Grace Might Have Strings Attached (and Why That’s Not a Bad Thing)

Patronage, John Barclay, and How Strings Make Grace Even Better

An audio voiceover/commentary is available for paid subscribers here!

1. A Rumpus About Strings or (Lack Thereof)

In one of the more famous anecdotes about C.S. Lewis, he strolled into a roundtable discussion among some of the greatest minds in the field of comparative religions. They seemed frozen on a question, so Lewis asked, “What’s the rumpus?” (which is the best possible noun Lewis could’ve chosen). They were brainstorming what made Christianity unique among world religions but coming up short. Then Lewis responded, “Oh, that’s easy. It’s grace.”

This left the experts immediately satisfied. They deliberated that grace was unique in that it was a free gift with “no strings attached.”1

This anecdote has all the elements of a great story, but one notable issue: it’s not true.

C.S. Lewis did actually walk into this roundtable discussion and the experts did agree on his response based on the idea that grace didn’t have strings attached. All that’s true. The untrue part was actually just the last few words: the “no strings attached” part.2

In the world behind the Bible, grace always had strings attached.3 That’s actually part of what grace meant — that it would bind two parties into a relationship of mutual reciprocity.4 Grace that’s free from expectations didn’t enter the Western imagination until after the Reformation.5

And this basic idea of reciprocity is actually pretty common among world religions (i.e., sacrifice this calf to Baal, receive Baal’s favor). So in reality, grace isn’t what makes Christianity unique.

Rather, what makes Christianity unique is its degree of grace. It usurps all other forms of grace because the God who offers it offered Himself first as a sacrifice — and continues to keep the gift on the table even if we recoil from it.

2. Some Background on the Patronage System

The debate around the “no strings attached” view of grace crescendoed around the release of early church historian John Barclay’s book “Paul and the Gift.”

Here’s a sparknotes summary: a 1st century Christian would’ve understood charis (usually translated as “grace”) as a “gift.”6

But it’s not the kind of one-time gift you and I think of today (i.e., a free gift that you give without expecting anything in return).7 Rather, they would’ve seen it as a symbol within the “patronage system.”

