The Power of Elevation

Why Feel-Good Stories Make You Feel Good, Purity vs Pollution, and Paying Attention to the Remarkable Ordinary

Here’s a story:

Myself and 3 guys from my church were going home from volunteering our services at the salvation army that morning. It had been snowing since the night before and the snow was a thick blanket on the ground. As we were driving through a neighborhood near where I lived I saw an elderly woman with a shovel in her driveway. I did not think much of it, when one of the guys in the back asked the driver to let him off here. The driver had not been paying much attention so he ended up circling back around towards the lady's home. I had assumed that this guy just wanted to save the driver some effort and walk the short distance to his home (although I was clueless as to where he lived). But when I saw him jump out of the back seat and approach the lady, my mouth dropped in shock as I realized that he was offering to shovel her walk for her.1

Afterwards, the woman narrating this experience recalled feeling physically and emotionally changed. She reported an expansion in the chest along with a sense of levity, hope, warmth, joy, and a desire to recreate the act of kindness she just witnessed.

Importantly, this anecdote also inspired psychologists to dig deeper into the emotion of elevation.

1. Religious Emotions

Along with gratitude and awe, elevation belongs to a unique trio of emotions called the “religious,” “moral,” or “others-praising” emotions.

A growing body of empirical studies are finding that this trio might have more influence on our subjective wellbeing than the typical feelings we might associate with happiness, such as pleasure or success.2

They’re unique in that they give us both a social focus (“a desire to be with, love, and help other people”) and a religious focus (a transcendent sense of wonder about the universe).3

As such, they’re all incredibly important for spiritual formation. But, of the three, elevation might be the most directly related with spirituality.

2. What is Elevation?

Elevation is what we feel when we witness moral beauty. It’s characterized by “sensations of warmth and expansions in the chest”4 and a desire to mimic the behavior witnessed.

Elevation provides a sense of weightlessness that can mute anxiety over finances, popularity, or self-preservation. This is because it silences the “default self” – what Aldous Huxley described this as “the interfering neurotic who, in waking hours, tries to run the show.”5

One study split 129 college students into two groups and showed each a different Sarah McLachlan music video. The control group watched McLachlan’s “Adia” video, which displays McLachlan singing in various urban backgrounds. The test group watched McLachlan’s “World on Fire” video, which explains how McLachlan decided to spend all but $15 dollars of her $150,000 dollar music video budget on global charities. After paying them for participating in the study, the researchers gave the students the option to give some of the money to charity. As expected, the “World on Fire” group gave significantly more than the control group.6

The most profound elevation experience in my own social circle came after my friend dropped out of med school. After beginning his residency, he started having panic attacks every day. Then came sleepless nights, rapid weight loss, and cold sweats. He felt like his only choice was giving up. And so he did – after racking up almost a decade of loans.

Then an anonymous stranger from church paid off his 200,000 dollars of student debt. After they saw the check, everything felt weightless. The look on his pregnant wife’s face was indescribable. It’s like every concern of every person in the room vanished for a few hours. The memory alone gives me chills.

On an unrelated though no less crucial note, many studies found that when subjects witnessed others performing acts of elevation, many developed crushes on them.7

In other words, kindness is hot.

(Just some advice for my single friends)

3. Elevation/Disgust, Purity/Pollution, Shalom/Rah, Heaven/Hell

Elevation is the opposite of “disgust,”8 which is the universal reaction to bacterial or moral grossness.

Disgust, like elevation, is unique in that it’s not just about seeing something physically dirty, it also comes through seeing something spiritually or morally dirty. It’s sparked by cockroaches and dirty bathrooms as much as people cutting in line or vandalizing religious sites.9

This spectrum is similar to that of “purity” and “pollution” that was common in the ancient world.10 If that sounds unfamiliar, just think of all the Levitical guidelines about what makes someone unclean or how to regain cleanness.

