Why Achievement Doesn't Make Us Happy

Career Dysmorphia, Miroslav Volf's The Cost of Ambition, and Comprehending the Beauty of Our Strange, Surrogate Family

Audio voiceover available for paid subscribers here!

1. Career Dysmorphia

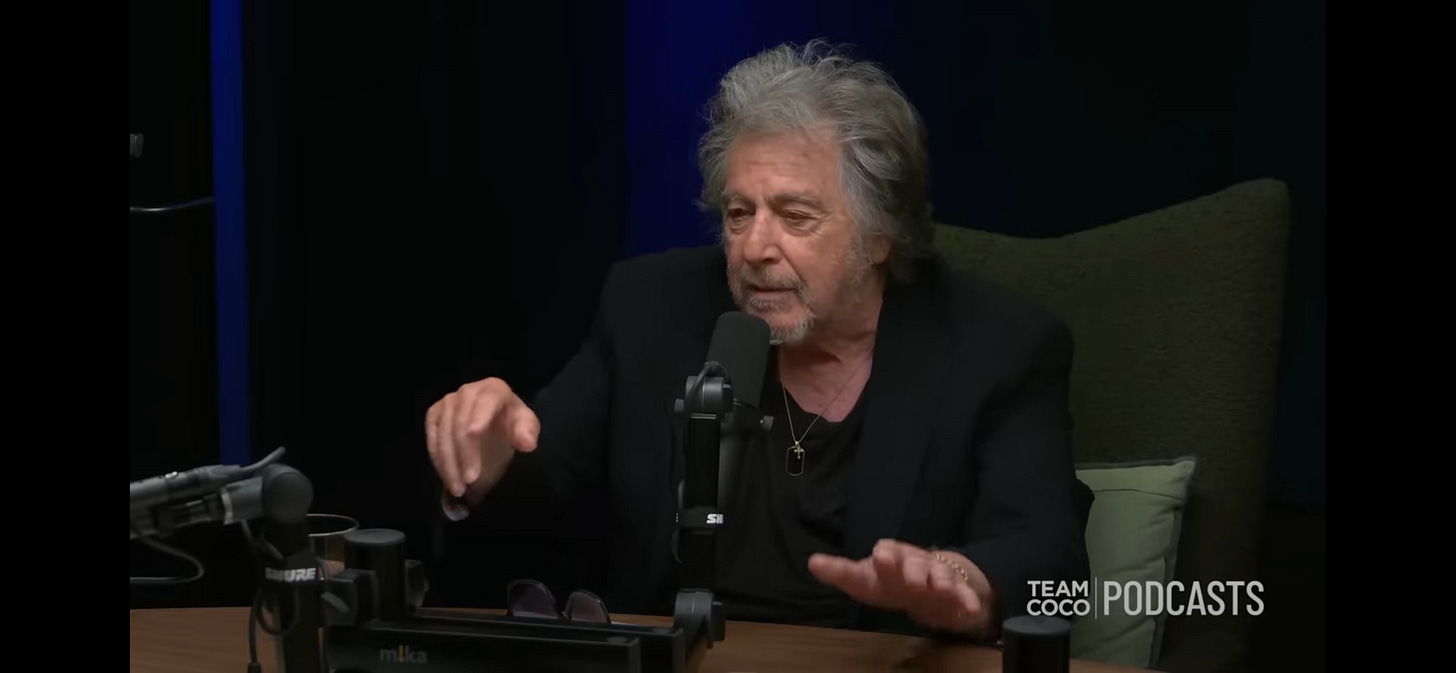

After interviewing Al Pacino, comedian Conan O’Brien dreamed up a new disorder for the next DSM.

Despite a successful career spanning over five decades, Pacino admitted that he rarely felt like he’d “made it.” In his own mind, his status as an actor was always in flux. If he didn’t have a prominent role in a film every few years, he’d feel washed up.

Which is a ludicrous thing to come from the mouth of the lead of the first two Godfathers. Ludicrous enough that O’Brien recommended that medical professionals study “career dysmorphia.”

