Money Can't Control Everything. And That's Very Okay

don't forget to consider the lilies of the field and the birds of the air

Voiceover and printable pdf of this article available here!

Sigmund Freud once went on a hike through the Austrian mountainsides with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. To Freud, the summery landscape was doing everything it could to maximize its own beauty—almost like it was showing off. Vibrant greens and blues and earthy browns, the birds’ songs sounded like a sonata, bottomless fresh air for their lungs. And yet, Freud noticed that Rilke was staring at his feet the whole time.

Apparently, Rilke saw it all as a reminder that the universe was outside of his control. The flowers were all ruins in progress, every tree’s leaves a reminder of their inevitable absence come winter, every bird’s song a dirge. And so Rilke’s anxiety blocked the joy of self-forgetfulness that gorgeous landscapes famously provide.

In Freud’s opinion, our awareness of the world’s uncontrollability—that plants die, flowers fade, birds grow old—should give us more reason to enjoy it. But Rilke only saw it as a reflection of his inner concerns, turmoil, and worry.

Later, Freud used this as a case study to describe a crucial feature of a psychologically healthy person: the ability to see past the potential pain of losing something long enough to allow ourselves to unreservedly love it.1 It’s a solid litmus test—are we so fixated on control or self-preservation that we can’t get outside our own heads long enough to enjoy innocent pleasures?

Put another way, if we can’t lose ourselves in the flowers of the field or the birds of the air, there’s a good chance we’re allowing worry to run our lives.

We Can’t Control Much

There are plenty ways to gauge where we’re at in terms of worry; but one of the clearest is just considering our relationship with money. Money wins the hypothetical popularity contest of tools we use for creating an illusion of control over an uncontrollable world. It’s our go-to bandaid for anxiety.

