The Tried and True and Unsurprising Surefire Way to Find Happiness

The Beatitudes, Metaphysics of Flourishing, and the Boringly Unoriginal Way to True Joy

Audio voiceover available here for paid subscribers!

I didn’t care how it looked — I just wanted to say the words over and over and over again.

I’d just woken up in Traverse City, Michigan on a midsummer worktrip. I was 22. I left the hotel first thing for a prayer walk up and down the coast. To stifle the caffeine craving and ease my mind into an orthodox headspace, I started by reciting the Scripture I’d just memorized.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven…”

Now I, like most non-sociopaths, am frustratingly concerned with looking cool and generally not weird. But that morning I was way too excited to care. I walked up and down the beach saying the words out loud and confusing passerbys.

After I got off work, I went back to the hotel room and started from the top. I’d recite the Scripture and walk the room in a circle, stepping up and over the bed rather than going around it to maintain a more circular circle.

This wasn’t a legalistic compulsion; I was inspired by an irresistible joy that those words came from a God who took on human form and delivered them while seated on the side of a hill.

Everyone has some passage of Scripture they’ve found so mesmerizing that simply turning the words over in their minds brings a sense of wonder, peace, and wholeness.

For me, it’s the Sermon on the Mount.

I’ve never found an adequate way to articulate how or why these three chapters mean so much to me. They just do.

Some call the Sermon Jesus’ “manifesto” of the kingdom.

Augustine said it was “the charter” or “perfect measure of the Christian life.”1

John Chrysostom thought it provided the vision for the kingdom community that Jesus was establishing on earth.2

Aquinas called Matthew 5-7 the “written form of the new law of Christ.”3

A few years back, I heard that the early church committed the three chapters to memory. So I took April-May of 2020 to burn it in my own memory. And to this day, I still have “Recite SotM on the way to work on Tuesday” etched into my weekly schedule.

Anyways, I taught a couple guest lectures on the Sermon recently, and memories about my love for it flooded back.

I hope to write a whole book on it one day, maybe when I’m like 40 or 50. But for now, a couple essays on why I find the Sermon so fascinating, beautiful, and bottomless should suffice.

Let’s start with how the Sermon is Jesus’ invitation into the good life.4

Matthew 5:3-12 (“Blessed are…”)

Before we get into the actual words, we gotta talk about “kingdom.”

