Why ChatGPT Might Not Be Sinful But It Is Definitely Sad and Kind of Lame

Framing Generative AI in Terms of Spiritual Formation

Audio voiceover available here for paid subscribers!

The Nerd’s White-Collar Crime

I love footnotes.1

The times in my life I’ve most sold out my personality are the times I’ve joined the chorus of classmates groaning about finalizing footnotes for their final papers. I’ve never groaned about footnotes behind closed doors. Citations are one of my love languages.2

The thrill some people get from organizing their kitchen or polishing their car or touching up their canvas is how I feel about footnotes. It’s a form of ordering the disordered (i.e., the endless web of disconnected knowledge) into some loose rhythm, kind of like punching a new pushpin on a string board that reframes the whole investigation.

But a while back I had a semester where I took on way too many credits. I was averaging 4 hours of sleep while knee-deep in memorizing Greek vocab and Mounce’s square of stops.

I mentioned to a friend that I was struggling to keep up with my capstone paper, and he told me ChatGPT could save me some time by churning out perfect citations.

I reluctantly tried it out. They weren’t perfect. Almost every one of them had some kind of mistake. Typically, little stuff – like a misplaced parenthesis or the city the publisher was located. Other times, much bigger stuff – like the book title or the page number.

One day I was tweaking a paper on my phone during a break at work and remembered a study I’d come across that morning. But I didn’t have time to pull out my laptop, so I asked ChatGPT if they could locate it. I copy and pasted the one that matched my description and threw it in the Word doc. But after going back to work, I forgot to double check the source.

It was fake.

This is how I learned that generative AI “hallucinates” sources to give the user what they ask for. Thankfully, we caught it during the phase of the project where students were peer-reviewing one another’s papers. But it was still enormously embarrassing. Not so much because I disappointed another student, but because I tiptoed around my own values for the sake of convenience.

—

GenAI is such a hot topic these days. And since there are already thousands of articles and podcasts about it, I’m not gonna pretend to write anything “new” here.

Instead, I’m just hoping to provide a Reality Theology explanation for why we should discourage using GenAI in any realm of our lives that’s even marginally important.

Lots of Christians talk about using AI in terms of whether it’s sin or not sin. And even though I definitely lean way more toward the luddite end of the spectrum than the end that encourages using it, I don’t like framing it in such black-or-white terms.

Which is why I really liked this piece from O. Alan Noble. Bonnie sums it up well in this note:

It inspired me to think less about GenAI in terms sin and start thinking of it in terms of formation. In other words,

what kind of person does using ChatGPT turn us into?

Let’s start with the basics:

ChatGPT makes us rely on subpar information.

After the fiasco with that hallucinated footnote, I started testing ChatGPT to gauge its accuracy. Turns out, it wasn’t just hallucinating sources, it was fabricating quotes, messing up summaries, and paraphrasing data until the gist of the original sources were unrecognizable.

For example, if you ask it, “Can you generate some quotes from C.S. Lewis?” you’ll get a few legitimate C.S. Lewis quotes mixed with some quotes Lewis never said.

Someone suggested this was because I didn’t ask ChatGPT to double check to verify its findings. But this barely helped. Sometimes it took as many as five promptings to get an appropriate answer.

And for the record, if you have to consult something five times to get an accurate response, that’s a good a sign as any that it’s a subpar tool. Imagine if it took you five promptings to get a professor to spill a decent answer. Obviously, you’d stop consulting with that professor, especially given that all the false info you’d gather along the way guarantees an incredible amount of confusion.