In the same way that impossibly fit people might suffer from unrealistic perceptions of their own bodies, so esteemed actors, musicians, and entrepreneurs struggle with unrealistic perceptions of their own accomplishments. It’s similar to what Harvard Professor Arthur Brooks calls the “Striver’s Curse” – a nearly universal inferiority complex felt among those who pursue achievement in their careers.

After Brooks compiled hundreds of interviews and extensive studies of some of the more influential characters in history, he arrived at this conclusion: the harder people strive toward achievement, the more paranoia they’ll feel about how those achievements measure up to everyone else’s — and the more they’ll fear their career’s inevitable decline.1

This doesn’t just impact celebrities pining for Best Actor or Zuckerberg and Bezos vying for world domination. In fact, anyone who’s intent on striving for greatness in their field probably struggles with this to one degree or another. There’s always another hill to climb, another milestone to cross, another critic to prove wrong.

2. It’s Because We’re Playing the Status Game

“Even if all actors received the same salary, a man would rather act the part of Hamlet than that of the First Sailor.” – Bertrand Russell

The hunt for higher status than whoever’s standing next to us isn’t just an awkward mental appendage reserved for social climbers. Unfortunately, it’s a feature that defines culture – especially the modern kind of culture.2

It litters sports (both on the field and through fans living vicariously through their teams), politics (almost more so through radical voters than between actual candidates), and education (as the horrendous anxiety and depression levels amongst high-achieving high schools attest).3

But it extends well beyond the obvious examples. Indie kids often sort people into a hierarchy of coolness based on their music tastes. Others might use clothes as a makeshift Rorschach test, ranking people into specific cliques and tiers of popularity. You can engineer almost any quality into a status signal.

