Gaining Time Through Wasting It

Meritocratic Burnout, Deliberate Play, and Meticulously Regimented Fun

1. Surprised by Play

Last year, I honestly thought I contracted mono. In reality, I was just getting older and busier.

2.5 years of full-time work, full-time school, various writing projects, volunteer work, and navigating the first years of marriage was catching up to me. My free time was zero, recreation non-existent, and mental health dismal.

I grew up in a world that taught me I had two options: (1) work yourself to the bone to get ahead (2) or resign into comfortable mediocrity.

Basically, either tough it out in a perpetual state of burnout or check out from climbing the social ladder altogether.

At the time, I was trying to pull off the former.

Ironically, a lot of my writing projects were spiritual formation related. And a huge component of spiritual formation is the spiritual disciplines – little actions and rituals that put us in position to receive transformation from the Spirit.1 Which include things like fasting, prayer, and Sabbath.

So before I launched into this 2.5-year sprint of busyness, I made a rule that no matter how busy I got, I’d maintain boundaries for a 24-hour weekly Sabbath.

Still, I was exhausted; one day of rest wasn’t offsetting the six days of scurrying from task to task like my brain was extinguishing six fires at once.

So then I got on the Ruthless Elimination of Hurry bandwagon – which might be to Gen Z what Purpose Driven Life or Crazy Love was to Gen X-ers – and found more ways to slow down, carve out silence and solitude, and make amends with my overextended schedule.

Which helped – a lot – but something still felt off.

Then last winter, I woke up on New Year’s Day feeling better than I’d felt in months – an enigmatic occurrence for anyone’s NYE morning after. Not only did I feel restored, but I logged in two straight hours of writing “flow.”2 I got so much done so fast that I felt satisfied shutting the laptop early and my mind never wandered back the rest of the day.

Which was so out of character that my wife and I had to investigate. We hit the drawing board and drafted up a few isolated variables from the night before:

Celebration

Laughter

Messing around with friends

It might sound silly, but I think my overexhaustion was less due to an absence of rest than an absence of fun.

Eliminating hurry is crucial, but I think true rest is about more than not working. I was craving fun, connection, and celebration at a soul-level.

So, as a writer, researcher, and nerd, I wanted to figure out if there was anything to this: is “wasting” time on fun not really a waste?

2. 007, Meritocracy, Burnout Society

If you watch the end of any old James Bond movie (pre-Daniel Craig) you’ll find 007 finally getting a chance to relax after saving the world, resting in carefree romance with the Bond Girl. But as the movies progressed, they got darker and darker until the newer ones started doing away with that ritual altogether.

Whereas the older films reward Bond with a well-deserved break, the newer films just reward him with more work. At the end of Skyfall, after Bond almost dies multiple times and attends his mother figure’s funeral, he meets with M who asks, “Ready to get back to work?”

“With pleasure,” Bond replies. Credits roll.3

Any human in his position would be on the brink of emotional death.

But our culture valorizes this kind of no-nonsense behavior.

At some point, we started interpreting a protagonist’s need for celebration or reprieve as weakness rather than reward.

So I asked a friend about this aversion to recreation, and he said if I wanted to know the “why,” I should probably pick up a few books by the philosopher Byung-Chul Han.

South Korean born German social theorist Byung-Chul Han is one of the most influential living philosophers (and in 2021, he came out as a Catholic, so naturally Christians have rushed to claim him as their own).4

His whole bibliography builds upon a diagnosis of the modern condition: we’re overtired, exhausted, and fatigued. Which is unsurprising, of course.

But the surprising part, I found, is that we’re not burning out because of some external authority that’s telling us we have to work 24/7, but because we make ourselves work 24/7.

Which is a newer phenomenon – and part of the packaged deal of living in a meritocratic society.

A meritocracy is a societal system where people get ahead based on hard work, talent, or ability as opposed to lineage or luck. You know, the American dream. Most Western nations are now (supposedly) meritocratic.5

Meritocracy was designed as a more civil evolution from aristocracy, which is a society governed by privileged elites or royal families with a heavy emphasis on class division and social hierarchy.

And even though meritocracy is better than aristocracy in many ways, it also comes with the side effect of burnout.

In aristocracy, people didn’t work because they wanted to be “go-getters.” They picked up their trades so they could take part in society or not ruffle the aristocracy’s feathers.

However, there’s not much incentive to work beyond what’s required because there’s no hope of ascending the social ladder. Status is assigned at birth.