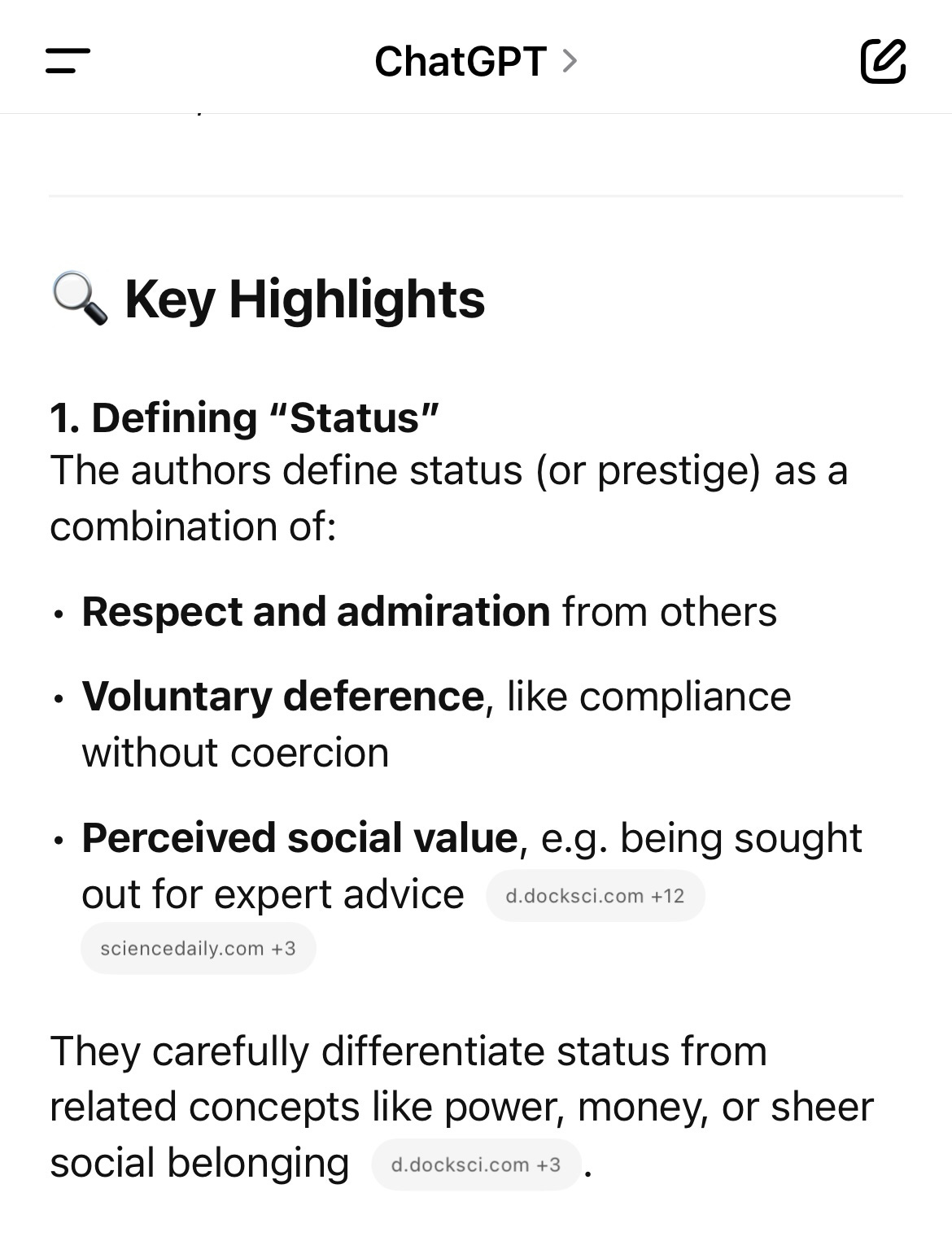

Next, I asked ChatGPT to summarize one of the studies I interact with in my dissertation:

It was already wrong in the first bullet point. The third quality isn’t listed correctly (it’s “perceived instrumental social value”). And it isn’t “being sought out for expert advice,” it’s “the degree to which other people perceive that an individual possesses resources or personal characteristics that are important for the attainment of collective goals.” Sure, you could argue that the two definitions are related — but they’re not related enough that the ChatGPT summary could allow a student to pass an exam question about it.

Then I tested it out with a general research question (“Are there any Christians throughout history who said that prayer changes the petitioner and doesn’t influence God?”), and one of the first names it spit out was Augustine. But Augustine never said anything like that. It took some of his more nuanced quotes about prayer and then construed them to fit my question.

It does this because it makes assumptions about the kinds of responses that’ll satisfy you. Then it does some syntactical gymnastics with the sources until it can shape a response that fits your agenda.

In other words, it simplifies and summarizes and paraphrases the truth until it’s a version of the truth that the user likes.

Which, if you’re just looking for info on the best episode of Lost, isn’t that big of a deal. But for crucial questions, such as anything pertaining to life, faith, and theology, this obviously becomes a bigger deal.

But many still find GenAI too efficient to stop using. Which is troubling, because early research about GenAI use shows that students and scholars who rely on

ChatGPT will learn approximately nothing.

GenAI only produces the “illusion of learning.”

This is because information embeds into your long-term memory through careful attention, deliberate focus, and reformulating that information in your own voice.3 ChatGPT bypasses all of those steps.

It undermines genuine learning by curating what the theologian A.J. Swoboda calls “self-selected content” — a streamlined form of research that blurs out everything other than the exact thing you were looking for.

Which is super convenient, but it bypasses what literary critic Alan Jacobs calls “serendipitous learning.” It’s the kind of learning that happens naturally while weeding through resources trying to find whatever you were originally looking for.4

While the search engine definitely did away with lots of serendipitous learning, ChatGPT obliterates it.

Serendipitous learning is crucial to the art of communication, written or otherwise. It helps you build a full picture instead of just curating what you’d prefer to notice. You become less likely to approach your topic like a prosecutor who refuses to acknowledge the defendant’s counterpoints.