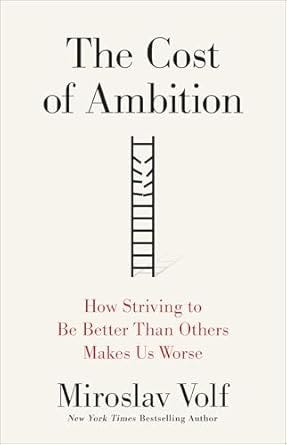

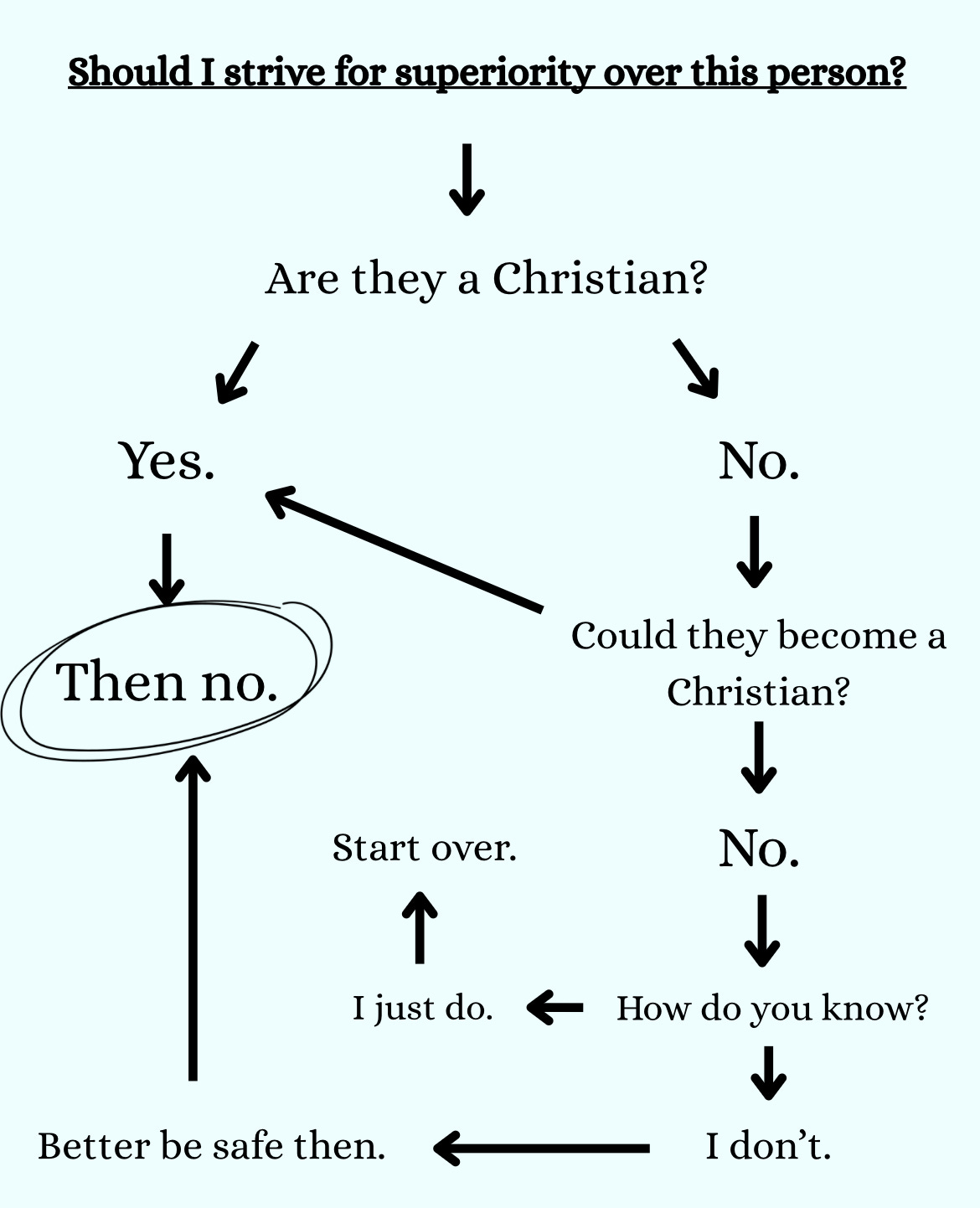

In theologian Miroslav Volf’s The Cost of Ambition (which is shaping up to be my favorite book of the year), the Yale professor offers a deep dive into this obsession with status, which he calls “striving for superiority.”

This striving is like a constant, involuntary monitoring system that tracks how we measure up to others. On one hand, it anxiously pursues the “short-lived” euphoria of finding ourselves above whichever rivals feel relevant at the given moment.4 On the other, it avoids humiliation with the zeal of a PR manager avoiding their client getting cancelled.

This striving is “literally everywhere” – even extending into the realms of the straight up ridiculous. I know a theologian who admitted he unconsciously felt superior to his colleague simply because his office was closer to the parking lot. I’ve heard some of my Bible college students discuss how “Ring before spring” can feel like a competition of who can receive the quickest and most elaborate engagement.

Sometimes I notice I feel briefly superior to someone who takes the elevator while I take the stairs, or when I stand next to someone and realize I’m taller (which, at 6’5, thankfully provides a steady stream of wins). It’s almost like we come with an inner hoarder obsessed with coming on top in thousands of microscopic ways.

Yet, striving for superiority isn’t just a different shade of classical sins like envy or pride.5 In fact, it’s almost like a midpoint between the two, frankensteining the worst parts of each into a mess of egoistic exhaustion. The striving is less about feeling good about ourselves than it’s about offloading “the pain of inferiority onto another.”6

And if we don’t feel successful in one arena, we jump to another. For example, a pastor might look at another pastor who runs a bigger church and think, “My church isn’t as big, but that’s because I’m more virtuous than that pastor. Like Jesus said, ‘Woe to you when all people speak well of you.’”

Yet, despite how striving creeps into every corner of life, there are few things people are more uncomfortable discussing. The novelist Tom Wolfe called status the “fundamental taboo, more so than sexuality and everything of that sort. It's much easier for people to talk about their sex lives than to talk about their status.”7 Especially in Christian community, where we’re supposed to “become less as He becomes more,” status striving feels gross to admit.

But it’s nowhere near as strange as it’s made out to be. After studying social striving in human cultures, anthropologist Edmund Leach concluded that people crave status because they crave security.8 In other words, they want to feel wanted, needed, valuable. So in its most basic form, this striving is really just a desire to belong – to have our emotional needs validated through connecting with others.