But once aristocracy evolved into meritocracy (see 1776), your birth status started mattering far less.

This is where the idea of upward social mobility comes into the picture.6

Your social position finally depended less on family of origin than your ability to hustle to the upper echelons.

But, sadly, the sheer possibility of upward social mobility is a gift that comes with the thorn of intrinsic pressures and exhaustion.

It also meant that when people felt frustrated with their social position, they no longer placed the blame on the system itself (i.e., the corruption of the royal family).

In meritocracy, the only person to blame for your lack of success is yourself (i.e., your lack of talent or hard work).

This is why Han doesn’t call our system a meritocracy but a “burnout society.”7

Burnout society doesn’t create external rules (as in, “It is a legal requirement that you do this”). It builds incentive structures that self-motivate people to work through ‘intrinsic motivation’ (as in, all those self-helpish platitudes like, “You can do this. Don’t let them see you fail. No days off. You are enough”).8

Which is the exact messaging that floods everything from our Instagram feeds to commercials to fitness apps to podcasts. In burnout society, even though we’re in charge of our own schedules, we still somehow make them look like this:

Wake up, caffeinate, meditate, work out, get the family out the door, yell at cars on the way to work, endure a resting heart rate of 156 bpm for eight to ten hours, resign to exhausted contempt toward traffic on the way home, cook, clean, online shop, keep up with the latest trending Netflix show to not fall behind, get frustrated at yourself for not reading that book you meant to read or finishing that project you wanted to have done last week or shaving those five pounds you wanted off last month, crash with a Benadryl/wine/Ambien, restart.

This kind of lifestyle essentially guarantees more frustration than fun. The journalist Anne Helen Peterson sums it up:

Why can’t I get this mundane stuff done? Because I’m burned out. Why am I burned out? Because I’ve internalized the idea that I should be working all the time. Why have I internalized that idea? Because everything and everyone in my life has reinforced it—explicitly and implicitly—since I was young. Life has always been hard, but many are unequipped to deal with the particular ways in which it’s become hard for us.9

We’re exhausted because we feel like we need to be exhausted because exhausted people are the only “successful” kind of people. And this mindset, of course, cuts out all play from the daily schedule.

· All work and no play has just become the normalized way to stay afloat.

So, Han’s points are pretty convincing. In our world, the crown isn’t to blame; I’m the progenitor of my own burnout. Sometimes I’m just plain anxious that recreation will cause me to fail or get behind.

This is a society-level reason for resisting play. But there’s also quite a few psychological reasons.

3. Anxious Gen, Negativity Bias, Bueller

While many moderns belong to the “Burnout Generation,”10 psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls my generation the “Anxious Generation.”11

We were the first group of kids to have Twitter and Instagram before puberty. Throw in helicopter parenting, the 24/7 fear porn news cycle, and “safetyism”12 – the idea that physical and mental safety is the highest importance – and you get a generation that’s raised to expect the worst, all the time, from everywhere.

Which, as I came to find out, already happened to be a pretty big feature of the human brain.

Psychologists find we have a much stronger bend toward negativity than positivity.13

It only takes 8-10 seconds for a negative experience to ingrain in our long-term memory, while it takes 14-20 seconds of deliberate attention for a joyful experience to sink in.14

This “negativity bias”15 is also why the worst thing that happens to us all day superimposes itself on our consciousness as we’re trying to fall asleep; even if we’ve received a pile of compliments, it’s usually the single insult that glues to our mind’s eye.

Our attention wires toward the bad. If we don’t, as Ferris Bueller pointed out, stop to look around every once in a while, we’ll quite literally miss the good.

This is another angle to our aversion to fun: we’re so conditioned to expect the worst that letting loose can feel irresponsible. Natural instinct pushes us to stay alert, put our guards up – and celebration or fun or deliberate playfulness can sometimes just make us feel vaguely guilty.

Take this for example: have you thrown more parties in the past year or attended more funerals? Do you spend more time in gratitude for what you’ve accomplished or frustration for not accomplishing enough? Maybe you’re an exception, but the odds are, your answer was the latter in both scenarios.

Which leads us to a tendency common in Christian circles: when negativity is not only tolerated but valorized.

4. The Christian Coalition Against Celebration

Lots of us modern Christians – myself included – buy into an illusion that it’s our divine responsibility to be uber serious and unplayful in every situation. We legitimately have less fun than Jesus.

Some circles have such disdain toward the prosperity gospel that they over-correct and adopt the poverty gospel – where misery and suffering are the only way to holiness and fun is for heathens.