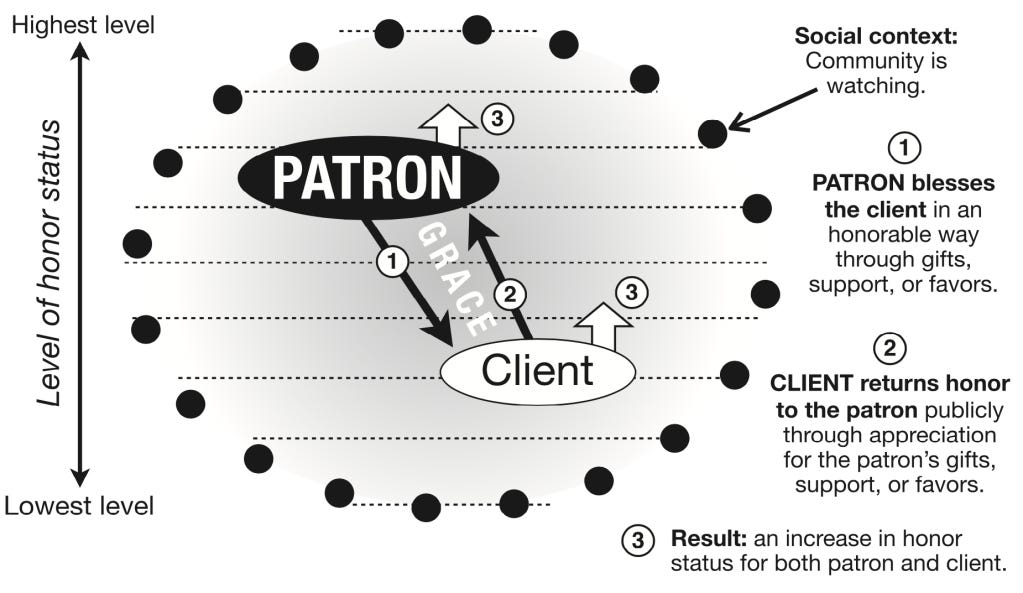

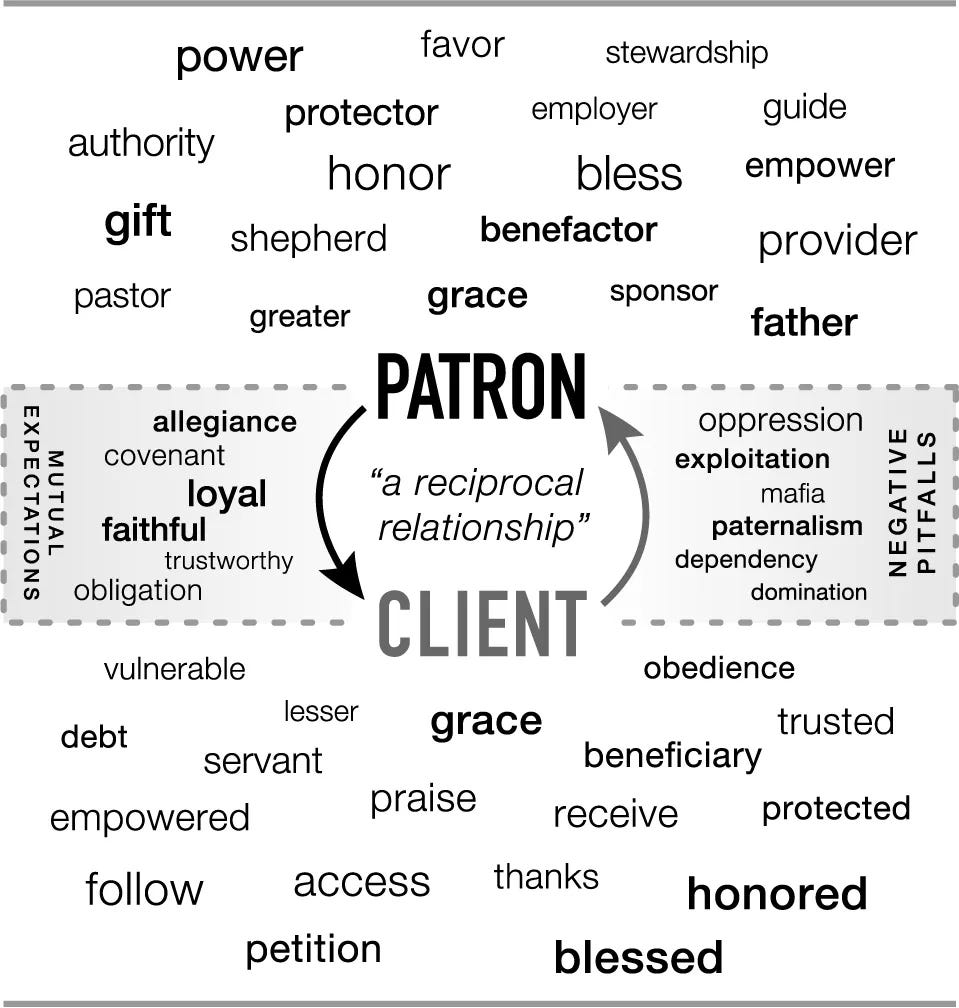

In the world backgrounding the New Testament, when someone needed something the public marketplace couldn’t supply, they would seek out a patron – typically a wealthy or powerful figure in their city – and ask them for a charis, usually in the form of some kind of service or monetary sum.

If a patron has “favor” on a client, the client is then expected to pay them back – but their payback isn’t a tit-for-tat, returning an equal favor kind of thing. It’s more so about establishing an ongoing relationship where a patron sustains their client’s needs in exchange for gratitude, allegiance, and loyalty. Essentially, if you had to boil it down, the main expectation was that a client would publicly magnify the greatness of their patron’s name.