Unfortunately, this makes it tricky to tell where the basic human striving for belonging crosses into neurotic ego-building territory. But, in short, the best gauge is simply self-consciousness – or the lack thereof. To explain, Volf draws on a helpful distinction from the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who described two forms of self-love: amour de soimême and amour propre.9

The first is un-self-conscious and primal: it’s the drive toward self-preservation that reminds us to eat and brush our teeth and get eight hours of sleep and stay in touch with friends and family.

Conversely, amour propre is entirely self-conscious. It’s the kind of self-love that causes vanity. In classical terms, you’d call it “vainglory” (i.e., “anxiety over one’s reputation”).

Amour propre is what kindles those intrusive thoughts about our relative social standing. It famously tortured Blaise Pascal, who said it made him feel like his own status was taking God’s place in the throne of his heart.10

Even though the competitiveness it provokes can spark innovation, amour propre’s negatives outweigh its positives; like Rousseau said, the end result is “a multitude of bad things and a small number of good.”11 We see this in the Hamilton-esque archetypes who strive for greatness non-stop, crunching away at the office or studio or stock trade until they’ve alienated friends and family.

And the saddest part is that these strivers usually end up more dissatisfied toward the end of their careers than at the start.12 Someone who’s obsessed with their status is “always outside himself, is capable of living only in the opinion of others and derives the sentiment of his own existence solely from their judgment.”13

This is right about where Volf’s book hit home for me.

3. You & Me & Social Superiority

Writers often use writing as a way to work their stuff out. It’s why Joan Didion wrote A Year of Magical Thinking after her husband passed. It’s also why I decided to do my dissertation on the theology and psychology of social status. I’m consistently blown away with how obsessed I am with achieving stuff despite the overwhelming evidence that achievements do not make me happy.

In the past decade of following Jesus, I received a pile of prophetic words that I was going to be a writer — many even predating my attempts at writing. So I started writing.

Since Christian writers usually pop up in Christianity Today, I figured that’s what I should try to do. I submitted around 212 essays to CT over the course of 3-4 years. I’m describing it casually, but it became a legitimate obsession.

When I finally got one accepted last summer, I was ecstatic, for about 7 minutes.

After that I moved my writing over to Substack and the process repeated, but this time, with more stats. Once I get 100 subscribers I’ll be content. Then 500, 1,000, 2,000, and so on. Even though I’m enormously grateful for these milestones, they weren’t as fulfilling as I’d imagined.

However, the one exception is the red check mark by the profile. If I get that, I will reach an eternal plateau of satisfaction.

The most embarrassing case of striving happened after I posted this article about John Mark Comer. Despite how much fun I had making the article, after I hit post, I found myself intoxicated by the likes or shares or positive comments. And the grossest part was: I didn’t just want the post to do well, I wanted it to do better than the anti-John Mark Comer posts I was writing in reaction to. But when it did, I didn’t feel happy for even a second – just gross that I cared that much. And so I had to repent.

It’s all a bit ridiculous, really. But these performance aspects are why social media is addictive. The number metrics lurking in every nook and cranny provide a preposterously easy way to know where you fit on its constantly rearranging hierarchy.

But even when your numbers are momentarily higher than another’s, it’s hard to find satisfaction in them. Numbers have an annoying way of reminding us of potentially higher numbers (i.e., Am I not a good enough writer to have 3,000 subs? Why does that person get more likes than me?).

After awhile, I just ask myself: what am I doing?

I cognitively believe that achieving superiority isn’t fulfilling, but it’s like I can’t shake the even deeper belief that satisfaction might arrive if I just get a little more.

Qoheleth, the mysterious author behind Ecclesiastes, was eerily aware of this feeling. He even described these dynamics of social striving: “All toil and all skill in work come from one person’s envy of another” (4:4).

And yet, he was also aware of how little this striving mattered in the long-run: “The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, nor bread to the wise, nor riches to the intelligent, nor favor to the skillful, but time and chance happen to them all” (9:11). In one way or another, time devours us all; it reveals where we’ve wasted our energy on temporal projects that pass away like so much sand on a cove stretching further than our eyesight.