The largely pagan Greco-Roman society shared similar beliefs. When the mythical Oedipus attempted to rest at a sacred grove, a stranger approaches and says, “First move from where you sit; the place is holy…Most dreadful are its divinities, most feared (Col. 36-40). Oedipus then has to cleanse himself through ritual libations and prayers to regain purity (Col. 466-490).

Every human culture has some kind of radar that detects pollution and purity, commonness and uncommonness, elevation and degradation. And this radar operates on two levels: the aesthetic and the moral.11

This is because, on a subliminal level, humans interpret pollution as a fundamental disordering of the world, while cleanliness and symmetry signal a right ordering – or “things as they should be.”

As the scholar Richard Nelson wrote, “That which is clean may be thought of as that which is in its proper place within the boundaries established by God in creation.”12

This is why we feel degradation or disgust when the greedy take advantage of the innocent and feel elevated when there’s a comeuppance for the injustice.

In fact, scientists who’ve analyzed thousands of narrative arcs boil down their pattern to that single word: comeuppance (i.e., when justice is served).13 Basically, this moral radar is so hardwired into us that we feel gipped if our plots don’t set wrong things right.

Elevation is our brain’s reaction to moral beauty – or, in my worldview, our brain’s reaction to witnessing the Kingdom of Heaven breaking into the present reality.

What I mean by that is that whenever someone is healed, rescued from injustice, or provided for in their lack, that action’s physical/social/monetary restoration isn’t the only angle effected – there’s also a metaphysical effect.

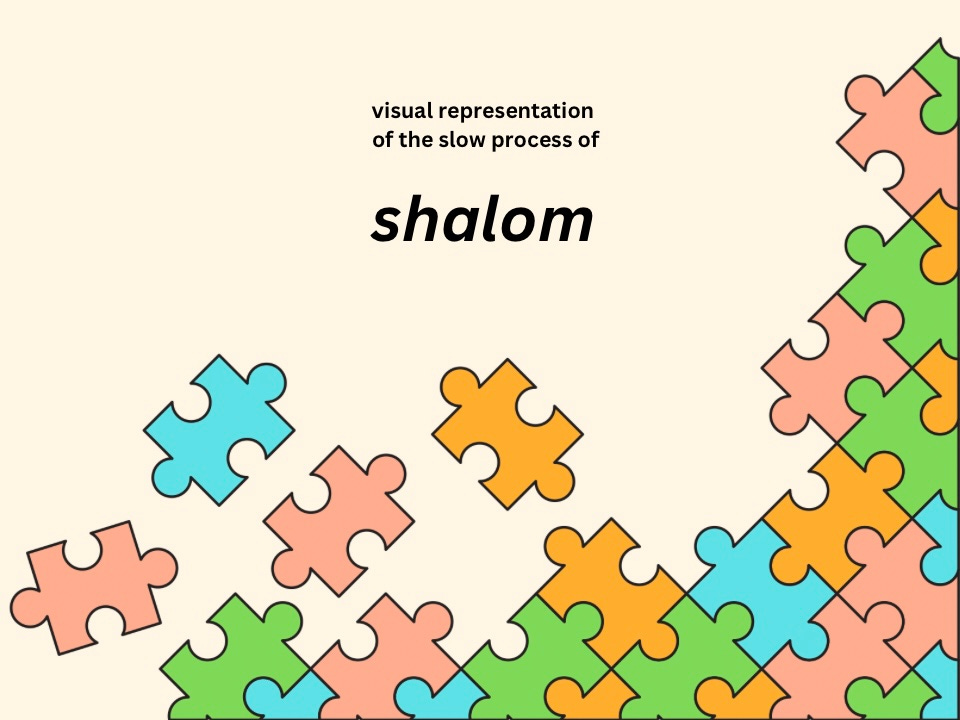

It’s a lot like the Hebrew idea of shalom, which is about way more than mere peace or ceasefire. As philosopher Cornelius Plantinga notes, in Biblical theology, shalom is meant to convey an eschatological state of “universal flourishing, wholeness, and delight.”