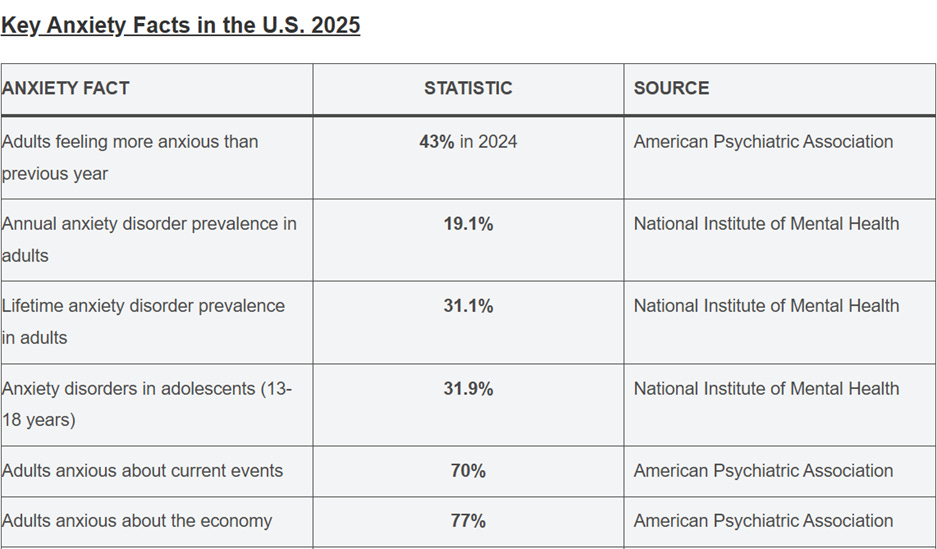

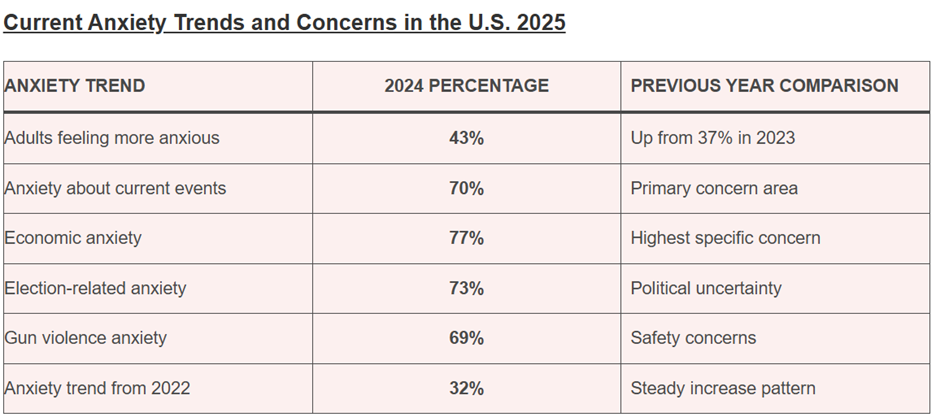

Every year, The Global Statistics throws together a meta-analysis of studies, surveys, and research on anxiety. Unsurprisingly, everyone’s pretty anxious:

And the worry that tops most lists of worries is economic concern.

It makes sense; in recent years, many have noticed that even though they’re not making less money, their paychecks aren’t going as far as they used to. That’s a real cause for concern. We prefer our status quo; if something happens that forces us to cut back on the spending that allows our status to stay quo, it can feel legitimately nerve-wracking.

In fact, economic decline reveals one of the most natural things about modern people: the idea that if we aren’t gaining, we’re losing. As the sociologist Hartmut Rosa argues, moderns live by an unspoken rule of life: “Always act in such a way that your share of the world is increased.”2