But Qoheleth takes it even further. It’s not “only that those with superior skill and power sometimes lose but also that even when they win, their victories are pyrrhic. For all their industry, they ultimately end up empty-handed. Skill and toil in work born of striving for superiority are “vanity and a chasing after wind,” no matter how impressive their results may turn out to be (4:4).”14

Regardless of how we phrase it, the message is similar: if the goal is rising above others, striving is futile. Status doesn’t keep us warm at night. If all our eggs are in the basket of hallowing our own name rather than God’s, we’ve placed them exactly where discontent is guaranteed.

4. Pursue Excellence, Not Relative Success

So what’s the solution to all this striving? Volf suggests:

Rather than striving toward coming out on top, we should strive toward excellence for its own sake.

Yet, how to strive for pure excellence is, unfortunately, not the strong suit of Volf’s book. Like many Christian resources, it does far better setting up the problem than actualizing its solution.

However, I do think he’s right. Achievement anxieties really would get toned down if we pursued excellence rather than relative excellence.

In my personal experience, one thing that’s helped mitigate striving for superiority (or status games) is coming into a deeper awareness of our kinship as Christians.

Which, I realize, sounds odd; bear with me.

When new believers commit to following Jesus, the NT is explicit that this process inaugurates them into the family or household of God (Matt. 12:46-50; Eph. 2:19-22; Heb. 2:11-12). Yet, since family isn’t taken all that seriously in modern Western society, we miss how crucial this was.

In modern Western culture, it’s sadly common for kids to cut off their families over trivial political differences. But in the world behind the Bible, extricating yourself from kin was horribly immoral.15 It would tarnish your family’s sense of honor – the 1st century equivalent of status. And in a collectivist culture, the honor of your family is also your honor.16 So turning your back on your family would effectively cause a net loss of honor for both you and your family (partly why the prodigal son’s sin was so atrocious).

Now, this collective sense of honor comes with a weird clause that’s lost on us individualistic readers: if you compete with someone in your own family, you would, by default, cause a net loss of honor for you and your family.17

In Jewish and Greco-Roman cultures, competing for honor with rivals was normal, even encouraged; but competing for superiority with someone in your own family was deeply shameful. All that brotherly striving for superiority throughout Genesis was not the ideal. 1st century believers would’ve read those stories with a sense of disgust.18

You can probably guess where this is going. The New Covenant’s invitation to welcome all—regardless of ethnicity, class, gender, ideology, moral history—into God’s household brought each and every convert into this shared familial honor. In other words, entrance into this new family rendered competition amongst one another disgraceful.

As NT scholar Joseph Hellerman notes, “By positioning the Christian community as a surrogate family,” it subverted honor obsession among members by discouraging “adversarial competition in the church, for they were now brothers and sisters in the family of God.”19

This is one of the subtle implications behind Paul’s point that Christian community functions as one body with many members (1 Cor. 12:12-27). All the fighting amongst God’s kin in Corinth (1 Cor. 1:10-17, 3:1-23) was deflating the Gospel’s realization, so Paul urges they embrace a mindset that sees every member as inextricably unified. But rather than arguing for an equality of roles or callings, it’s more so aimed toward, as Volf argues, establishing an equality of honor.20

Paul continues, “If one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together” (1 Cor. 12:26). Beautifully, it doesn’t say we should suffer/rejoice together; it reads as if this suffering/rejoicing will naturally happen — almost like how a body can’t help but feel what another part of the body is going through.

However, the verse reveals a sad yet obvious expectation meets reality issue: us moderns are much better at the suffering together than the rejoicing together. We tend to surround those who are grieving but disperse when they’re thriving. Which is sad, because it fosters a culture that ignores celebration.

That said, when I catch myself getting jealous of a brother or sister in Christ, I try to remind myself of kinship. If we really are a family (which, according to a biblical worldview, we are), then my envy doesn’t just harm me; it harms the whole body.

I’ve also been trying this thing called “sympathetic joy.”21 Think about how you console someone in response to their failures or losses. Sympathetic joy is basically that, but instead of mourning in light of loss, we celebrate in light of success.