It’s the opposite of rah, which describes badness, disorder, or things falling apart. Shalom “is the way things ought to be.”14 It’s the process in which the disordered puzzle pieces of our world are, at least momentarily, brought back together.

Every act of elevation is like adding another patch to the tattered tapestry of our reality. Elevation makes earth more like heaven, degradation makes it more like hell.

Acts of elevation offer a foretaste of a time when there won’t be a need for medicine or racial reconciliation or poverty relief. And our brains and bodies cannot help but rejoice when we see it.

4. Why We Ignore Elevation

During this research, I continually read about the power of uplifting, inspirational stories.

But then I noticed something in myself: why didn’t I like hearing these stories more?

On one hand, elevation explains why we’re drawn to stories of firefighters risking their lives or when a Make-a-Wish child sees their dream come true.

But conversely, it also explains why we don’t like these stories. It’s hard to carry about selfish interests after witnessing sacrificial kindness. Part of you has to deliberately suppress the reciprocity impulse. But that suppression guarantees a nagging tinge of guilt for not doing what you know, at some level, you should’ve done.

Which is just about right where I was at. These stories literally compelled me to put down my self-serving tasks and be a loving presence in the world. And embarrassingly, sometimes I preferred the comforts of my daily routine.

I can’t help but wonder if this explains why anti-hero narratives have become more popular than conventional, self-sacrificial hero stories. Anti-hero stories can leave you feeling okay about yourself (i.e., at least I’m not as bad as Tony Soprano, Walter White, or Don Draper), while self-sacrificial narratives can leave a guilty conscience (i.e., because it’s hard to pretend you’re as sacrificial as Harry Potter, Frodo, or Luke Skywalker).

Elevation stories, for better or worse, reveal the state of our hearts.

But this litmus test is for the best: what about these stories rubs us the wrong way? Once we find that out, we can work backwards to the roots of our cynicism and orient ourselves to contribute to the shalom of our social contexts.15

5. Habits of Elevation

The more we experience elevation, the closer we’ll feel to God and others – and the more content we’ll feel in general.

But living more in line with this reality requires some behavior modification (or heart sanctification). Especially if you, like me, sometimes find elevation reports less than thrilling.

In other words, to become the kind of person who’s naturally altruistic, we should build regular habits of witnessing and contributing to elevation. Elevation is self-reproducing — the more we’re prone to look for it, the more we’ll find it.16

And if this sounds a bit self-help-ish, that’s because it kind of is.

I loathe self-help as much as the next person, but I unfortunately can’t shake the fact that some of it’s accurate.

If you read Spirit of the Disciplines by Dallas Willard side-by-side with The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg, you’re going to notice similarities.

Spiritual formation and expertise scientists overlap in that they both realize that growth happens through modifying our behaviors, and behaviors are usually modified through habits.

The difference is that self-help is for self help; spiritual formation is for God and others.

So, even though the three religious emotions will get you as close to a lasting feeling of “happiness” as you’ll get on this side of the New Creation, that’s not the point.

Their purpose is to color in better mental representations of who God is so that we can better exemplify who God is. Anxiety alleviation isn’t the main goal.

So, what kind of habits produce elevation?

Volunteering for a homeless shelter – or really, any philanthropic organization – is a surefire strategy.

But sadly, the number of people who volunteer or say they’re willing to is on the decline. It’s unfortunate, but it might simply reflect the state of the world.

The average person is worried about how things are progressing economically, socially, and politically. This puts us in survival mode, which makes for scarcity mindsets concerning our money and time. And few things seem more redundant to someone in a scarcity mindset than volunteering.

But it’s precisely our willingness to continue serving even when we feel like we’re the ones who need serving that dismantles scarcity mindsets.

This is why people tend to experience anxiety relief after donating. Similarly, studies find that spending time compassionately helping others leaves us feeling far more rejuvenated than spending time on self-care.