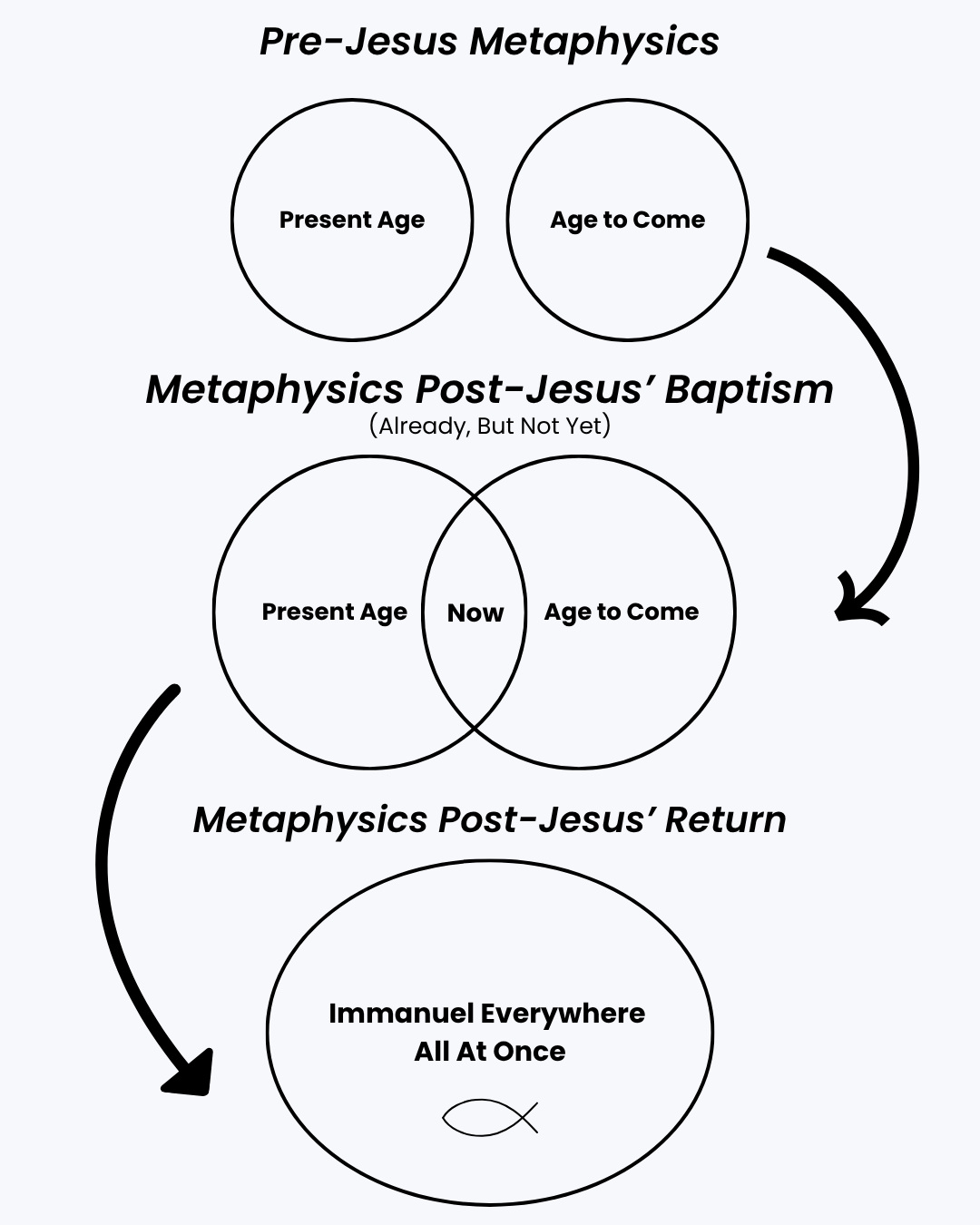

It’s way more than militaristic jurisdiction or something to crochet on wall ornaments. “Kingdom” is the “range of God’s effective will” — where “what God wants done gets done.”5 When heaven opened over Jesus at His baptism (Matt. 3), it marked the point in history where God laid the foundations for His eventual eternal home on earth via Immanuel (“God-with-us”).

Now, many of you probably know this, but the Bible didn’t have chapter divisions until Stephen Langton added them in the 1200s, and verses didn’t show up until Robert Estienne’s work in the 1550s.6

This helps us remember to read the Sermon as if it flows seamlessly from the preceding events — namely, Jesus’ baptism, squaring off with the devil in the wilderness, rounding up the disciples, healing the sick, and speaking these two phrases:

1. “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand”

2. “Follow me and I will make you fishers of men.”

The Sermon isn’t a disjointed, random speech; it’s the crescendo following Jesus’ anointing, the defeat of His primary opponent, the gathering of His cabinet, and the announcement of the new kingdom order. It’s like an inaugural address.

As such, it’s the proclamation the Jewish people have waited 42 generations for—an intro to the Messiah way of life that can finally bring rest to restless souls.

What Is Blessed?