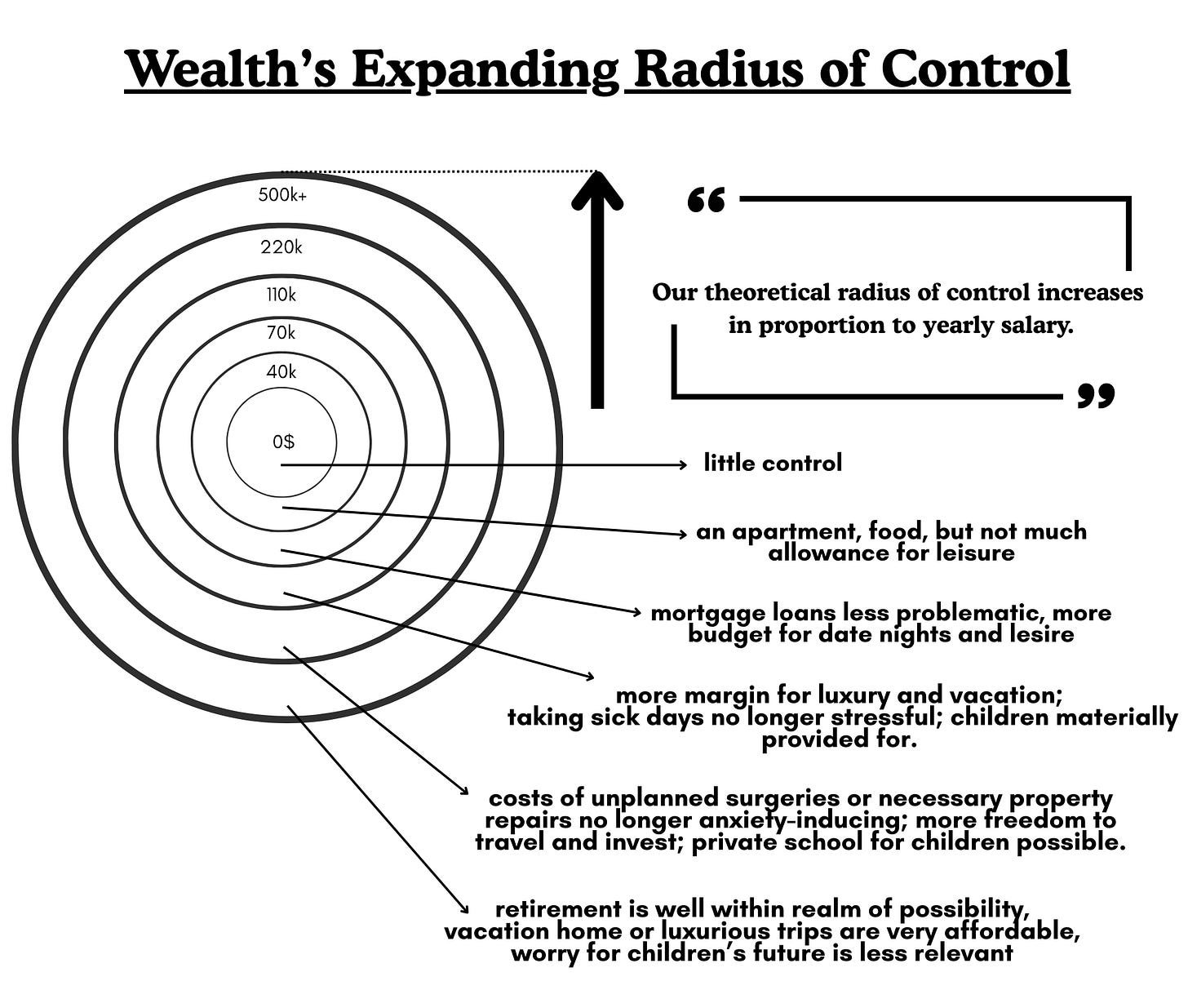

Essentially, the “promise of increasing the radius of what is visible, accessible, and attainable to us” is the script we subtly live by, informing us whether or not we’re living the good life.3 So if our radius of potential regresses—or even stays the same a little too long—it can feel like we’re failing.

As such, trading the Whole Foods grocery haul for Aldi, swapping an expensive skin-care treatment for an Amazon Basics knockoff, or downgrading the yearly Hampton stay for a campground vacation—these downgrades aren’t just experienced as minor inconveniences; they register as a slight on our humanity. Thus, money becomes the resource that shields us from the subtle humiliations of not moving up and to the right.

And it also goes to show that the root of financial anxiety—the worry under the surface worry—is the fear of losing the sense of control it provides.

Money is what Aquinas called “artificial wealth.” It isn’t the thing that our bodies actually need (i.e., the “natural wealth” of food, clothes, shelter, drinks, etcetera).4 Money is symbolic—we trade it for the literal stuff that satisfies our desires.

Think about this in terms of salary. It’s an agreed-upon standard of artificial wealth that affords us different radiuses of potential:

So when we talk about money, we’re not so much talking about the literal paper dollar bills or numbers in our bank account, but the radius of control those numbers afford.

Mammon

Interestingly, this is almost exactly how Jesus considered money.5 He wasn’t so much concerned with physical coins as the way our imaginations use those physical coins.

Which is why He talked less about money than “mammon”—possessions, property, or just the abstract idea of gaining more of whatever resources we find valuable.6 Mammon is laced with spiritual undertones, like a siren song that leads our minds inward until we can’t think about much else besides gaining more.7