John Wesley might’ve shared this outlook. When he ran Kingswood school, they met every day except Sunday, and he didn’t permit any play during school hours on the principle that “he that plays when he is a child will play when he is a man.”16

Or take Cappadocian Father Basil of Caesarea, who once said, “The Christian…ought not to indulge in jesting; he ought not to laugh or even to suffer laugh makers.”17

You might even find this mindset in The Rule of Saint Benedict, where Saint B. named “restraint against laughter” as the tenth virtue to acquire if one wished to ascend his famous ladder to humility.18

This mentality is, of course, super flawed. Being a buzzkill isn’t a fruit of the Spirit, and God never asks us to be more serious than He is.

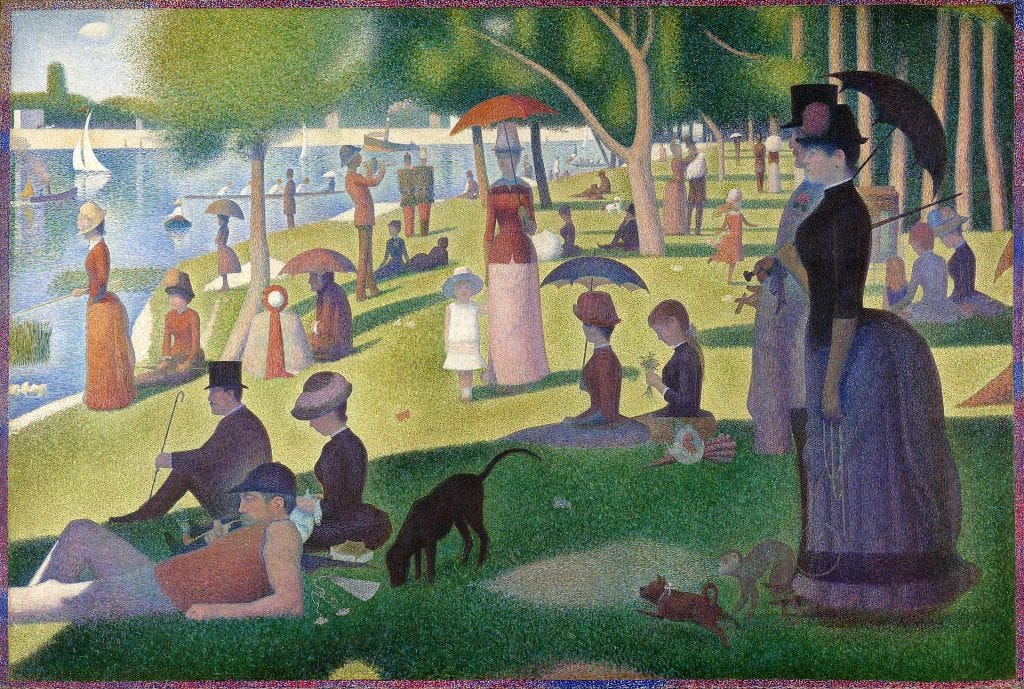

This is why spiritual formation guru Richard Foster called celebration a spiritual discipline.19 Sometimes it can feel like having a party or celebrating good news is a waste of time – something only the lazy can manage. In actuality, it requires more discipline, more focus, and more intentionality to celebrate than to lament.

“How can we celebrate when there’s so much pain in the world?” is a question that has never not been applicable. There always has been suffering and always will be suffering in this world. If we work off this logic, celebration would never happen.

There’s this great scene from The Chosen that directly winks at our obsession with pragmatism.

After Jesus calls the disciples, the first thing he announces is that they’re going to a wedding. The camera lingers, and the disciples look confused.

It’s playing off the sudden sequence of events in John’s Gospel: Jesus comes into the world, lives 30 years in obscurity, gets baptized, receives the Holy Spirit, calls His disciples, and then the narrative jumps right into a wedding in Cana.

Jesus’ messianic ministry only begins after receiving the Spirit. And from that point on, it’s technically crunch time – only three years until the cross.

In our Western efficiency mindset, it’d make more sense to get the weddings, feasts, and parties out of the way in those 30 years pre-baptism so those last three could just be a grind.

But we have the type of God who considers it a primary importance to attend a wedding even when there’s a deadline, hungry people to feed, and sick to heal. And since sin wasn’t a thing for Jesus, we can be confident that it’s not selfish or lazy to celebrate even when there’s a mountain of work left to do.

As the writer of Ecclesiastes says, “For everything there is a season…There is a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance.”

