What's the Point of Prayer?

Unanswered Prayer, the Importance of Persistence, and Why Prayer Changes More Than Your Emotional State

Audio voiceover for paid subscribers available here!

I asked for prayer every day for a year and never got any healing.

I strained my vocal cords beyond repair while working as a worship leader – problematic, cause of the required vocals. So I started asking my friends and roommates to pray for healing every day. During each week’s post-sermon altar call, I’d make a beeline toward the prayer team and ask the same. I even attended the hyper-Pentecostal One Thing conference — a gathering of 10,000 Christians charismatic enough to casually initiate exorcisms, the cinematic kind with lots of spasms and moaning — and asked for prayer constantly. No healing came.

For a while, not understanding why crippled me. I couldn’t wrap my mind around why God wouldn’t answer a prayer that so clearly seemed to align with His will.

But years later, it made sense.

—

Unanswered prayer is one of the great philosophical questions in the Christian life. We’re told that Jesus will do anything “we ask according to His name” and that “if we have faith and no doubt,” our prayers can literally move mountains (John 14:13; Matt. 21:21-22). And yet, the imagined outcome of many of our prayers never seem to materialize.

Even beyond unanswered prayer, the act of prayer itself — asking a perfect God to do stuff that a God who’s actually perfect would presumably want to do anyways — is a bit confusing.

So the following is a summary of how I’ve tried to make sense of prayer. It started out as a long Google doc where I’d wrestle with why prayer matters, and it ended with my becoming more convinced than ever that prayer is the most significant thing we could do with our time at any given moment.

I don’t think I’ve cracked the code — it’s a working theory that still needs work. Yet for where I’m at right now, it’s exactly what I needed. And maybe it’ll help you too.

First, let’s run through some common concerns with prayer, starting with the idea that

prayer changes you, not reality.

Søren Kierkegaard famously said, “Prayer does not change God, but it changes the one who offers it.”1

This view — that prayer’s purpose is to change your emotional response to situations rather than the situations themselves — is common among strands of the contemplative tradition, the spiritual formation movement, and, for whatever reason, academics.

There’s a kernel of truth to it. Theologian Georgia Harkness called prayer the process where fruits of the Spirit “become operative in our lives.”2 Or, as Paul wrote, as we “let our requests be made known to God,” “the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard our hearts and minds” (Phil. 4:6-7).

And prayer really does change the pray-er.3 Dozens of studies have documented the emotional benefits of prayer.4 For example, in psychologist Frank Fincham and colleagues’ study, they split up couples into two groups and asked the first group to carry on business as usual and the second group to pray for the well-being of their partner every day. At the end of the study, those in the second group were less likely to have considered infidelity, were more satisfied with their relationship, and even felt that their bond was more sacred or holy.5

So prayer does change us; of course it does. But the idea that prayer only changes our interior and doesn’t move God’s heart to interact with the exterior does not align with biblical theology. Scripture reveals a God who’s “moved by prayer” (2 Sam. 24:25), who often “relents” when His imagers repent or ask for mercy (Exod. 32:14; Jonah 3:9-10; Joel 2:13-14).

As the NT scholar David Crump put it, “Prayer can and does move God; it makes a difference. Some things in life occur, at least in part, because God’s people asked him to act accordingly (2 Cor. 1:11; Phil. 1:19; Philem. 22).”6 We can dart around it all we want, but it’s hard to affirm a plain reading of the Bible while also believing that God doesn’t hear and respond to prayers (Jer. 29:12; Luke 18:1-8).7

In Karl Barth’s words, “God answers. God is not deaf, but listens; more than that, he acts. God does not act in the same way whether we pray or not. Prayer exerts an influence upon God's action.”8

I think one reason people tend to minimize prayer to self-renovation is because

petitionary prayer makes theology kinda hard to understand.