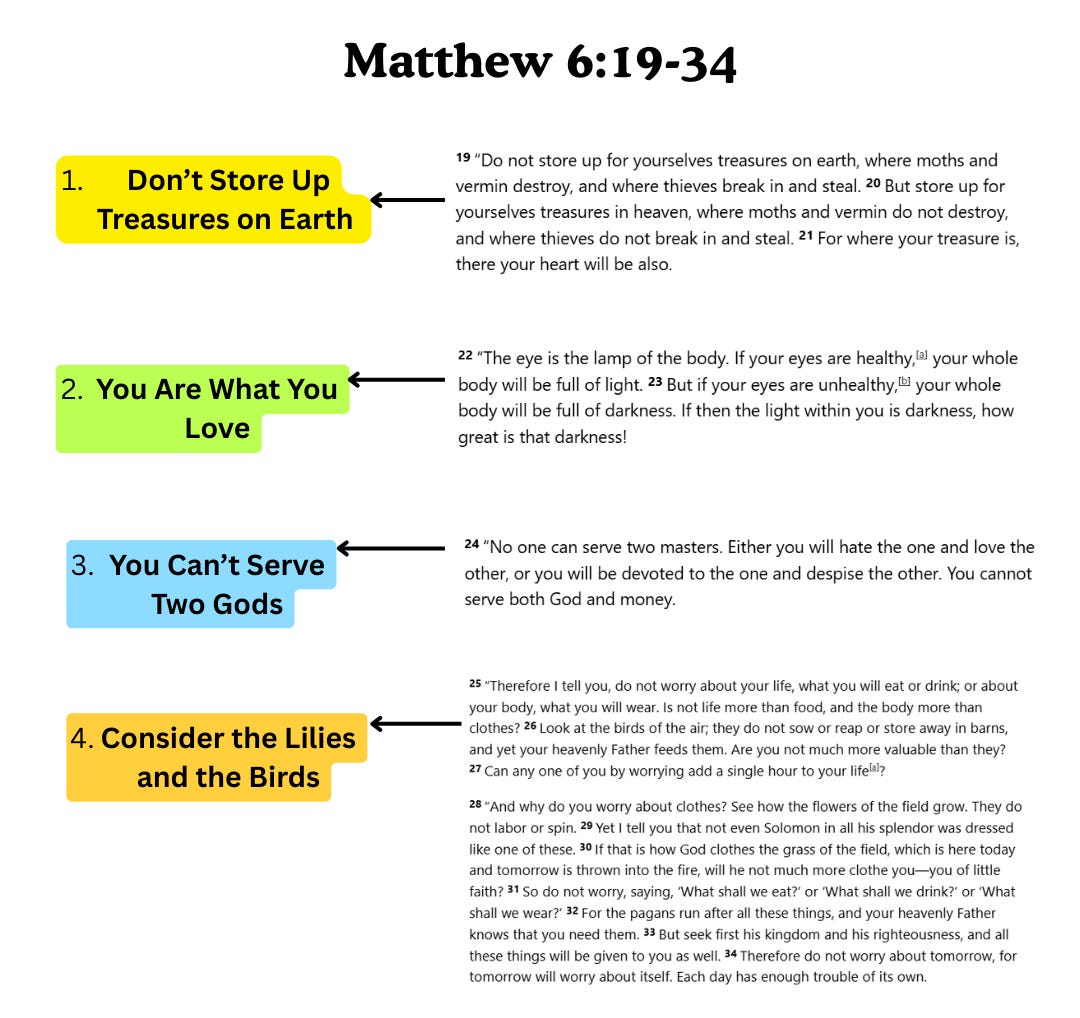

Jesus devotes four consecutive teachings in the Sermon on the Mount to mammon:

Firstly, Jesus says that we shouldn’t pile up treasures (attachments, idols, things we try to derive an ultimate sense of satisfaction from) on earth, because it will only attract trouble—along with anxiety about its eventual decay (i.e., “more money, more problems”). But if we aim toward heavenly treasures, we’ll never feel lack (i.e., “more heaven, less problems”? 10 USD to anyone who comes up with something catchier).

Secondly, Jesus tells us that our goals determine the kind of person we’ll become: “The lamp of one’s life is one’s goal; if your goal is sound, your whole life will be luminous. But if your goal is wrong, your whole life will be darkness.”8

Which makes wonderful sense considering multiple studies on money obsession. In one, researchers tracked 12,000 freshmen over the course of 19 years and found that those who listed “money-making” as their highest priority “were far less happy with their lives” than others.9 Other studies show a correlation between materialism and the likelihood of suffering from anxiety and depression.10

Thirdly, Jesus says we can’t serve two gods. If we love money more than God, we’ll end up loathing God for putting too many parameters around how we use and pursue money.

Now, we should note that Jesus doesn’t say a faithful follower can’t have money or possessions; He says we can’t serve money. And like everything Jesus said, He’s not just saying it because He doesn’t want us to sin, but because He knows what’s best for us.

As in any other addiction, the love of money can easily hijack the command center of our lives. Those who love it never get enough of it. As the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer once said, “Wealth is like sea water; the more we drink, the thirstier we become.”11

If we treat money like it’s a tool that can solve all our problems, it eventually starts using us as a tool.

So to boil down these three teachings, it’d look something like, “If we put our trust in money—if that’s what we cling to for a sense of control—we’re at risk of allowing money to rule our lives.”

Consider the Lilies, the Birds

Fourthly, in the breath after, “You cannot serve God and money,” Jesus says, “Therefore, do not be anxious.”

Which is the last thing moderns like being told. “Don’t be anxious” doesn’t earn a therapist many points with their patients.