But even if you can’t squeeze more into a busy schedule, you can still fill your mind with stories of elevation from a distance.

Simply reading Biblical passages like Jesus’ feeding of the five thousand or the Good Samaritan story is enough to incentivize moral behavior (which just adds to the laundry list of reasons we should mediate on the life of Jesus daily).17

There are hundreds of Youtube videos that show generosity, books about Corrie Ten Boom or Harriet Beecher Stowe or Dorothy Day or MLK Jr., and so very many simple things you can surround yourself with daily to see the Kingdom of Heaven break in.

And yes, much of this is overwhelming; personally, I get overwhelmed. There’s a remarkable amount of evil, decay, and corruption in our world. But I’m trying to keep in mind that pursuing good isn’t about reaching a plateau in which everything is forever good – that won’t happen until Jesus returns.

Rather, I simply want to believe that there is a cumulative effect to choosing more good than bad, to doing “the next right thing”18 more than the next wrong thing.

So to remind myself of that, I’ve been trying to habituate this line from a Puritan prayer for whenever I start feeling dragged down by the weight of moral pollution:

I appeal to you,

In greatest freedom,

To set up thy kingdom

In every place where Satan reigns.

It’s a small invocation, but it helps. It makes me visualize the process of a polluted world becoming purer, good extinguishing evil, and God taking reign over territory outside His effective control.

6. The Remarkable Ordinary

We need more elevation stories. This is why I’m starting a new side project called The Remarkable Ordinary.

This idea grew out of my frustration with news platforms going out of their way to highlight the bad, the doom, and the moral degradation. They use (typically) real life events to paint an abrasively inaccurate portrait of real life.

This structure essentially guarantees that on the rare occasion a church does get brought up, it’s almost always in reference to some scandal, moral failure, or hypocrisy.

I’m tired of hearing those. And so are my friends and family. Their prioritization leads many to genuinely believe that scandals are the norm rather than the exception.

This is not the case at all. We just don’t hear about the good because social media algorithms and “if it bleeds, it leads” journalism ensures that only the bad floats to the surface.

The Remarkable Ordinary is hoping to do the exact opposite. It’s anti-moral failure, anti-hypocrisy, anti-scandal journalism. It’ll almost be like a Christian-focused version of John Krasinski’s “Some Good News” or David Byrne’s “Reasons to Be Cheerful.”

I’m deliberately zoning in on “ordinary” stories because I believe it’s important to emphasize that acts of altruism are a normal outflow of Christian faith. Ideally, these elevation reports will spread hope in our brothers and sisters along with the inspiration to mimic their goodness.

In a few weeks, I’ll start sending out a 200–500-word elevation report from either myself or a guest on Fridays. Each story will highlight some elevation-inducing act of quotidian Christian kindness, altruism, or integrity.

It’s a small, simple idea. But I really believe that the more we notice the remarkable in the ordinary, the more we’ll believe that goodness is happening, and the more inclined we’ll feel to contribute ourselves.

Thanks for reading. This is technically part five of a longer series. In case you missed it, here’s one, two, three, and four. Part six, the official finale, to come soon.

Jonathan Haidt, “The Positive Emotion of Elevation,” Prevention & Treatment 3 (2000): 2.

Patty Van Cappellen, “Rethinking Self-Transcendent Positive Emotions and Religion: Insights from Psychological and Biblical Research,” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9, no. 3 (2017): 254-263; David DeSteno, How God Works: The Science Behind the Benefits of Religion (New York: Viking, 2022), 59-64; José J. Pizarro, et al, “Self-Transcendent Emotions and Their Social Effects: Awe, Elevation and Kama Muta Promote a Human Identification and Motivations to Help Others,” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 709859; Sara B. Algoe & Jonathan Haidt, “Witnessing Excellence in Action: The “Other-Praising” Emotions of Elevation, Gratitude, and Admiration,” Journal of Positive Psychology 4 no. 2 (2009): 105-127.