While philosophers like Plato and Aristotle used logic to decide that it was impossible to influence God through prayer,9 theologians who hold the Bible over logic must come to terms with a God who seems remarkably concerned with everything happening on earth, from singular human hearts to the hairs on their head to every sparrow that falls to the ground (Matt. 10:29-30).10

As the theologian Paul Copan put it, God “isn’t the static, untouchable deity commonly associated with traditional Greek philosophy. He’s a prayer-answering, history-engaging God.”11 While the God of pure philosophy doesn’t hear prayer because logic doesn’t permit, the God of the Bible hears prayer regardless of logic — almost as if He’s breaking the metaphysical status quo just to hear our heart’s cry.12

And honestly, it’d make more sense from a rationalistic, logical standpoint if God was just a divine clockmaker who set the earth into motion and then took His hands off. That kind of God is easier to grasp theologically. But the fact that God actually responds to human prayer throws a wrench in the system.

To illustrate, take theologian John C Peckham’s observations about prayer:

Whatever else we say about prayer, this much is evident:

1. God needs no information.

2. God needs no power.

3. God need not be convinced to do what is good.

Nevertheless,

1. God invites petitionary prayer.

2. God responds to petitionary prayer.

3. God is depicted as if petitionary prayer actually influences him.13

I think these paradoxes are why those who spend so much time pondering theology often conclude that God probably isn’t listening: the more we think about prayer, the less it seems makes sense.

But at the same time, part of the wonder behind prayer is the way we can’t figure it out perfectly; its contradictions add to its beauty and mystery.

Anyways, if we accept that prayer actually influences God to act in ways He otherwise wouldn’t, we have to tackle what Peckham calls

“The Influence-Aim Problem.”

Basically, this is the problem of how to make sense of a God who’s

(1) all-knowing (omniscient),

(2) all-good (omnibenevolent),

(3) all-powerful (omnipotent), and yet also believe that

(4) our prayers might influence this God to bring about some good that he otherwise wouldn’t bring about.14

In other words, if God really knows the best possible good for every possible circumstance, prefers to bring that good about, and has more than enough power to do so, then why would prayers from finite, limited, and flawed humans matter?

And if God really is good, then isn’t withholding good things from people unless they remember to ask technically not good? Especially if we frame this in terms of basic needs like food and water, why would a good and powerful God not supply those things? Wouldn’t His lack of automatic provision contradict His own character?

To help make sense of this, we need to bring

free will

into the picture.

(Calvinists, now’s the time to play this clip):

What if God wants to do good, but there are certain factors God’s set in place that morally prevent Him from bringing about the good He’d prefer to bring about? And what if our prayers, inspired by our freedom to choose good instead of evil, inspire God to push in those good directions?

As the scholar W. Paul Frank suggests, maybe “God has restricted his powers of interaction with humankind in such a way that those powers are exercised only in response to promptings from humankind.”15

In other words, if God never lies (1 Tim. 1:2) or breaks a promise (Heb. 6:18), then He’s morally bound to honor whatever He commits to. So if God commits to allow humans freedom of choice, then even though this commitment doesn’t literally limit His omnipotence, it morally limits the ways He’s able to exercise His power because it puts any action that would contradict His commitments off limits.16

Just think about this bit in Jesus’ Gethsemane prayer: “My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me” (Matt. 26:39). How does this make sense with Jesus’ other statement, “all things are possible for God” (Mark 14:36)? Chances are, it’s because even though all things are possible to God, there are certain things that are off limits simply because doing those certain things would contradict God’s own character.

If we follow this thought, we can retain a view of God being all-powerful and all-just, since it’s more of a “self-imposed restriction” put in place for the sake of inviting human imagers into His divine processes.17

Which also illuminates the “why” behind His self-limiting. In order for this all to align with God’s ultimate character, He must have gifted us this free will for a purpose that’s ultimately worth it: aka, love – and more of it.

As C.S. Lewis put it,

Free will, though it makes evil possible, is also the only thing that makes possible any love or goodness or joy worth having. A world of automata — of creatures that worked like machines — would hardly be worth having. The happiness which God designs for His higher creatures is the happiness of being freely, voluntarily united to Him and to each other…And for that they must be free.18

Okay that was a lot, but basically: for love’s sake, God might limit His own actions. This limiting then creates the possibility — or perhaps inevitability — of the Spirit placing what to pray for on our hearts (Rom. 8:26) in order to bring about some higher good.