He continues: “For life is more than food and the body more than clothing.” Which is a bit more practical. But then He gets to the crux:

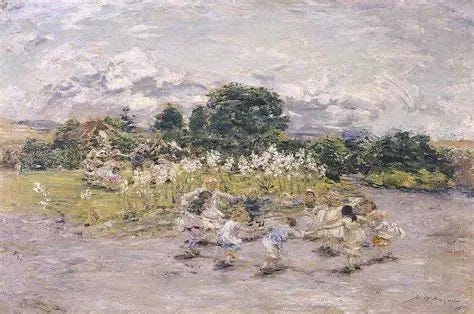

Consider the birds of the air. They don’t do much and yet your Father feeds them all. Aren’t you more valuable than a bird? And why worry about clothes? Just look at the lilies of the field. Even rich King Solomon in all his glory wasn’t better dressed than them. If God so clothes the lilies of the field, which are only alive until the seasons change, won’t He want to clothe you even more? (Matt. 6-26-30, PAR).

Admittedly, this sounds underwhelming. Birds and flowers don’t really scream “I’m free from financial anxiety.”

But in reality, if we take a pause from fretting on finances to sit and birdwatch, or walk through a beautiful array of flowers, our anxiety literally decreases. Science shows that simply looking at nature reduces anxiety.12 But the theological reasons are more fascinating (and important).

Søren Kierkegaard was obsessed with this passage. He wrote three long works all in a row that dealt with the lilies and birds.13 After finishing the first one, he felt like he missed some crucial insights, so he wrote another, and then another.

Interestingly, if you read them in order, you witness his evolution. As he starts writing about lilies and birds, he’s a detached existential philosopher. Then he moves to thinking about them in light of God’s love. Finally, by the last one, he’s writing as a man who’s allowed God to transform his anxieties through miniature reminders of His goodness: the birds, the grass, the flowers, the rodents. All belong to God, and so do we.

The lilies of the field and the birds of the air are little teachers God places in creation to remind us that things aren’t as bad as our imaginations make them out to be. They’re like a microcosm of you and I. God created them, just like He created us. He sustains them, He sustains us.

Something about the way God designed earth literally comforts us. In a study during Covid, researchers found that people who were quarantined in homes that had a view of nature outside their windows were less anxious than those who only had urban landscapes to look at; even those in the same apartment complex reported higher levels of contentment when their apartment faced greenery than cityscapes.14

Lilies, birds, and luscious foliage teach us that many of the material things we feel like we need we could actually do very well without. Like Boethius put it, “Men who possess very many things need very many things, while men who measure their abundance by the necessities of Nature and not by the excesses of desire need very little.”15

So Jesus instructs us to turn our attention toward seeking the kingdom of God. Obviously, He wants us to act as emissaries of the kingdom; but it’s also because He knows that if we seek anything else first, it'll sooner or later push our back into a wall and eat us alive. Seeking the kingdom is essentially the diametric opposite of money addiction—the more we pursue it, the freer we become.

Giving up the felt need to control the world isn’t a harrowing sacrifice. It’s the happiest choice we could ever make. And “What blessed happiness is promised to the one who rightly chooses.”16

Resonance the Good Life

Part of why nature calms us is because it helps us experience what Hartmut Rosa calls “resonance.” It’s when our mind and body and soul connect with our experience and stitches us into a transformative harmony. It’s a sort of in-tunedness with the world.

And we only really experience resonance when we’re relating to something beyond our control—trekking an Austrian mountainside, navigating a romance that seems to be going well but isn’t a sure thing, a song that unexpectedly amazes us.17 But when we try to control too much, or dim down the parts of us that appreciate the complex strangeness of the world, resonance is ruined:

If we no longer find ourselves able to effectively respond to the multitude of voices all around us, then we feel dead inside, petrified: incapable of resonance. It is symptomatic of depression, a state in which all our axes of resonance have fallen mute and grown numb, that nothing touches or moves us anymore.18

That last bit is eerily accurate. When The Corrections author Jonathan Franzen and his best friend David Foster Wallace took a road trip, Franzen drove them down a detour to stop at a bird sanctuary. Standing over a clearing gazing through a pair of binoculars, Franzen, a notorious bird watcher, lost himself in a frenzy of excitement mentally cataloguing the birds. But when he passed off the binoculars to Wallace, he merely took a two-second glance and said “Cool.”