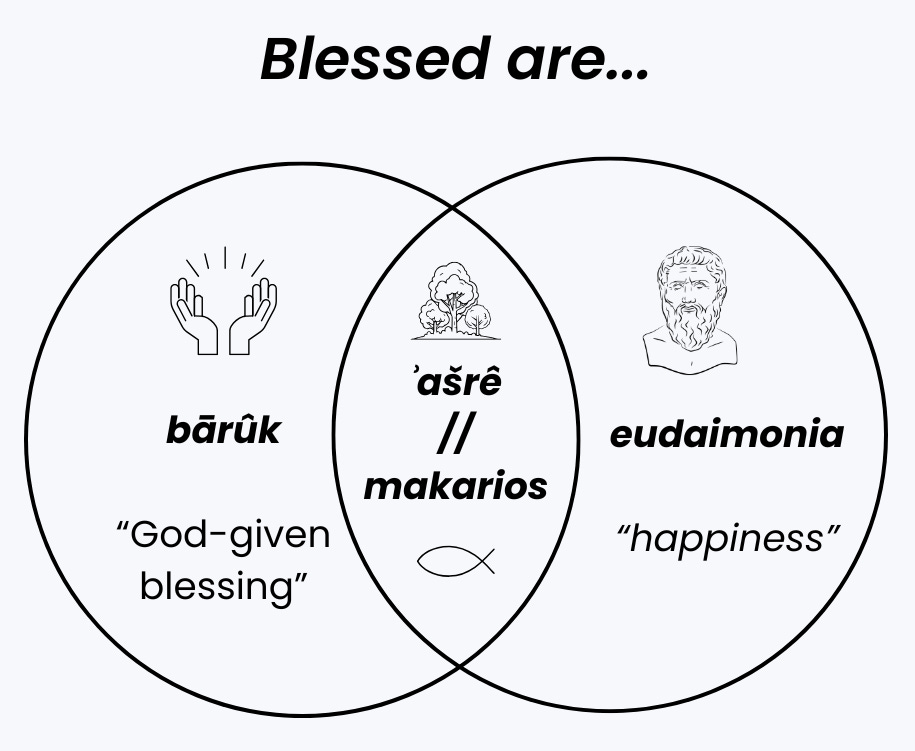

To set the stage extra, the context Jesus preached in was both heavily Jewish and heavily Greek.

Which is important because the word Jesus kicks off the Sermon with (makarios) was loaded with meaning for both Jew and Greek.

Whereas Jewish culture zeroed in on what made a person “blessed” (ʾašrê or bārûk), the Greeks were more fixated on “happiness” (eudaimonia and/or makarios).7 Jesus triggers both ideas.

ʾašrê

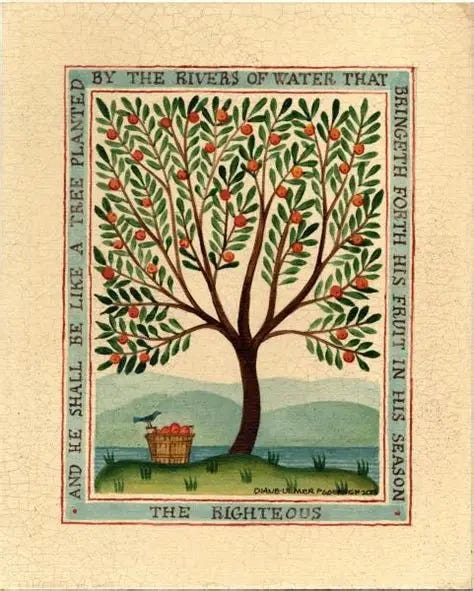

In Psalm 1, the kickoff to the most popular Jewish scripture in circulation, we find a description of what makes someone “blessed” (ʾašrê). “Blessed is the one who doesn’t accept the counsel of the wicked…he’s like a tree planted by water…in all he does, he prospers.”

Now, when we read “bless,” many often think of it in terms of, “If you do x, God will reward you with y.”8 But ʾašrê is more so declaring what makes a person flourish. It’s essentially saying that those who avoid the council of the wicked make a choice that’s naturally self-rewarding.

Take for example the very relatable scenario of a neighbor inviting you to come over and ingest cocaine before robbing a bank. If you reject the invite, God will obviously smile at your prudence; but the prudence itself is also part of the blessedness. Since cocaine and bank robberies have a 0% possibility of bringing about goodness in your life, then not robbing a bank is the choice that will obviously make you happier.

Basically, ʾašrê isn’t describing a karmic, God-rewards-us-tit-for-tat-when-we-do-good-stuff kind of idea. Instead, it’s about the way that abiding by God’s ways naturally causes us to flourish personally, relationally, and circumstantially.

makarios

This is the actual word that starts the Sermon—and it’s a mainstay term Jesus chooses for describing those who enter the kingdom of heaven.9

While scholars have fought over the best way to translate makarios, a 1st century listener would’ve heard it as a blanket word for God-given happiness or good fortune.10

All the best ideas of human flourishing, joy, and contentment are bottled up in this single term. Which is why my personal favorite way to translate makarios is simply “happy.”11

But it’s not just emotional or psychological happiness—it’s a way of being in the world that naturally results in flourishing.12 In that sense, it’s almost exactly like ʾašrê. In fact, whenever the authors of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament) translated ʾašrê, they always, without fail, used makarios.13

Makarios is like a state or activity of receiving or experiencing happiness, and it’s inextricably tied with the moral life.