There’s a time for every aspect of the human experience. We shouldn’t just pick and choose the ones that seem efficient. We have just as much responsibility to give thanks as to lament. And we have just as much need to take Sabbath and say “no” to extra work as we do to play games or gather around tables with friends laughing so hard that we almost choke on our food.

As C.S. Lewis put it, “It is a Christian duty, as you know, for everyone to be as happy as he can.”20 Playing, celebrating, throwing parties for our neighborhood should just be a natural part of our kerygma (our proclamation of Christ crucified). The more joyful we are, the more magnetic Christ appears to others.

And strangely enough, it’s also been well documented that the more time we make for fun, play, and celebration, the more it enhances relationships, creativity, and experience at the workplace.

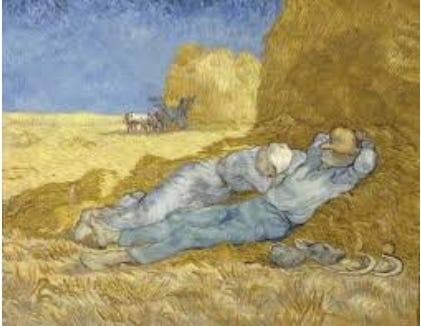

5. Take More Breaks, Get More Done

Multiple studies have shown that productivity and creativity plummet without rhythms of recreation.21 Basically, we get bored or stressed when we don’t make enough margin for fun.

But when researchers added periodic breaks between work for “deliberate play”22 – social science slang for intentional fun or celebration – it helped sustain passion, reduce fatigue, and incentivize fresh ideas.

Which might explain why, on National Hangover Day, I woke up excited, restored, and flooded with creative ideas.

Logically, it makes sense that more work equals more productivity. But apparently, it doesn’t.

One study found that researchers who put in 20 hours a week at their lab were more productive, wrote more studies, and published more articles than a group of researchers at the same lab who clocked in thirty-five weekly hours.23

There’s even a good amount of research to support that working less while retaining the same salary can make the whole company more productive and profitable.24

Sabbath is great, slowing down is great, eliminating hurry is great – but we also need play.25 God created too many incredible, intriguing, humorous, and downright joyful facets of the universe for us to assume that He was still hoping for us to be in productivity mode 24/7. Maybe rhythms of play should be just as regimented as our rhythms of prayer, morning coffee, or workout routines.

This is the bottom line: if we don’t make room for deliberate play, we’ll burn out under the weight of seriousness we’ve forced upon our own shoulders.

Personally, I fought my own burnout by carving out more time for “wasting” time with friends and family. Even when I’m exhausted and staying in seems rational, I remind myself that laughter and connection is probably better medicine than lying comatose on a couch, scrolling on my phone. I call it “meticulously regimented fun,” and so far I’m the only one who finds that funny.

I also put the meritocratic, self-helpish pressures to bed. I want to be great; I want to create mind-blowing work; I want to be the best me I can be; but I only want to strive for that within the confines of my natural human limitations. So, I made it a rule to only work on my writing until my joy valves are dry for the day; when it becomes a slog, labored, or distressing, it means it’s time to wait until tomorrow to start again.

I can accomplish whatever I have the time and energy to accomplish, but no matter how much Celcius or B-vitamins I consume, I can’t manufacture more productivity – at least, not more good productivity. And when I’m past my limit, I don’t switch to other forms of working like catching up on house projects or reading heady books. I throw on a comedy podcast or play a boardgame or text fake The Onion headlines back and forth with my best friend or go on a walk with my wife, guilt-free.

Elon Musk once said some shame-inducing line that spread across the hustle culture interwebs that went something like: “No one ever changed the world on 40 hours a week.”26

Well, plenty of people have. And they’ve even had fun while doing it.

By “wasting” some of our time, we use all our time better.

Definition inspired by Dallas Willard, The Spirit of the Disciplines (San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins, 1988).

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper Perennial, 1991).

The philosopher Byung-Chul Han uses this analogy in his book Psychopolitics.

See Byung-Chul Han, “The Tiredness Virus,” The Nation, April 12, 2021, https://www.thenation.com/article/society/pandemic-burnout-society/.

Though contemporary meritocracy is so remarkably flawed that many argue it may as well be called a neo-artistocracy. See Michael J. Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit: Can We Find the Common Good? (New York: Picador, 2021); see also Daniel Markovitz, The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite (New York: Penguin Books, 2020).

Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society, trans. Daniel Steuer (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015).