It was this moment that Franzen realized David was truly in a horrible place—that even though he could forget his problems through a self-forgetful hobby, his friend couldn’t.19 Horrendously, Wallace succumbed to his depression within the year and ended his own life.

Don’t forget to consider the lilies of the field and the birds of the air.

I recently got an article accepted at The Journal of Psychology and Christianity about how feeling awe at God’s creation can do wonders for our overall well-being. One peer-reviewer suggested an addition: why not recommend therapists encourage depressed patients to spend time in nature?

If you know someone who’s struggling, you probably know their tendencies: they’re more likely to stay inside, see less of their friends, and wrap themselves in a cocoon of endless rumination. It’s a horrible cycle: we become depressed, and then the depression tells us to keep doing the activities that make us more depressed.

So maybe the best thing to tell a depressed person—though they’ll probably resist at first—is to go outside, breathe, become human. The randomness of seeing a deer, a passing couple acting goofy, a fork in a river that looks like a miniature waterfall—all of it remind us of the splendid uncontrollability of the external world, which, oddly enough, allows us more control over our inner world.20 Nothing gets us outside our own heads quite like outside.

Thankfully, for Rilke, his story didn’t end after his walk with Freud. One day, he’d even go on to write a poem about how hurry-addicted moderns wasted their opportunity to absorb nature’s beauty:

For them, no mountain is wondrous to see;

their properties border on God’s own domain.

Pay heed to my warning: now make your retreat.

The singing of things, not words, is what’s sweet.21

“The singing of things”—the idea that creation communicates sweetness—started long before Rilke. For the Psalmists, creation was the way the visible universe proclaims God’s handiwork (Ps. 19; Ps. 8:3–4), reveals His nature (Rom. 1:20) and showcases God’s creativity in such a way that it almost demands a response. “The whole earth is filled with awe at your wonders…Where morning dawns, where evening fades, you call forth songs of joy” (65:8).

Many early reformers saw creation was a runway for revelation. Calvin even believed we should read creation theologically.22 Some went so far as to say that God gave us two books: (1) the “divine, special” revelation of the Bible, and (2) the “general” revelation that reveals God through His creation.23

Like art aficionados studying a painting to learn more about an artist, so Christians can study nature and learn more about God.24 As one Reformation theologian put it, “All creation is the most beautiful book of the Bible; in it God has described and portrayed Himself.”25

We can’t control as much as we’d like to, and maybe God’s creation is an invitation to let us know that that’s okay.

The flowers and birds and stars don’t have 401ks or Ring doorbell security cameras, and they’re getting along just fine. So rather than encouraging more self-preservation—shoring up wealth, securing social status, grinding constantly to feel on top of our careers—creation instructs us to stop worrying so much about tomorrow and enjoy today while it’s still today.

Like Freud noted, knowing that moments, people, and things are impermanent, beyond control, and fleeting should accelerate our desire to love. Sure, we’ll feel morose when those things fade or change or move in undesirable directions; but experiencing the whole spectrum of emotions that God’s granted us makes for a much richer life than stoically muting every unpleasant one. Feeling it all, seeing it all as a gorgeous extension—an uncontrollable tapestry—of God’s goodness, is one of the best ways to be human.

Don’t forget to consider the lilies of the field and the birds of the air.

Many assume this hike was a fictitious imagining to illustrate Freud and Rilke’s differing opinions. See Sigmund Freud, “On Transience,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 14, translated by James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1957), 305–310. I first heard this story in Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006).

Hartmut Rosa, The Uncontrollability of the World, trans. James C. Wagner (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020), 11. Technically, he calls this our “categorical imperative.”

Rosa, The Uncontrollability of the World, 11.

Thomas Aquinas, ST, q. 2, a. 1.

Philip Goodchild, Theology of Money (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 1-8, 12-13.

Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary, Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 479.