Personally, I don’t typically start writing on a topic until I’ve read 4-5 books and 3-10 peer-reviewed articles about it. It’s why I’ve rarely ventured to write about Destiny’s Child. On average, I’ll probably read around 200,000 words per project. But I only really use around 2,000 of those words for the final draft.

From a strictly pragmatic perspective, that’s about 198,000 words-worth of wasted time and energy. But of course, none of the extra research is actually wasted.

The extra serendipitous learning teaches you what not to say, what isn’t important, how to avoid generalizations, and how to verify the accuracy of your information to an excruciating tee.

The way it never asks you to dig past elementary level summaries also goes to show why

ChatGPT is really not that impressive.

Save for some graphs and images it can generate, I’ve yet to see ChatGPT do anything more impressive than a Google search. It seems like the biggest difference is that a Googler has to amalgamate the search results themselves, while OpenAI does the summarizing for the user.

“But it saves so much time!”

Not really. A recent pre-release study argues that it actually costs 10x more energy to do research with GenAI than a Google search:

“But ChatGPT can give me a meal prep plan!”

Yes, and so can a cookbook.

“But it can make charts and graphs and art!”

Yes, inaccurate charts and graphs, and bad art. All of these things are more convenient, sure; but none of them seem strictly impressive.

“But if we don’t learn how to use OpenAI now, we’ll never catch up when it gets more powerful.”

I roll my eyes every time I hear this argument. It feels way too Big Tech propaganda.

GenAI is complex, but it’s not and never will be more complex than the human brain — mainly because, despite centuries of effort, we still know surprisingly little about how the brain works.5 ChatGPT is smarter than us in many ways (as was the abacus), but it has no consciousness.

It can’t make value judgements, which means it probably doesn’t desire world domination. The more realistic concern is how it’ll affect the job market in years to come.

But even more than taking jobs, it also deteriorates our ability to carry out whichever jobs it takes. The more we outsource vital functions to AI, the more

ChatGPT will degrade our basic skills.

In tech writer Nicholas Carr’s The Glass Cage, he warns about the way automated technology causes our skills to atrophy.

To explain, he points to the 153 people who died in plane crashes from 2002-2011.6

Which is, of course, tragic; but proportionally speaking, of the 7 billion flights and well over 350 trillion passengers in that timeframe, 153 is not the worst number – especially when compared to the 1,696 deaths out of 1.3 billion flights that took place from 1962-1971.

Interestingly, the reason these planes crashed wasn’t so much because of a tech malfunction as it was a pilot malfunction.

Since 1988, most commercial airlines began programming their planes with an autopilot system. Meaning that, since 1988, pilots have been flying manually less and less.7

And just like anything else in life that you stop doing frequently, when you pick it up again, you’ll find your skills a little shaky.

So anyways, what happens when the autopilot system breaks due to something like extreme cold temperatures or a chip malfunction?

These pilots, who had gone through all the necessary training, literally forgot how to fly. In moments of distress, they found their reliance on automated technology had atrophied their skills. Thus, 153 deaths.

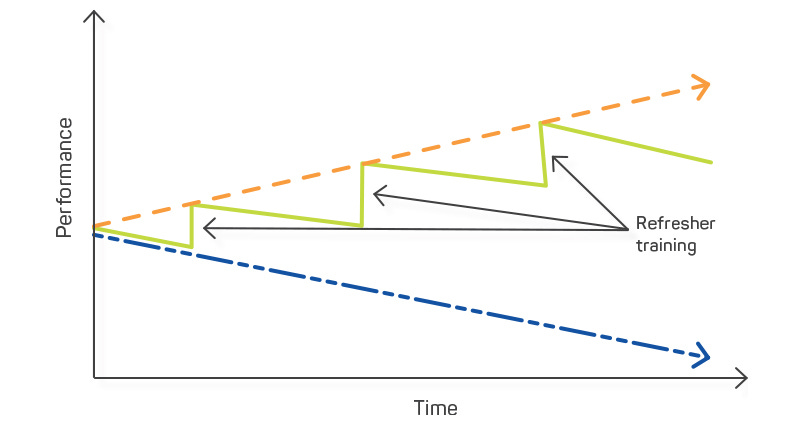

Of course, this is an extreme example. But the point is: relying on technology to do jobs for us causes what social scientists call “skill fade” — the sacrifice of whatever hard-earned muscles we gained.

So if we outsource our creative thinking, researching, or Scripture exegesis to ChatGPT, we’ll gradually lose the ability to do those things well without ChatGPT.

There’s even research to support ChatGPT’s skill fade. One recent study split students into groups and asked them to complete schoolwork. They initially found that the students with access to ChatGPT-4 outperformed other students. But when the AI was taken away from those students, their grades plummeted.8

Basically, if you’re a B student, using ChatGPT could turn you into an A student. But if you rely on it long enough and then have it taken away, you’ll drop to a D student.