In modern terms, we might call it a you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours relationship.8 By accepting one favor, it locked you into a limitless exchange of favors. Like Sophocles wrote in Ajax, “one favor always begets another.”9

Despite the inequality between a patron and a client, they still referred to one another as “friends” and their dynamic as “friendship.” In fact, on Caesar’s coins, which had his own likeness imprinted on it (Matt.22:20-21), there was another inscription that said, “ΦΙΛΟΚΑΙΣΑΡ,” which means “friend of Caesar.” It was a way of saying that since this money came from Caesar, however indirectly, you owed him loyalty.10

However, patronage was often abused in the 1st century – with some patrons acting like Tony Soprano mafiosos or manipulating gifts to win political support.11

But when it was used well, patronage was like a leg-up program where the wealthy could assist those who couldn’t pay off their debts. Because of the way it performed social welfare apart from governmental assistance, Seneca called it the “practice that constitutes the chief bond of human society.”12

Which brings us to the most crucial aspect of patronage: the client’s willingness to abide by the strings attached. If the client doesn’t respond with gratitude, the system falls apart. As Seneca explained, “Ingratitude is something to be avoided in itself because there is nothing that so effectually disrupts and destroys the harmony of the human race as this vice.”13 There were few faster ways to lose your honor (the 1st century equivalent of social status or reputation) than refusing to honor the giver of a gift.14

Ok, that was a lot of me writing. There will also be writing hereafter, but here’s some breathing space in the form of this picture illustrating patronage:

There were still words in that pic, so here’s another pic, but with no words:

Ok back to the strictly syntax. Let’s look at how grace pops up in the New Testament.

3. Patronage in the NT

The patronage system was so deeply embedded into Greco-Roman culture that there was never need to put it into law.15 That would’ve been like the U.S. legislating the celebration of children’s birthdays – there’s no need to enforce it; it’s just something people do.

This embeddedness is why scholars have been seriously reevaluating charis. NT grace probably carried more connotations than a present bought for one of those non-enforced child birthday parties.

Paul’s letter to Philemon might contain the strongest example of patronage. In what many consider one of the most passive-aggressive epistles, Paul affirms Philemon – a wealthy patron who financed many early Christian operations – for his past generosity (v. 4-7) before moving on to the big ask.

Paul says he’s returning Onesimus, Philemon’s escaped slave,16 but hoping that Philemon would receive Onesimus no longer as a slave but as an equal (v. 17-20): “Confident of your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I say” (v. 21).

This almost reads like a passive-aggressive smirk, but that’s because we’re missing the undercurrents of patronage. Even though Paul could’ve technically commanded Philemon to do what he wanted (v. 8), Paul chooses to appeal to Philemon’s good character.

This is exactly how a patron might address a client or vice versa — subtly noting the desired outcome while reminding them of their past generosity, almost as if priming their memory toward their history of favors. And as NT scholar David deSilva notes, the public reading of this letter would’ve pinned Philemon into a corner – putting his reputation on the line in front of the whole church if he were to refuse.17

So even though many have critiqued Paul’s letter as not-anti-slavery-enough, in reality, its foremost goal was to acquire this slave’s freedom, and its sugar-coated language was tactically designed to yield that exact result.

Beyond the human-to-human implications, Barclay offers two main ways patronage reframes God’s charis:

(1) it shows how God generously and perpetually offers Himself before we’ve made any moves toward Him;

(2) it reveals how this gift anticipates a response from us.18

The second point doesn’t imply that we need to pay God back – 1st century clients had no feasible way to get “even” with their patrons either.

The charis of God is still “free” (Rom. 3:24). But so was every other charis. And they were free precisely because a patron anticipated their client would honor them in return. We can even see grace’s circular motions in Ephesians 2:8-10:

For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.