Now, modern ears don’t typically hear “happiness” and think “ethics.” But the ancients (Aristotle, Cicero, the Psalmists, etc.), saw them as entirely related. You couldn’t live the good life without living an ethical life.

Several centuries before Jesus, Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle normalized the idea that the pursuit of happiness was the natural human instinct. And each essentially taught that we could fulfill this universal instinct by ordering one’s life toward virtue, justice, and truth-seeking.14

While there’s no way to know whether Jesus read Aristotle, it’s believed that Aristotle’s ideas of happiness were so popular that they became the water that the 1st century swam in.

So essentially, everyone, both Jew and Greek, was anxiously waiting to understand how to flourish — how to be happy. Jesus’ Sermon, and its accompanying way of life, is essentially one long response to this universal longing for fulfilment. It’s why NT scholar Scot McKnight wrote that the “entire history of the philosophy of the ‘good life’ and the late modern theory of ‘happiness’ is at work when one says, ‘Blessed are…”15

The Beatitudes

Many sadly tend to write off the Beatitudes as if they’re a strange detour before Jesus’ more cerebral, theological teachings. But this is so unfortunate, because the Beatitudes are “Christ’s answer to the question of happiness.”16

Jesus sits down and says, “Makarios are the poor in spirit…Makarios are those who mourn…Makarios are the meek…those who hunger and thirst for righteousness…the merciful…the pure in heart…the peacemakers…those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake” (Matt. 5:3-12).

Now, what should jump out to both ancient and modern listeners is the way these qualities have no resemblance with what we think of as a #blessed life.

But that sense of shock and confusion is both brilliant and intentional. It’s almost as if Jesus is satirizing those who try to find happiness along the #blessed routes of wealth, status, and luxury.

Rather than praising the rich and proud, He raises “the poor in spirit” (i.e., the humble, the unassuming, the powerless). Rather than lift up the ecstatic, He says happiness belongs to “those who mourn” (i.e., those experiencing the reality of suffering or loss, or those grieved by the things they’ve done that’ve hurt others).