It’s a way of trying to see others’ victories as a victory for everyone in the household. Do they have a book coming out? Rejoice. Are they receiving accolades? Rejoice. Did they get a great job? Rejoice.

In terms of writing, this inspires me to relearn how to write for the sake of writing; to do it because it’s something I love to do, because I like it, because I’m halfway good at it and it’s what I’m called to. The more I approach it as an avenue for competition, the less I enjoy it, the less resonance my soul feels with it, and the more my insecurities tarnish its potential for God-honoring excellence.

All to say, striving for superiority is a tad silly, because it doesn’t exist. It’s a momentary illusion, a short-lived rush that’s quickly replaced with low-grade anxieties about what happens when we don’t win. We should aspire to do great things and cross milestones — but striving to elevate ourselves by lowering others will never make us happy.

The only kind of striving Volf does affirm is the kind that strives to leave others feeling more honored, more important, than ourselves (Rom. 12:10). Which is a great litmus test we can apply to any project: am I doing this primarily to refine my own ego or to actually offer something substantial to the world? And if we find, as we all will every now and then, it’s more so about the first reason, then just edit, edit, edit, until it starts feeling closer to the second.

Not every part of Brooks’ book and research was 100% spot on (Henry Oliver wrote a great book pointing out some of the flaws in Brooks’ thesis), but this point seems pretty spot on Arthur C. Brooks, From Strength to Strength (New York: Penguin, 2022), xiv.

If you’re curious about the Bertrand Russell quote: Bertrand Russell, Power: A New Social Analysis (London, UK: Allen & Unwin, 1938), 149. On why status is more an issue in a post-meritocratic society as opposed to a pre-meritocratic society, see Griffin Gooch, “Deinstitutionalising Meritocratic Plausibility Structures Through the Redignification of Ordinary Life,” International Journal of Public Theology (Forthcoming, 2025). Or you could just google it.

If you have a child in a high performing educational environment, I strongly suggest you check out Jennifer Breheny Wallace, Never Enough (New York: Sentinel, 2023).

Miroslav Volf, The Cost of Ambition: How Striving to Be Better Than Others Makes Us Worse (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2025), 6.

Volf, The Cost of Ambition, 18.

Volf, The Cost of Ambition, 163.

Dorothy M. Scura, ed., Conversations with Tom Wolfe, 44.

Edmund Leach, Culture and Communication: The Logic by Which Symbols Are Connected, 54.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality among Men or Second Discourse,” in Rousseau: The Discourses and Other Early Political Writings, ed. and trans, Victor Gourevitch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 111-231 (at 224).

Blaise Pascal, Pensées, trans. Roger Ariew (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2005), Fragment 978.

Rousseau, Second Discourse, 189.

This point is covered throughout Brooks’ From Strength to Strength.

Volf, The Cost of Ambition, 8.

Volf, The Cost of Ambition, 8.

It’s still extremely unthinkable in many Eastern and collectivist cultures to this day. See E. Randolph Richards & Richard James, Misreading Scripture with Individualist Eyes: Patronage, Honor, and Shame in the Biblical World (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2020).

David deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity: Unlocking New Testament Culture (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2nd edn., 2021), 168.

See Joseph H. Hellerman, The Ancient Church as Family (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001), Ch. 3-4.

deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship, and Purity, 186.

Joseph H. Hellerman, Embracing Shared Ministry (New York: Kegel, 2013), 191.

Volf, The Cost of Ambition, 114.

The title “sympathetic joy” comes from Johann Hari’s Lost Connections. I realize the phrase is sometimes used in the Buddhist tradition, but it has a stronger origin in the Christian tradition: “Weep with those who weep and rejoice with those who rejoice” (Rom. 12:15).

I strive to have the top comment on this post and nothing will get in my way.

“Sympathetic joy!”

Absolutely love this concept.

If our hearts are postured to rejoice with others, I think it will increase our ability to be positively motivated to add our own contributions to the Body of Christ, instead of wanting to one-up someone in the same pursuit. Posturing our hearts in celebration helps to spur one another on in good works.

Great article, Griffin!!!