We don’t receive this gift by good works but for good works. There’s an in-built expectation that we’ll walk in whatever God’s prepared for us.

Call this a string or an expectation or God meticulously controlling your actions via predestination, but it’s there. However, Barclay and others stress that these strings aren’t malicious or coercive; they’re more of a hopeful mechanism toward latching us into an ongoing, life-giving relationship.19

And this relationship, like Martin Luther pointed out, is the most uneven relationship we could fathom.20 Our wildest imaginations could never produce anything that could allow us to “get even” with God.

But even if we could, our efforts would miss the point. God isn’t interested in accumulating interest through our works. This would imply that God “needs” us to glorify Him. But He doesn’t, because there’s no way to enhance His goodness; it’s already perfect, whole, complete. So these strings are less God’s way of hoarding our affections than inviting every creature to behold and partake in the joy of His goodness.21

Which are perhaps the least burdensome strings fathomable. Throw in the fact that living in alignment and gratitude toward God is the best possible way humans could inhabit life, it morphs from a burden into a “pearl of great price” that overshadows all opportunity costs (Matt. 11:28-29; 13:45-46). Like Dallas Willard put it, when we tally the costs of discipleship alongside the costs of non-discipleship, we see that the latter’s cost far outweighs the former’s.22

Yet it’s not just that these strings don’t cost much. They’re an entirely positive force. The gift is what draws us into relationship with God, and our willingness to abide allows us to experience the fullness of the gift, perpetually.

4. The Joy of Response

Yet, for some, all this might come off as coercive. Americans often think of “unrequited love” as love’s purest form. Rom-coms and shows like How I Met Your Mother describe this one-way love as it’s love’s perfect essence. But this is totally misguided — both in terms of our relationship with humans and God.

The entire narrative of the Bible is about a God seeking reciprocal love from His creatures. Unrequited love is romantic in theory but awful in practice. Can a marriage really thrive if one abides by the boundaries that the other excuses themselves from?

Yes, God’s love doesn’t need our requiting, as in Hosea and Gomer. But no sensible person really believes that Hosea and Gomer are relationship goals. Heathy relationships are mutual, cooperative partnerships.

Even further, it’s a tad funny that modern Westerners are so quick to call giving for the sake of receiving manipulative, because we still do this all the time.23

Consider every fraternity’s marketing: “You’ll get amazing job connections! Remember, it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” Or just think about how everyone reacts when the family says, “Let’s not do gifts this year” and one member breaks the pact. The resulting groans originate from the unspoken but nonetheless understood standards of reciprocity.

Deny it all we might, reciprocity is still everywhere – we’re just way more subtle about it. And just like Greco-Romans, studies show we still feel disgust when there’s no “thank you” given in return for something that deserves gratitude.24

We might not take it as far as Seneca, who wrote, “homicides, tyrants, thieves, adulterers, robbers, sacrilegious men, and traitors there will always be; but worse than all of these is the crime of ingratitude,”25 but we still take gratitude seriously.

Interestingly, even apart from the patronage stuff, many theologians also arrived at similar conclusions.

Thomas Aquinas considered ingratitude a special sin because it so boldly overlooks the blessings God’s planted in and around us.26

Jonathan Edwards described ingratitude like an outward manifestation of inward moral corruption.27

Even Martin Luther was emphatic that neglecting gratitude toward God’s gift was self-idolatry.28

It’s also a key part of Satan’s neurosis in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Even though Satan understands that he owes God thanks, he can’t bear to acknowledge it (PL 4:46-57). To admit gratefulness would imply God’s superiority and his own inferiority. Even though Satan realizes that gratitude is “the easiest recompense” in light of all God’s done, he still rejects the bare minimum, “refusing to give God even a fraction of what God is due.”29

Yet out of all the examples I found, Karl Barth had the most illuminating explanation:

Charis always demands the answer of eucharistia [thanksgiving]. Grace and gratitude belong together like heaven and earth. Grace evokes gratitude like the voice an echo. Gratitude follows grace like thunder lightning. Not by virtue of any necessity of the concepts as such. But we are speaking of the grace of the God who is God for man, and of the gratitude of man as his response to this grace…Radically and basically all sin is simply ingratitude—man’s refusal of the one but necessary thing which is proper to and is required of him with whom God has graciously entered into covenant…gratitude is the complement which man must necessarily fulfill.30

Now, whether responding to God’s grace is a prerequisite for justification or just a component of sanctification is beyond my pay grade.31 But if these are the questions we’re asking, we may be missing the point. This charis is so unique, surprising, and gorgeous that coming into an understanding of it should naturally result in praise.

What makes the Trinitarian God’s gift surprising and unique is that it’s given regardless of worth, merit, or restraint.32 The “insurmountable gift” (2 Cor. 9:15) bulldozes prior understandings of patronage in that it continually makes itself available to those who commit the chief sin of rejecting it (Luke 15:11-32).

Further, a right-minded patron would never (ever) sacrifice himself for a client; in fact, patrons often gave gifts so that a client would make sacrifices for them – not vice versa. So for Jesus to not only offer a gift that exceeds our minds’ capacity for comprehension, but to also lay His life down for his clients/friends (Jn.15:13-15), was and is and always will be an absolute revolution.

5. Sorry, that was a lot. And there’s more. This is Reality Theology, not biblical theology, so I have to connect this to other research.

You might be thinking so what? That’s a great question. For me personally, I think the best answer to the so what? is that reciprocity inspires a unique and beautiful kind of motivation – both in our interactions with God and others.

As anyone who’s mentored high schoolers or college kids can attest, telling them “Do this, don’t do that,” is almost guaranteed to backfire. And yet this authoritarian mentality is still the go-to for many organizations – based on the rationale that young people are irrational and rebellious and require fear of retribution to motivate.

Turns out, this rationale often does more harm than good. Researchers Ron Dahl and David Yeager found that underneath teenage rebellion was actually a difficult-to-admit longing for honor, respect, and prestige from their communities.33 So when they hear orders that demean their sense of competence, they’ll typically move in the opposite direction.

To show how this works, Dahl drafted an alternative to those D.A.R.E (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) and “Just Say No” (to drugs) campaigns, which historically show adverse effects – in that school districts that host them almost always see an increase in drug abuse.34

So Dahl started the “Truth” campaign which geared toward reducing tobacco usage. Rather than using the authoritarian language (“Do this, don’t do that”), Dahl made ads that showed that cigarettes didn’t have any prestige signals and were often a tool of coercion from marketers attempting to manipulate the young. Within a year of the ad’s debut, the Floridan teen smoking rates dropped from 18% to 9%.

When you tell someone, “You’re not smart enough to make good decisions, just do what I say,” it threatens their sense of competence, and temptation to rebel sets in. But when you say, “Hey, you’re really smart and often make good choices; however, did you happen to know that these tobacco companies think you’re an idiot and want to take advantage of you?” this affirms their craving for recognition while supplying motivation toward making better decisions on their own accord.

Let’s take this back to Paul. He could’ve easily commanded Philemon to receive Onesimus as an equal, but he takes the less efficient route. He affirms Philemon’s character while imploring him to act in accordance with this character for the sake of a greater good. It’s like saying, “This is who you are, and we need you for the sake of our shared mission.” That’s endlessly more motivating than “Do this because I am in charge and I know best.”

Similarly, God invites us into so much more than a “Don’t sin, idiot!” kind of relationship. He calls us His “friends” (John 15:13-15) and says we’ll do even “greater works” than Him (John 14:12-14). This is the highest prestige we could fathom. He tells us we’re trustworthy emissaries for the most important assignment in human history. That’s awfully flattering.