But free will doesn’t resolve every question. What if the free will prayers of one person contradicts the free will prayers of someone else? Does God have to take the prayers of a righteous farmer praying for rain more seriously than a slightly less righteous ship captain praying for calm weather? And how do we make sense of seemingly unanswered free will prayers?

This is where we have to talk about the

cosmic conflict

stuff.

Feel how you’d like to feel about a cosmic war between light and darkness, angels and demons, powers and principalities, backgrounding every aspect of our universe, but this was an uncontroversial reality for the authors of the Bible (see Matt. 4, 12:24, 13:24-39, 25:41; Eph. 6:11-12; Col. 1:16-17; 2 Pet. 2:4; Jude 6; Rev. 12:7-10).

According to Luke, John, and Paul’s theology, the devil actually has jurisdiction over this world (Luke 4:6; John 19:11; 2 Cor. 4:4). In Lewis’ words, “There is no uncontested territory in our universe,”19 and we’re currently “living in the part that is occupied by the rebel.”20

Yet despite that the “whole world lies under the power of the evil one” (1 John 5:19), this power is both limited and temporary (John 12:31; 14:30; 16:11) and God still ultimately decides the rules.

The best example we have of how this works practically is Job 1-2, where God grants Satan permission to antagonize Job. Satan wants to show that Job’s love for God is only as deep as his material blessings, so God allows Satan to run a test—not on a whim or for the sake of using Job like a punching bag, but so that God can prove Satan wrong, Job righteous, and demonstrate His own glory (Job 1:20-2:10).

But in general, this cosmic conflict is

less about power, more about truth.

This war isn’t about God struggling to have more power than the devil. Instead, the struggle is about one of the few areas God likely doesn’t have control over: the way folks with free will use that free will to understand truth.

This is why the devil so often tries to convince people to believe untrue things about God. Just think of the serpent convincing Eve that God didn’t want what was best for her (Gen 3:1-6) or John’s depiction of demonic powers accusing God all “day and night” (Rev. 12:9-10) or any other example (see Zech. 3:1-3; Job 1-2; Matt. 13:27-29; John 8:44; Rom. 3:3-8, 25-26; 2 Cor. 11:3; Jude 9; Rev.13:4-6).

To illustrate why untruth is corrosive, just think of it in terms of a marriage.21 Imagine someone told you your spouse was cheating on you. Whether or not there was evidence, even the slightest suspicion that it could be true would hurt your relationship. You’d get paranoid or angry or fearful. Similarly, if we have a suspicion that God isn’t fully good, loving, or joyful, our trust in Him disintegrates.

So basically, the father of lies’ strategy is weaponizing our perceptions of God, and our heavenly Father’s strategy is the opposite: transforming disinformation into pathways toward His eternal truths. Maybe this is why one of the most common features of prayer throughout both testaments are reminders of God’s character; it’s like they’re saying, “We know who You are; show everyone these allegations are false.”

Anyways,

this invisible battle between good and evil is why our prayers matter.

Our prayers help expand the avenues of action that are morally available to God. It’s like they invite Him to do things He was hoping to do but waiting for our prayers to help un-obstruct the things blocking that route of action.22

Take Daniel’s prayers for example. He prays for divine intervention (Dan. 9-10:9) but doesn’t hear an answer for three weeks. When an angel appears, he says “your words have been heard” “from the first day you set your heart to understand and humbled yourself before God” (Dan. 10:12). But “the Prince of the kingdom of Persia” (i.e., a divine principality) “withstood me for twenty-one days” (Dan. 10:13).

OT scholar Tremper Longman III calls this passage a “clear case of spiritual conflict…Even though the divine realm heard and began responding immediately to Daniel’s prayers three weeks earlier, there was a delay because of a conflict, an obstacle in the form of this prince of the Persian kingdom.”23

This is similar to Paul’s point when he wrote that he wanted to visit the Thessalonians, “but Satan blocked our way” (1 Thess. 2:18), or Jesus’ words to Peter in Luke 22:31-32: “Satan demanded to have you…But I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail.”