Haidt, “The Positive Emotion of Elevation,” 3; Sara B. Algoe & Jonathan Haidt, “Witnessing Excellence in Action: The “Other-Praising” Emotions of Elevation, Gratitude, and Admiration,” 105-127; DeSteno, How God Works, 58-61.

DeSteno, How God Works, 60.

Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception: And Heaven and Hell (New York: Harper Perennial, 2009), 53.

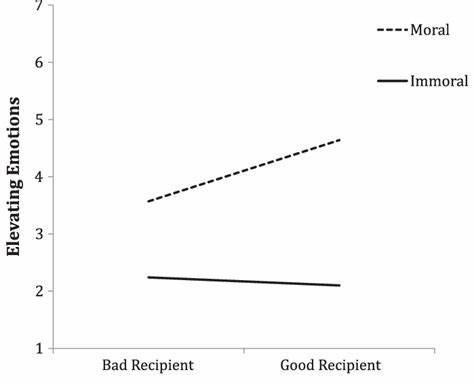

Karl Aquino, Brent McFerran, and Marjorie Laven, “Moral Identity and the Experience of Moral Elevation in Response to Acts of Uncommon Goodness,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100, no. 4 (2011): 703-718.

Haidt, “The Positive Emotion of Elevation,” 3.

Jonathan Haidt, Rozin, P., McCauley, C. R., & Imada, S., “Body, Psyche, and Culture: The Relationship Between Disgust and Morality,” Psychology and Developing Societies 9 (1997): 107-131.

Haidt, “The Positive Emotion of Elevation,” 2-3.

David A. deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity: Unlocking New Testament Culture (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2nd edn., 2022), 273-278.

Jerome Neyrey, “The Idea of Purity in Mark's Gospel,” Semeia 35 (1986): 93; deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity, 291; Haidt, “The Positive Emotion of Elevation,” 2-3.

Richard Nelson, Raising Up a Faithful Priest: Community and Priesthood in Biblical Theology (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1993), 21.

See Will Storr, The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better (New York: WillAbrams, 2020); William Flesch, Comeuppance (Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press, 2009).

Cornelius Plantinga, Jr., Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be: A Breviary of Sin (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995),10.

Yet this isn’t to say that every uplifting story is helpful. There’s a line where treating certain hero narratives as normative can’t do anything but induce shame. Dallas Willard noted this about the story of John Nelson “Praying” Hyde. It’s a great story: Hyde left a tenured academic post to go on mission in India. Once there, he scarcely stopped praying – literally. He skipped meals, rarely slept more than an hour or two a night and kept this pattern for years. Through his prayers, millions came to know Jesus. Which is an amazing, inspiring story. But this amount of intercessory prayer is not normative. And if we douse ourselves in stories like Praying Hyde or fiery revivalists as if they are the standard rather than the exception, we will not feel elevated – we will just feel ashamed at our inability to measure up.

Andrew Thomson & Jason Siegel, “A Moral Act, Elevation, and Prosocial Behavior: Moderators of Morality,” The Journal of Positive Psychology 8 (2013): 50-64.

Simone Schnall & Jean Roper, “Elevation Puts Moral Values into Action,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 3 no. 3 (2012): 373-378.

One thing I noticed is the stories that elevate us are not ones we tell about ourselves, but ones that are witnessed, mostly unexpectedly, in the acts of others who are not seeking attention through their actions. I think self-promotion of one’s charitable work and such in social media sucks the air out of the balloon. In fact, the selfless acts that are clearly not attention-seeking, in my opinion, elevate us most effectively.

Thanks for a fantastic article. As one weary of the news cycle’s fixation on the horrific, I look forward to your book!

This was wonderful! Lately I've been thinking about the staying power of stories that emphasize goodness and elevation--have been in the midst of a Tolkien deep dive and his work acts that out so thoroughly. Lots of good stuff to consider about enchantment, transcendence, elevation, and their interplay.