These are the perfect ingredients for pure, intrinsic motivation.35 As His clients, our pursuit of righteousness should flow out of thankfulness rather than a paranoia about doing enough. Our motivation can bloom from being caught up in the superabundance of His goodness as opposed to an anxious concern that His judgement might turn toward us.

This isn’t, of course, just about complimenting us and then looking the other way. As friends who’ve worked in inner city ministries attest, passively handing out gifts and hoping for gratitude isn’t all that transformative. What is transformative is taking people under your care, showing them their potential in Christ, and offering them both the resources and responsibilities to help them grow into those standards.

Now, I haven’t researched this topic exhaustively. There are likely some nuances I’m missing and counterarguments I haven’t seen. But this idea genuinely makes me ecstatic.

As I’ve written elsewhere, social scientists have demonstrated that the emotion of gratitude has more in common with what we call “happiness” than any other sensation. Framed this way, giving “thanks in all circumstances” (1 Thess. 5:18) isn’t strenuous – it’s almost like an invitation into a state of being where we’ll experience the most bliss.

To end, the past few months of researching this topic brought me back over and over to a maxim from Augustine’s mentor Ambrose. I’ve always wondered why this legendary spiritual mentor thought this was so significant, but it’s making more and more sense every day:

“No duty is more urgent than that of returning thanks.”36

Maybe he’s exactly right.

This story pops up in so many books and biographies, but the source I drew this from was Philip Yancey, What’s So Amazing About Grace? (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1997), 45. See also Scott Hoezee, The Riddle of Grace (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996), 41-43. Also! I love C.S. Lewis. This isn’t meant as a dig on him. I’m just using it as an illustration.

The great Philip Cox was the first to actually point this out to me.

Grace is one of those words in which the definition is almost entirely dependent upon one’s religious tradition. It’s also a word that’s been left disproportionately unexamined by scholarship. But the definition we’re using for this essay is John Barclay’s: it “denotes the sphere of voluntary, personal relations, characterized by goodwill in the giving of benefit or favor, and eliciting some form of reciprocal return that is both voluntary and necessary for the continuation of the relationship.” John M. G. Barclay, Paul and the Gift (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2015), 422.

This is partly because the term grace has almost no universal definition in Christian culture. It is almost as if the word has no definition because it has been defined so many different ways by so many different people. Barclay, Paul and the Gift, 14.

Barclay, Paul and the Gift, 1-21.

David deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity: Unlocking New Testament Culture (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2nd edn., 2021), 112.

Barclay, Paul and the Gift, 28.

Sophocles, Ajax, 522.

Also it’s interesting that just like how the connotations of “gift” has evolved, so have the connotations of “friendship.” deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity, 100-101.

Marcel Mauss, The Gift, trans. W. D. Halls (London: Routledge, 1990), 42, 47-48.

Seneca, Ben. 1.4.2, LCL.

Seneca, Ben. 4.18.1.

deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity, 131.

Barclay, Paul and the Gift, 28.

deSilva even notes that Onesimus was probably not a runaway slave, but a slave who departed from Philemon’s care in order to find their owner’s friends and see if their friends would make an appeal for better treatment for the slave.

deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity, 142.

Barclay gives six definitions (or “perfections”) of grace. But since this isn’t an academic article, I decided to just summarize by giving the two big definitions from the condensed version of his book. See John M. G. Barclay, Paul and the Power of Grace (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. 2020).

Matthew Thiessen, A Jewish Paul: The Messiah's Herald to the Gentiles (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2023), 138.

Martin Luther, “Two Kinds of Righteousness,” in Martin Luther: Selections from His Writings, ed. John Dillenberger (New York: Anchor Books, 1961), 86-97.

This point is implied in John Milton’s Paradise Lost 3:142. See also Miroslav Volf, The Cost of Ambition: How Striving to Be Better Than Others Makes Us Worse (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2025), 83.

Dallas Willard, The Scandal of the Kingdom (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2024), 202.

Jacques Derrida, Given Time: I. Counterfeit Money, trans. Peggy Kamuf (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 7.