It’s like the cosmic conflict is fought over potential futures, and our prayers either

(1) help close off potentially worse futures and/or

(2) open up potentially brighter ones.

Just consider these

examples:

when God tells Abraham about His plans to destroy Sodom, Abraham appeals to God’s mercy, and God listens (Gen. 18:23-32).

Then when Hagar and Ishmael ran out of water in the wilderness, she cried out and God preserved them (Gen. 21:16-18).

Later, Moses asks God to avert His judgement and “remember” His covenant promises, worrying that surrounding nations would see God’s wrath and doubt God’s character (Ex. 32-33). So God relents.

Years later, when the barren Hannah “prayed to the LORD and wept bitterly,” God listened and granted her a son (1 Sam. 1:10-27).

After that, Solomon prays and God sends fire down and “the glory of the LORD fills the temple” (2 Chron. 7:1). God then appears to Solomon and tells him that if His people humble themselves and pray, He’ll intervene and “heal their land” (2 Chron. 7:12-14).

Way later, Peter prays in a jail cell and the chains literally fall off of him and he leaves (Acts 12:5-17).

These snippets show a God who seems to welcome our prayers in a way that affords us actual agency in paving brighter futures. For some reason, God seems to “work out his purposes in cooperation with his children”24 – almost like a partnership.

We’re not equal partners (not even close). But the way we pray does influence Him – whether or not we prefer to use this language.

But on that note, it’s time to

cover my bases so the theo bros don’t come after me.

This theory doesn’t imply that humans are on the same plane of causality as God or that God’s not sovereign or in control.

(Arminianists, now’s the time to play this clip:)

All it has to imply is that God allows us to at least feel like we’re partnering with Him and that our prayers play a role in His plan (2 Chron. 7:12-14; 2 Cor. 6:1).

Further, this doesn’t imply that our prayers change God. We don’t have to surrender our doctrine on God’s immutability (unchanging-ness) and impassability (the inability to be affected by emotion).

Instead, we can think of it in terms of God simply working in stride with the way that we ourselves move and change and act. As Peter Baelz puts it, “God’s love is perfect and unchanging; but the created objects of his love, and consequently his relations to them, do change.”25 In other words, we change. God doesn’t.

Okay back to the initial question:

what do we do with unanswered prayers?

We’ve all experienced unanswered prayer to some extent. Maybe you’ve been praying for years and still don’t see a clear answer. The felt absence of response brings on a flood of emotion: confusion, anxieties that we didn’t pray hard enough, shame that maybe some sin caused God to stop listening to us, or fears that prayer simply doesn’t work.

Like Georgia Harkness described it, “Most of the bitterness of unanswered prayer comes from the assumption that God will juggle his universe to give us what we plead for if we plead long enough.”26