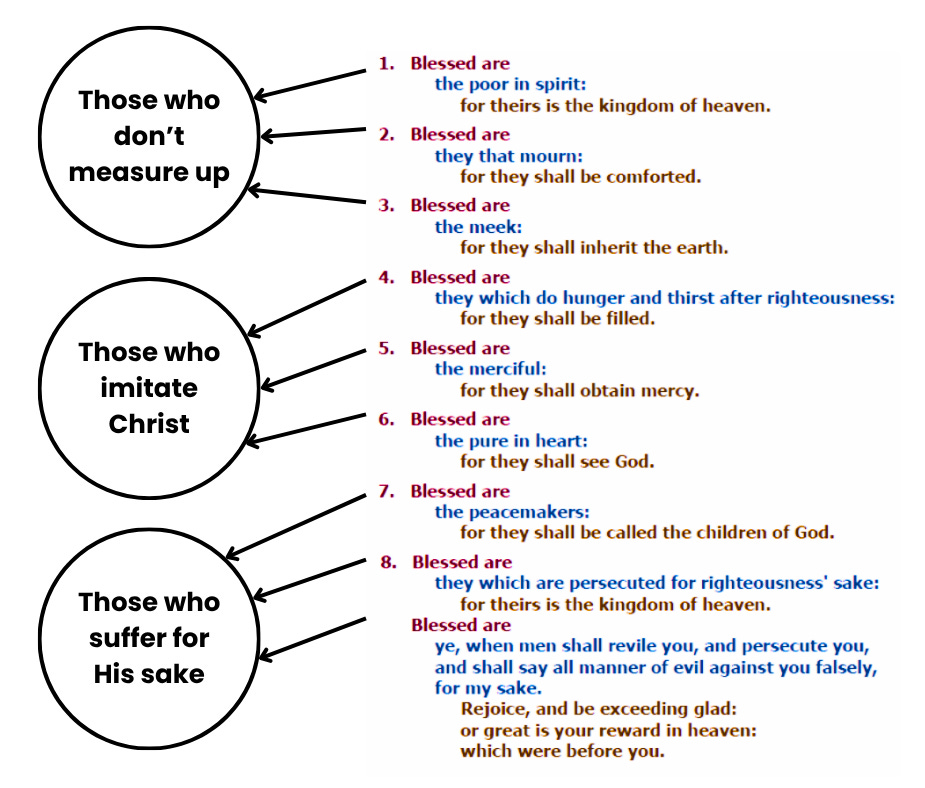

In Frederick Dale Bruner’s understanding, the Beatitudes announce makarios for

(1) people who don’t measure up in the world’s sight,

(2) those who imitate Christ’s purity, peacemaking, and longing for God, and

(3) those who suffer while trying to live up to Christ’s calling.17

The NT scholar R.T. France elaborates further: the Beatitudes “call on those who would be God’s people to stand out as different from those around them, and promise them that those who do so will not ultimately be the losers.”18 By undervaluing the things the world calls “good,” Jesus’ words makes us more available to the “highest good,” as Søren Kierkegaard put it.19

The theologian Servais Pinckaers offers my favorite take on the Beatitudes:

We can compare the work of the beatitudes to that of a plow in the fields. Drawn along with determination, it drives the sharp edge of the plowshare into the earth and carves out, as the poets say, a deep wound, a broad furrow…In the same way the word of the beatitudes penetrates us with the power of the Holy Spirit in order to break up our interior soil. It cuts through us with the sharp edge of trials and with the struggles it provokes. It overturns our ideas and projects, reverses the obvious, thwarts our desires, and bewilders us, leaving us poor and naked before God. All this, in order to prepare a place within us for the seed of new life.20

Now, to be honest, I always assumed that Jesus was being metaphorical or symbolic with the Beatitudes — that He was merely promising some kind of future happiness for those who aren’t all that happy in this life. But now I think He’s being more literal. To explain, let’s zero in on just one of the nine beatitudes: “Those who mourn.”

Paradoxical Blessing within Adversity

The psychologist William James has a saying that I initially found ridiculous: “The world is all the richer for having a devil in it, so long as we keep our foot upon his neck.”21

Obviously, the devil of Christian theology cannot cause anything good; but what he’s getting at is the reality that life is made more beautiful by its challenges.

The psychologist Susan Cain points out that negative emotions like sorrow and longing are what “make us whole.” It’s like that idea that those who don’t endure the lows of winter won’t experience the highest highs of summer, or that without the bitter the sweet isn’t as sweet.

Paradoxically, even though things like “mourning” don’t feel great in the moment, they often lead to comfort in the long run.

When we confront the reality of loss, suffering, or guilt head on, we learn to grow, change, and heal. “A person who sees things as they truly are and sympathizes with pain and sorrow is capable of touching life’s depths and finding authentic happiness.”22

In other words, it’s almost like Jesus said, “Happy is the one who confronts the sadnesses of life; for if they’d avoided them, they would’ve never stumbled into the comfort, consolation, and healing I offer.” Those who mourn are happier than those who distract themselves in blissful ignorance.

I experienced this truth when I was 18 and one of our close friends overdosed. Sadly, she didn’t make it. We’d just hung out with her the night before and heard the news at a tailgate the next morning. But rather than take time to process the emotion, I just kept drinking and partying. And there was nothing remotely “good” about how I felt the next day. I couldn’t look at a mirror because I reeked with a gross, disgusted annoyance with myself. When we sobered up and went to her funeral, I felt a pit of grief as we paid respects to her coffin. And contemplating her death made sobriety easier for awhile after that. I started following Jesus a month later.

Taking time to mourn is better than living in avoidance. Or, as Qoheleth put it, “It’s better to attend a funeral than a party” (Ecc. 7:2).

Interestingly, it turns out that humans actually need injections of negativity to experience richer lives. In six separate studies, psychologist Shigehiro Oishi and colleagues found that the happiest people didn’t just experience happy emotions the most strongly; the happiest people were those who experienced the whole spectrum of emotion more strongly—not just the feel-good ones.23

In one study, they asked a group to write about the two best things that happened to them that week. The other group was asked to write about the best and worst thing that happened to them that week. Surprisingly, the group that was asked to consider both the best and worst parts of their week reported more overall contentment.24

In the same way that emotions like envy or anxiety add drama to our movies, so negative emotions add texture and meaning to the fabric of our lives. We can only properly savor goodness when we have an opposite flavor to compare it to.