Disgust is a strong word, but I’m trying to give the psychologically accurate word. When people see others break social conventions (such as not giving thanks for something that should be given thanks for), our brains usually register a sense of moral and interpersonal disgust. See Paul Rozin, Jonathan Haidt, & C. R. McCauley, “Disgust,” in Handbook of Emotions (New York: The Guilford Press, 2008), 757-776.

Seneca, On Benefits, 1.10.4.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1947), II-II, Q.107, A.1–A.2.

Jonathan Edwards, The Nature of True Virtue (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1960), 74.

Martin Luther, The Large Catechism, trans. F. Bente and W. H. T. Dau (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1959).

Miroslav Volf, The Cost of Ambition: How Striving to Be Better Than Others Makes Us Worse (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2025), 63.

I do not think Karl Barth was a good man, but this point is exceptional. Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Vol. 4 (London: T&T Clark, 2004) 41-42.

After reading Barclay’s work, I do still consider our salvation to be entirely in God’s hands and not something won through human effort.

deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity, 148.

David Yeager, 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People (New York: Little, Brown, and Spark, 2024), 31-34.

Victor C. Strasburger, “Prevention of Adolescent Drug Abuse: Why 'Just Say No’ Just Won't Work,” Journal of Pediatrics 114 no. 4 (1989): 676-681; S. T. Ennett et al., “How Effective Is Drug Abuse Resistance Education? A Meta-Analysis of Project DARE Outcome Evaluations,” American Journal of Public Health 84 no. 9 (1994): 1394-1401; Donald R. Lynam et al., “Project DARE: No Effects at 10-Year Follow-Up,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67 no. 4(1999): 590-593.

‘Intrinsic motivation’ is a psychological concept that denotes a variety of motivation that is self-propelling and ambitious in and of itself. Paul Baard et al., ‘Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of Performance and Well-Being in Two Work Settings’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34 no. 10 (2004): 2045-2068.

Ambrose, De Officiis, trans. Ivor Davidson (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001), Book 1, Chapter 26, p. 95

First off, can I just say that the caliber of writing here on Substack is so much better than I expected? I'm a newbie here, so forgive my delighted surprise. Footnoted, peer-reviewed, thoughtful analysis that satisfies my desire for academic writing as well as, dare I say, inspirational and faith-filled? I couldn't be happier to be here.

Second, I agree that a genuine experience of grace generates a response, but I'm not sure that the connotations of "strings attached" captures that dynamic. For example, the ten lepers all experienced the same degree of grace. It poured unstintingly over their desire for wholeness, but only one returned with gratitude and availed himself of a much fuller degree of grace. The grace was available to all, and only one grabbed hold of it. This doesn't feel like strings attached so much as going further up and further in. I need to read this article again because I am working on a poem about why the kingdom was ripped from Saul and given to David (who appears to have an equal degree of faithlessness from our human perspective). It's always the heart God is after, which is why it's hard to quantify grace by a human metric.

Third, the emphasis of gratitude as a pathway to joy is articulated beautifully. This is life changing. I write about this a lot in my poetry because people are so desperate for happiness, but it eludes them until they fix their gaze on gratitude, "like stars that can only be seen in the periphery." Thank you for this thought-provoking piece! And for writing it so winsomely.

Wow - what an incisvie deep-dive Griffin! "Grace that’s free from expectations didn’t enter the Western imagination until after the Reformation." - this is most certainly a hot-button topic for most evangelicas, and you lay out perfectly how grace is indeed a two-way relationship (not of expectation but invitation). I remember when I frist became a Christian twenty years ago, I was so profoundly grateful for God's forgiveness I just wanted to pour it forth. His grace had cracked my heart open, and I wanted to show it turn to everyone around me. Given today's piece, I suspect you might find resonance in the Orthodox perspective as well.

Also, love the humour you insert! I would love to see an article like this published by a Christian journal, pictures and all :)