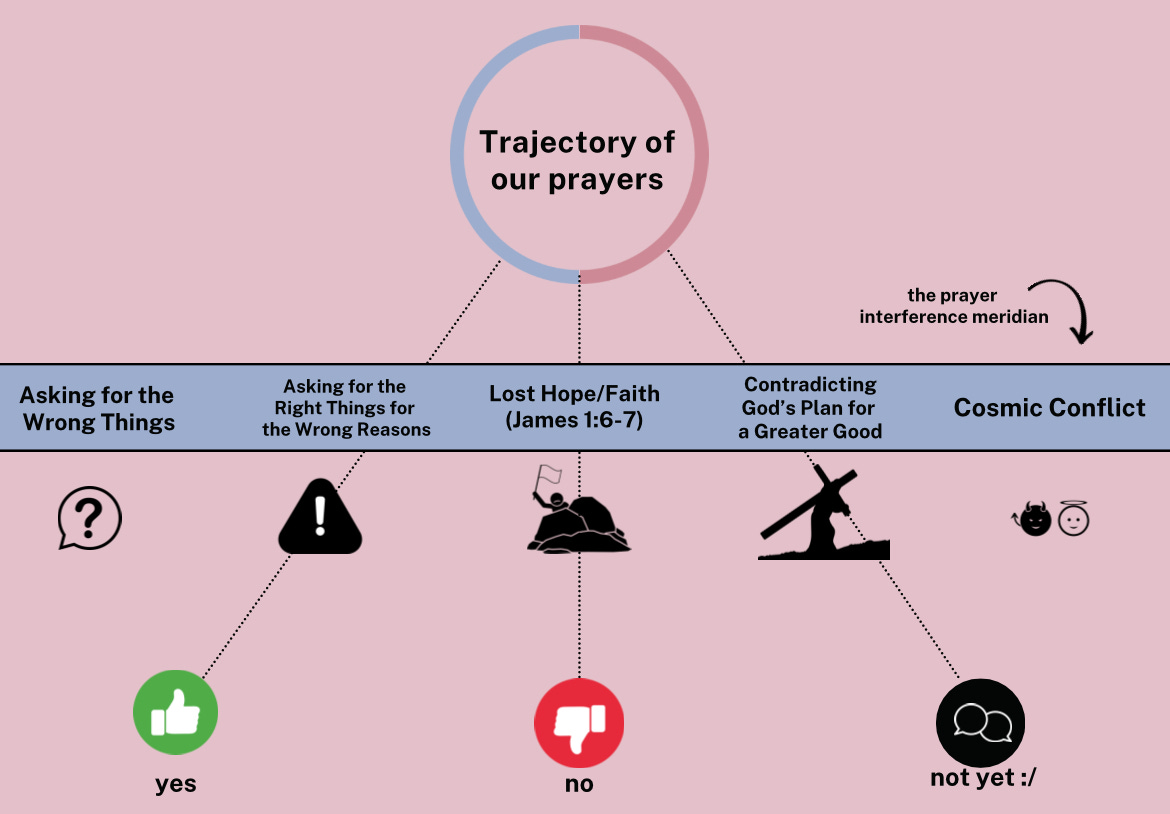

However, following the line of reasoning we’ve talked about so far, if our prayer isn’t answered, this doesn’t that prayer doesn’t work. Instead, it might mean:

1. We were praying for the wrong things.

2. We were praying for the right things with the wrong motives (see Js. 4:2-3; Rom. 8:26; 1 John 5:14-15).

3. We lost hope that God could even theoretically answer our prayers (Js. 1:6-7).27

4. Our prayers might’ve contradicted God’s plan to bring about some greater good.

5. Some unseen demonic forces or free will agents obstructed our prayers.

Now, this might come across discouraging – as if there’s so much potential interference to our prayers that there’s no point in even giving it a shot. But not praying out of a sense of futility is the opposite of a solution.

I wonder if the human tendency to get discouraged in prayer is why Jesus was so adamant about persistence. Like the widow who continually approaches the judge or the shameless neighbor knocking on their friend’s door after hours, so we too “ought always to pray and not lose heart” (Luke 18:1).

Persistence doesn’t mean that God requires simple repetition, as if He’ll eventually say “uncle” around the 10th recitation. Instead, it’s more likely emphasizing the steady, unashamed faith that comes from continually believing that God can and wants to do good things in our lives. God hears our prayers even if we only ever pray it once; but a persistent posture of faith may go a longer way in chipping away the powers of darkness than a half-hearted utterance muttered in doubt (Luke 18:7-8).

Crump encourages pray-ers “to remember that while our prayers may appear to be in vain,” we “wait because of God’s timing, not because of God’s neglect.” He hears every prayer and “rules justly,” but His “timing remains mysteriously his own.”28

Unanswered prayer is one of the loneliest sensations. But this loneliness is yet another one of the messy feelings we should intersplice into our communion with God. In prayer, honesty really seems to be the best policy.