This isn’t to say that poverty and grief are aspirational; Jesus doesn’t want us to hope for our friends to pass away or finances to become scarce. He’s more so stressing the extremes or reaches of God’s generosity—that heaven’s availability becomes more pronounced in struggle, that everyone can receive it regardless of status, worth, circumstance, or ability.

There’s a superior overall happiness for those who are “sorrowful but always rejoicing,” than those who merely rejoice. Again, pain and suffering aren’t good things; but experiencing pain within a religious framework often reshapes our pain into something beautiful, meaningful, and rich.

Christians Are Allowed to Be Happy

The same general principle goes for every Beatitude. It’s better to “hunger and thirst for righteousness” than consider yourself self-sufficient. It’s better to receive “persecution for righteousness’ sake” than to stay silent in the face of evil, injustice, and wickedness.

We won’t live a rich life if “we are always looking to fit in, always seeking the approval of others, or always doing our best not to stir things up.”25 Taking Jesus’ Sermon seriously might leave us looking annoying, ridiculous, and out of touch with the reality; but maybe a life free of the social concerns of looking stupid while serving Jesus is precisely what a happy life looks like.

Put simply, “To live the Beatitudes is to live a happy and good life.”26 A life of meaning, growth, and love is a life of risk; but the risks are worth taking. A life apart from the adventure of God’s grand narrative ends up stale.

The Beatitudes, along with the rest of the lifestyle Jesus, inevitably drop us at happiness’ doorstep. As theologian Paul Wadell summarizes it, “Happiness characterizes the person who intentionally and consistently aspires to a life marked by humility, peacemaking, mercy, purity of heart, and securing justice for others. It is that kind of life—and not any other possible life—that offers a road map to happiness.”27

Since the Beatitudes open the Sermon, it’s almost like a disclaimer that the whole of the teaching invites its followers into what a happy, flourishing, and fortunate life really looks like.

But yes — it’s not conventional happiness. Jesus describes those who follow Him as traveling down a narrow way that few make it through (Matt. 7:13-14). Yet even though suffering is necessarily involved, the suffering never outweighs the joy promised to anyone who traverses His path. Paul says the sufferings aren’t even worth comparing with His glory (Rom. 8:18).

God didn’t create humans to suffer in solemnity, but to flourish through following His standards in the here and now. By becoming His children, He folds us into His family, along with all the joys and promises and blessings that come with it.28

The most shocking aspect of the Beatitudes is that they’re not just describing a future or post-mortem kind of happiness. The makarios is for those who follow Jesus right now. Perfect happiness might not come our way in this life, but the closest thing to it comes through His words.

Christian are allowed to be happy—the way to get there just might make us groan because it’s what we should’ve always expected. Happiness comes through pursuing Jesus. That’s all. There is no life hack or quick fix. The best method is simply the tried and true paradigm of losing our lives for His sake so that we might actually discover what life’s really all about.

Augustine, The Lord’s Sermon on the Mount, trans. John Jepson, S.S. (New York: Paulist Press, 1948), i.1.1.

Margaret Mitchell, “John Chrysostom,” in Jeffrey P. Greenman, Timothy Larsen, and Stephen R. Spencer, eds., The Sermon on the Mount through the Centuries: From the Early Church to John Paul II (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2007), 19-42.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae (New York: Benziger Bros, 1948), I–II, 108, 3.

For those that care, these will not be a systematic theological or biblical commentary string of posts. I’m aiming more toward creative personal reflection rather than scholarly exaction. But that said, I ascribe to a view of the sermon that does not see it as principally concerned with salvation or justification — even though that’s part of it. I believe it’s far more concerned about living a justified lifestyle within God’s already but not yet rule and reign (a la, McKnight, Mattison, Pinckaers, Pennington, Stassen, Mackie, and Willard).

See Dallas Willard’s exceptional work on “kingdom” in the first few chapters of The Divine Conspiracy.

The “Sermon on the Mount” is more recent title — borrowed from Augustine’s commentary on the Sermon in the 5th century.