W. D. Davies and D. C. Allison Jr., Matthew, Vol. 1 (Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1988), 643. It should also be noted that the progression in terms of how God’s people should relate to money is distinct between the Old Testament and the New. As Craig Blomberg notes, the OT notion that money is a sign of God’s blessing and a sign of one’s hard labor is not an idea that carries into the NT. Instead, money is seen more critically, with its potential for corruption receiving much more ostensible and blatant treatment. In fact, nowhere in the NT is money depicted as God’s direct reward for His imagers. See Craig L. Blomberg, Neither Poverty nor Riches: A Biblical Theology of Possessions (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 1999), 83, 145.

This is Frederick Dale Bruner’s translation of the phrase.

C. Nickerson et al., “Zeroing in on the Dark Side of the American Dream: A Closer Look at the Negative Consequences of the Goal for Financial Success,” Psychological Science 14(6) (2003): 531-36.

Raj Raghunathan, If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Happy? (New York: Portfolio, 2016), 54.

Arthur Schopenhauer, “Parerga and Paralipomena,” in Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays, trans. E. F. J. Payne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974).

S. Grassini, “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nature Walk as an Intervention for Anxiety and Depression,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 11 no. 6 (2022): 1731.

See his Upbuilding Discourses, Christian Discourses, and Three Discourses (the modern title of the last one is now The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air).

M. Soga, M. J. Evans, K. Tsuchiya, and Y. Fukano, (2021). “A Room with a Green View: The Importance of Nearby Nature for Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Ecological Applications 31 no. 2 (2021): e2248.

Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, 48.

Søren Kierkegaard, Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, ed. and trans. Howard and Edna Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 205-206

It should be noted that Rosa doesn’t think that just seeing something appealing can create resonance; it has to challenge us or confront us with its uncontrollability in some way or another. See Hartmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of our Relationship to the World, trans James Wagner (London: Polity, 2019).

Rosa, The Uncontrollability of the World, 34-35.

Jonathan Franzen, “Farther Away,” in Farther Away: Essays (New York: Picador, 2013), 38.

J. M. Burger, “Desire for Control, Locus of Control, and Proneness to Depression,” Journal of personality, 52 no. 1 (1984): 71–89; Liam Alexander Myles, MacKenzie, Emanuele Maria Merlo, and Antonia Obele, “Desire for Control Moderates the Relationship Between Perceived Control and Depressive Symptomology,” Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 8, no. 2 (2021): 299–305.

From Rilke’s “Ich fürchte mich so vor der Menschen Wort.” Oh you don’t know German? Not my problem, bub.

John Calvin, Institutes, 1.5.4 (55-56).

Philip Graham Ryken, “Past, Present, and Future,” in Habits of Hope (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2024), 34.

Obviously, there’s a line. Some medieval kooks argued that we could worship foliage and architecture as if those things were God Himself. We don’t worship creation; the awe we feel toward creation leads us to an awe of God.

Lots of people think that Martin Luther said this, but there’s unfortunately not much evidence that he did.

Brilliant Griffin! Your emphasis on going out to enjoy creation is music to my ears as someone who writes much (and waxes lyrical) about creation, nature and creation stewardship. One of my best reads of 2025 was 'The Language of Rivers and Stars' by Seth Lewis, which I reviewed for the Gospel Coalition. It is a book in which argues creation is speaking to us about God, and its main message goes well with your piece: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/reviews/language-rivers-stars/

On your “more heaven, less problems”, is this necessarily true? Jesus says, followers of Him will have tribulation and suffering, more problems(!) perhaps for following Him. But then, in the next breath He says "take heart for I have overcome the world". So, maybe it's more accurate to say, "more heaven, more peace", which is what Psalm 23 is saying: even in the midst of the valley of the shadow of death (big, huge problem!), I will not fear, for you are with me - and, to bring in another few paraphrased Psalms: in the midst of all my problems I can lie down and sleep, for you are with me and will keep me in perfect peace. The more I focus (meditate) on You, the more peace I have.

This is a peace that in Heaven will be complete, eternal, and unshakable -- and completely problem free.

Solid piece on reframing anxiety around control. That Freud-Rilke anecdote really captures how future-worry kills present joy, and linking it to mammon makes total sense because financial stress is basically control-seeking on steroids. I've noticed this in my own life were reducing spending on nonessentials actually made me happier, not more restricted. The resonance idea connects well too, when we're constantly trying to control outcomes, we miss those unplanned moments that actually feed the soul.