of the faith and all they have to offer. This isn’t necessarily the worst thing: everyone has a denomination of choice. But the problem comes when we can’t respect other traditions and practices and insist that everyone must follow our exact model or else they’re not “real” Christians.

The danger in rejecting spiritual diversity is that it causes our spirituality to get a little stale.

uses the analogy of a potluck:“Indeed, nothing could make a potluck worse than when everyone brings the same dish. A good potluck is a potluck where everyone brings their best dish. By analogy, each tradition in the church has a gift to bear. But we also have something to receive from others...It is only in seeing this rich feast that we can appreciate our own dishes and the dish of others.”

Richard Foster, the godfather of modern spiritual formation, depicts the different expressions of Christianity as distinct streams of living water flowing from the same Divine origin. Whether we use the word picture of a deep well, streams, or a potluck, the point is the same: our inability to respect other traditions makes us weaker while our diversities make us stronger.

Drafting the Theory

Anyways, after all that groundwork, this is the definition of spiritual disciplines that I came up with that also passed the peer-review process:

A spiritual discipline is any temporal action that leads us toward the transforming presence of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Anything that does not meet that simple criterion – or leads an individual or community away from that presence of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – should be discounted.

And, in the event that there’s a gray area, an individual should bring it before their community for discernment.

To end, most of this could be summarized in this wisdom from Philip Sheldrake:

“The gift and task of Christian life in the Spirit is to cultivate, nurture and sustain the variety of the manifestations of the magnitude of God’s love in all forms of expressivity and creativity.”

Thank you for a helpful post, and congratulations on the publication!

Roadblocks 5 and 6 seem especially pertinent for my small group and church. I've mentioned dispositions in general when teaching on the disciplines, but never so specifically as to try to relate specific traits to specific disciplines. Is there a source you could share on this? I'm interested in reading more.

It seems like roadblocks 6 and 7 are likely to be heavily bolstered the environment of cultural/consumer Christianity. Actually, I think all seven points you mentioned may be closely related to that plague.

One thing I've also observed is the tendency to view "discipline" negatively. To teach against this, I have gone so far as to call them "Spiritual opportunities", as they are time-honored opportunities in which Christians may embrace the will of God for their sanctification.

This is really helpful thank you. Your definition gives permission to bring creative with exploring new forms of disciplines as well as diving deep into ancient ones.