Robert Louis Wilken argues that ancient Greek usage of eudaimonia and makarios were so similar that they were by and large used interchangeably. “Gregory of Nyssa, De Beatitudinibus, Oratio VIII: ‘Blessed are Those Who Are Persecuted for Righteousness’ Sake, for Theirs Is the Kingdom of Heaven (Mt 5,10),” in Drobner and Viciano ed(s). Gregory of Nyssa: Homilies on the Beatitudes (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 244–245. See also Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, ed. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1999), 318.

This sort of “God-given blessing” idea is what lurks behind the Hebrew term bārûk, but not necessarily ʾašrê. See Jonathan Pennington, The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2017), Ch. 2.

Jeong-Kyu Lee, “Christianity and Happiness: A Perspective of Higher Education,” Academic Paper, 2020, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED607132.pdf.

Makarios had many possible connotations: the happiness of the gods, the happiness of life after death, the happiness of a wealthy or famous lifestyle, and the happiness of righteousness. See throughout Lee, “Christianity and Happiness.” Interestingly, the Greeks of the day usually used the eudaimon for happiness, which referred to a kind of happiness that came from one’s own responsibility or power. Conversely, the biblical authors never used eudaimon, but only makarios, which refers to a happiness bestowed by God. See Merwe, Johannes, “Biblical Happiness and Baptismal Identity,” 695-710.

Van der Merwe and Izak Johannes, “Biblical Happiness and Baptismal Identity,” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1 no. 2 (2015): 695-710.

See Robert Guelich, The Sermon on the Mount: A Foundation for Understanding (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1982), 66; Hans Dieter Betz, The Sermon on the Mount (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1995) 92.

It’s SUPER rare to find any one-to-one translations within the Masoretic Text and Septuagint, but this is one case where it’s a surprisingly exact substitution of terms. Pennington, Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing, Ch, 2.

See Plato’s Republic (Book IV: 436a–444e; Book VI: 485a–487a; Book IX: 580d–592a) and just about all of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

Scot McKnight, The Sermon on the Mount, The Story of God Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2013), 32.

Servais Pinckaers, The Sources of Christian Ethics, trans. Mary Thomas Noble (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1995), 150; Pennington, The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing, 36.

Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary, Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 257.

R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 193.

Søren Kierkegaard, Christian Discourses, ed. and trans. Howard Hong and Edna Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 222.

Servais Pinckaers, Pursuit of Happiness (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2011), 36-37.

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study on Human Nature (New York: Longmans Green, 1902), 50.

Pope Francis, Rejoice and Be Glad: Gaudete et Exsultate (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018), #76; quoted in Paul J. Wadell, Happiness and the Christian Moral Life: An Introduction to Christian Ethics (Lanham, MY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 4th edn., 2024), 10.

Shigehiro Oishi, Life in Three Dimensions: How Curiosity, Exploration, and Experience Make a Fuller, Better Life (New York: Doubleday, 2025), 51.

Oishi, Life in Three Dimensions, 52.

Wadell, Happiness, 11.

Wadell, Happiness, 5.

Wadell, Happiness, 6.

Katherine J. Schori, “The Pursuit of Happiness in the Christian Tradition: Goal and Journey,” Journal of Law and Religion 29 no. 1 (2014): 57-66.

Great topic! Always love chanting the beatitudes at church every Sunday - such a powerful reminder of kingdom virtues and what it means to flourish.

I have in the past struggled with the “blessed are the meek” one as it sounded like “weak and mild vibes”, but I read somewhere that it actually refers to “having power which is exercised with wisdom and restraint”, which makes more sense for me now.

“In other words, it’s almost like Jesus said, “Happy is the one who confronts the sadnesses of life; for if they’d avoided them, they would’ve never stumbled into the comfort, consolation, and healing I offer.” Those who mourn are happier than those who distract themselves in blissful ignorance.” Oof. Just wow.

Griffin, this is amazing. It sounds weird to say but thank you for reminding us we have permission as Christians to be happy! And that happiness can be part of our lives now as Christ followers, even through the pain and longing of it all. That reminds me of a lecture I heard this summer on theosis from Myk Habets. So much of what you wrote here reminds me of truths he shared, too.