We may pray so hard that we cry and convulse; we might feel like God’s abandoned us, like we’re a parched deer looking for water but unable to find any. Like Hannah, prayer might be where we experience our apex of “bitterness,” “distress,” or “affliction” (1 Sam. 10-11). But these emotions are a normal part of prayer (see the Psalms). Our anger or loneliness isn’t a sign that we’ve lost trust in God, but that we’re properly wrestling with Him and the strange tensions of living in an imperfect present age.

Okay, time for

closing thoughts.

There are many reasons to pray, but petition is the foremost. Even Thomas Merton, the monk who famously popularized meditative forms of prayer in the West, warned contemplative types to keep up their petitionary prayer because petition is the most biblical form of prayer.

Whatever else we say about prayer, we can make these conclusions:

(1) God invites prayers from us,

(2) He’s willing to bless us,

(3) He already understands our hearts (2 Chron. 6:30) and yet desires our prayers as a way to showcase His glory,

(4) He seems to give priority treatment to humble and repentant prayers,

(5) even though He might not answer prayers the way we think He should, He’s intimately concerned with justice — even considering our flawed visions of justice worth hearing out;

(6) God welcomes honest questions, with our sloppy emotions and all.29

But for times when we still get discouraged or lose heart, I find Philip Yancey’s words comforting:

When doubts creep in and I wonder whether prayer is a sanctified form of talking to myself, I remind myself that the Son of God, who had spoken worlds into being and sustains all that exists, felt a compelling need to pray. He prayed as if it made a difference, as if the time he devoted to prayer mattered every bit as much as the time he devoted to caring for people.30

God always hears our prayers, our groanings, our cries for help. He can’t not feel moved by them. If we aren’t getting the answers we’re hoping for, it’s not because of His lack of care, but likely for some reason that transcends our comprehension.

—

To circle back around to the beginning, if God had answered my prayers for healing, I would’ve never started writing. I would’ve never gone back to school. I would’ve never done much teaching or mentoring. And each and every one of those things makes me feel more alive than worship leading ever did.

But even more than all that, if God had granted my prayers in the way I’d wanted Him to, I would’ve never met my wife. I would’ve missed the chance to get to know my best friend and build a solid relationship with my father. I would’ve never connected with my church.

I’d rather have my vocal cords strained 10 times over than not experience any one of those things. God used something bad for an unparalleled good.

Finally, I’ll end on these words from Peckham:

“If we could see the end from the beginning, we might frequently find reasons to pray, ‘Thank you, God, for not giving me what I asked for.’”31

Amen.

Søren Kierkegaard, Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing: Spiritual Preparation for the Office of Confession, trans. Douglas V. Steere (New York: Harper & Row, 1956), 51.

Georgia Harkness, The Recovery of Ideals (New York: Scribner’s, 1937), 73.

Scott A. Davison, God and Prayer, Elements in the Philosophy of Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 3.

See for example Kathleen C. McCulloch & Elizabeth J. Parks-Stamm, “Reaching Resolution: The Effect of Prayer on Psychological Perspective and Emotional Acceptance,” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12, no. 2 (2018): 254–263; Ying Chen & Tyler J VanderWeele, “Associations of Religious Upbringing With Subsequent Health and Well-Being From Adolescence to Young Adulthood: An Outcome-Wide Analysis,” American Journal of Epidemiology 187 no. 11 (2018): 2355–2364.

Frank Fincham, Nathaniel Lambert, & Steven Beach, “Faith and Unfaithfulness: Can Praying for Your Partner Reduce Infidelity?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99 no. 4 (2010): 649-659.

David Crump, Knocking on Heaven’s Door: A New Testament Theology of Petitionary Prayer (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006), 228.

For a more thorough take on what I mean by “plain sense,” see Kevin Vanhoozer, Mere Christian Hermeneutics: Transfiguring What It Means to Read the Bible Theologically (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2024), 119-121.

Karl Barth, Prayer, trans. Sara F. Terrien, Don E. Saliers, ed(s). (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2002), 13.

This is an oversimplification, but many philosophers in the Aristotelian and platonic tradition did certainly hold to a strict classical theistic orientation in which God was immovable and impassable. And yes, the “God” they were considering was mostly a vague deity and not specifically the Judeo-Christian God – though there’s debate about this in Plato’s later work like Timaeus.