‘Intrinsic motivation’ is a psychological concept that denotes a variety of motivation that is self-propelling and ambitious in and of itself. Paul Baard et al., “Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of Performance and Well-Being in Two Work Settings,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34 no. 10 (2004): 2045-2068. This point also correlates with Alasdair MacIntyre’s exposition on the emotive self: “The specifically modern self…finds no limits set to that on which it may pass judgment, for such limits could only derive from rational criteria for evaluation and ... the [modern] self lacks any such criteria. Everything may be criticized from whatever standpoint the self has adopted, including the self's choice of standpoint to adopt.” Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (South Bend, IN: Notre Dame University Press, 1985), 31-32.

Anne Helen Peterson, Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation (New York: Dey Street Books, 2020).

Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness (New York: Penguin Press, 2024).

Jonathan Haidt &

, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (New York: Penguin, 2018).See Roy Baumeister’s The Power of Bad: How the Negativity Effect Rules Us and How We Can Rule It (New York: Penguin, 2019),

Tea Sindbæk Andersen & Jessica Ortner, “Introduction: Memories of Joy,” Memory Studies, 12 no. 1 (2019), 5-10; Megan E. Speer & Mauricio R. Delgado, “Reminiscing About Positive Memories Buffers Acute Stress Responses,” Natural Human Behavior 1 (2017): 0093; Mauricio Delgado, et. al., “Nostalgia Rewards the Brain,” Nature 515 no. 11 (2014).

Amrisha Vaish, et al. “Not All Emotions Created Equal: The Negativity Bias in Social-Emotional Development,” Psychological Bulletin 134 no. 3 (2008): 383-403.

The Works of John Wesley (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1958), XIII, 285.

Basil of Caesarea, Letter 22: On the Perfection of the Life of Solitaries, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3202022.htm.

St. Benedict, The Rule of St. Benedict: In Latin and English with Notes (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1981), 7, 59-61.

See Richard Foster’s Celebration of Discipline.

C.S. Lewis, via Sheldon Vanauken, A Severe Mercy: A Story of Faith, Family, and Triumph (New York: HarperOne, 2011), 189.

Patricia Albulescu, Irina Macsinga, Andrei Rusu, Coralia Sulea, Alexandra Bodnaru, and Bogdan Tudor Tulbure, “‘Give Me a Break!' A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Efficacy of Micro-Breaks for Increasing Well-being and Performance,” PLoS ONE 17 no. 8 (2022): e0272460.

Erin C. Westgate and Timothy D. Wilson, “Boring Thoughts and Bored Minds: The MAC Model of Boredom and Cognitive Engagement," Psychological Review 125 no. 5 (2018): 689-713; A. Mohammed Abubakar, Hamed Reza Pouraghdam, Elaheh Behravesh, and Huda A. Megeithi, “Burnout or Boreout: A Meta Analytic Review and Synthesis of Burnout and Boreout Literature in Hospitality and Tourism,” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 31 no. 8 (2022): 458-505.

This study appears in

, Scarcity Brain: Fix Your Craving Mindset and Rewire Your Habits to Thrive with Enough (New York: Random House, 2023), 256.Gianluca Voglino, et al. “How the Reduction of Working Hours Could Influence Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Published Studies,” BMJ Open vol. 12 no. 4 (2022): e051131; John H. Pencavel, (2015), “The Productivity of Working Hours”, Economic Journal 125 no. 589 (2015): 2052-2076.

Laura M. Gurge and Kaitlin Woolley, “Working During Non-Standard Work Time Undermines Intrinsic Motivation,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 170, no. 1 (2022): 104134; Adam M. Grant, Justin M. Berg, and Daniel M. Cable, “Job Titles as Identity Badges: How Self-Reflective Titles Can Reduce Emotional Exhaustion,” Academy of Management Journal 57 no. 4 (2014): 1201-1225.

Elon Musk said this in some interview. It’s out there on the interwebs. I took nyquil last night. I’m too tired to look up exactly where. It might be so ingrained in social stock knowledge that I can get away with not citing it. But then again, I took nyquil last night.

I think this is one of the aspects of "becoming like a little child" as Jesus shockingly asked all of us to be. Children play *so naturally* and have fun without restraint or the need to somehow make it productive. Children are our best examples of joyful play; we just have to set aside our serious faces and join them every once in a while.

Ha, I only started following you the other day but you suddenly pull this out the bag. I have just started my own substack which is all focused around what I wrote my Theology Thesis about: how play can help our spirituality. So I read this with interest, thanks very much.