See Emil Brunner, The Christian Doctrine of God, Vol. 1 of Dogmatics, trans. Olive Wyon (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster, 1950), 269.

Paul Copan, Loving Wisdom: A Guide to Philosophy and Christian Faith (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2nd edn., 2020), 94.

Michael Horton, Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 240.

John C. Peckham, Why We Pay: Understanding Prayer in the Context of Cosmic Conflict (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2024), 50. Giving this book a shoutout at the beginning was not false humility. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that so clearly argued for why prayer matters. Almost everything in this article was inspired by this book.

Peckham, Why We Pray, 10.

W. Paul Franks, “Why a Believer Could Believe That God Answers Prayer,” Sophia 48, no. 3 (2009): 319–324 (at 322).

For more on this, see John C. Peckham, Theodicy of Love: Cosmic Conflict and the Problem of Evil (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2018).

Peckham, Why We Pray, 16; see also Peter Baelz, Prayer and Providence (London: SCM, 1968), 115

Always nice when you can find a C.S. Lewis quote to support your argument because, for many Christians, he’s basically authoritative. C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 48.

C. S. Lewis, “Christianity and Culture,” in Christian Reflections, Walter Hooper, ed(s). (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1967), 168.

Lewis, Mere Christianity, 45.

Peckham, Why We Pray, 71.

Peckham, Why We Pray, 18.

Tremper Longman III, Daniel (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1999), 249.

Patrick D. Miller, They Cried to the Lord: The Form and Theology of Biblical Prayer (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1994), 268, 269; Peckham, Why We Pray, 46; Donald Bloesch, Struggle of Prayer (San Fransico, CA: Harper & Row, 1980), 55, 75.

Baelz, Prayer and Providence, 39.

Georgia Harkness, Prayer and the Common Life (New York: Abingdon-Cokesbury,1948), 36.

Also Peter notes that husbands must “show consideration to” and “honor” their wives so that “nothing may hinder their prayers” (1 Pet. 3:7). This might mean that certain mental, emotional, or spiritual dispositions might hinder our prayers. Even further, James 5:16 states that the “prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective,” which further builds a case in the power of prayers from a humble, morally righteous disposition.

Crump, Knocking on Heaven’s Door, 105.

Peckham, Why We Pray, 26, 35.

Philip Yancey, Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference? (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2006), 79.

Peckham, Why We Pray, 132.

Your wrestling with unanswered prayer reveals a profound truth: Christ’s incarnation hallows human weakness as a sacrament of divine encounter. When Paul pleaded for his thorn to be removed, Christ didn’t heal him but joined him in suffering. "My power is made perfect in weakness". Your strained vocal cords may be less a denied petition than an invitation into the logos of the Cross, where God transfigures brokenness into communion.

The mystics show us that unanswered prayers often carve out hollow spaces for the divine indwelling, like Julian of Norwich’s wound that became a window to revelation. Your healing was not withheld as much as it was transposed into a deeper key. What the Pentecostal prayer lines could not restore, God has reshaped into a new mode of bearing witness. Not through song but through the vulnerable testimony of a life that still praises when the music stops. This is the economy of incarnation: our unmet longings become the very place where we discover prayer is not about changing God’s mind but about having our humanity fully assumed into His.

Jesus says multiple times, in every Gospel: 'ask for anything in my name and I will give it to you.'

I believe this and take it literally.

I absolutely believe that God answers every prayer, and the answer to every prayer is 'YES'.

and ...

- we don't always know what we're asking for

- we don't always recognize 'yes' when we get it

- we understand things on our timeline, not God's

- we live in a world mitigated by sin (ie not everyone is praying for good things...)

- we live in a world with billions of people, uncountable prayers, some of them contradictory (ie our prayers are not in isolation)

The result is the world we live in: unfathomable beauty along with terrible chaos. Answered prayers we most certainly see, and those being answered that we will only understand as the world continues to be reconciled by God.