This tradeoff shows why it’s helpful to frame

ChatGPT as a Faustian bargain.

In German folklore, Faust was a successful scholar who couldn’t shake a sense of dissatisfaction from blanketing his daily experience. And so he makes a deal with the demon Mephistopheles, surrendering his soul in exchange for magical power over reality.9

Predictably, in every version of the story, the tradeoff isn’t worth it in the long run.

It’s essentially a “deal with the devil” cautionary tale. You sacrifice something that you don’t think is all that important to gain power and/or instant gratification, but the thing you sacrifice ends up costing way more than whatever you gained.

GenAI is the epitome of a Faustian bargain. It promises convenient research at the expense of quality info and our ability to think critically.

Thinking critically and clearly might not top the list of priorities for everyone. But I’d wager that the costs of losing them are not worth the convenience ChatGPT offers. This brings us to the way

ChatGPT undermines God’s cultural mandate.

After creating humans, God ingrained His image in us and gave us what’s called the “cultural mandate” (Gen 1:26-28).10

This mandate implies a lot, but essentially, it’s the responsibility to order the things of earth in a true and good and beautiful way.11 It isn’t just about assigning animals nice names; it’s about righteously rearranging all realms of life, including the whole web of human knowledge.

Interestingly, the ability to sort through information coherently is actually one of the main features (that’s scientifically provable) that sets humans apart from animals. Our enormous frontal lobe gives us an inner theater for the imagination to comprehend knowledge acquired in the past and plan for the future accordingly.12

So the proper ordering of false information into true (or true-er) knowledge has been one of humankind’s central tasks from day one. In fact, over and above typical intelligence tests like IQ exams or SAT’s, many social scientists believe that one of the truest marks of human intelligence is the ability to make connections between seemingly disparate chunks of information.13

So is it really worth using GenAI if it outsources and then atrophies one of the unique skills God placed in humans?

On a similar note,

ChatGPT undermines critical spiritual formation processes.

Recently, a new GenAI marketed toward ministry workers called “Gloo” popped up. Its tagline: “AI you can trust for life’s biggest questions.”

Which I found enormously depressing. We can barely rely on AI for basic questions — such as things C.S. Lewis said, the content of an academic paper, or the basic views of the world’s most discussed theologian — let alone life’s biggest questions.

Another one of Gloo’s taglines: “Spend less time on tasks, more time on ministry.” Its subtitle says that if you allow your employees to use Gloo, they’ll have more free time to grow your church.

This is also depressing — and untrue. Technology is supposed to save time, but there’s little research to suggest that we put whatever time we save to good use. In fact, research we do have suggests we use whatever time we save in a uniquely wasteful way.14

If you’re already prone to laziness, procrastination, or scrolling, a tool that allows for more free time will simply give you more time for laziness, procrastination, and scrolling.

One of the biggest things I come back to is the question of why research is such a tempting activity to outsource. It’s just as much a part of our spiritual formation as any other discipline. The early church saw intellectual formation as a crucial spiritual practice, since it formed one’s thoughts toward beholding God in every realm of life.15 We wouldn’t outsource prayer or fasting – so why is outsourcing research any more attractive?

Same thing goes for writing. As Flannery O’Connor put it, “I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.”16 Writing our thoughts helps us reflect on them until we learn more about ourselves – along with logic and structure and reasoning and all that.

It’s also rarely as much of a drag as we assume; as James K.A. Smith put it, when we outsource the writing process to AI, we miss out on a “distinct source of joy.” As philosophers and followers of Jesus have noticed throughout millennia, disciplining yourself often leads to a joy that makes the struggle worth it. College students might complain about cramming, but in the long run, the effort they invested usually leaves them happier than if they’d just phoned it in.

God’s gifted each of us with a unique capacity to reason, think, create, and rule. And even if you don’t feel like God’s gifted you in a research capacity, I guarantee He’s gifted someone around you.

Which brings us to the last point:

ChatGPT undermines the common good.

In 1 Corinthians, Paul described different roles and giftings that make up a flourishing church body (1 Cor. 12-14). Each person’s unique gift contributes to the “common good.” And two of those gifts, often collapsed into the same idea,17 are wisdom and knowledge (1 Cor. 12:8).

In one sense, this highlights the importance of having someone who can deal out practical life advice. But in another sense, it’s also about having someone who knows the Scriptures really well.

In other words, a Bible nerd is a wonderful appendage to any church’s body. They’re a beacon of guidance for their church, and fulfilling their role simultaneously helps them feel needed. It’s a mutual win-win for church’s common good.

So if we think about it from this angle, GenAI threatens to subsume the role of the Bible nerd in the local church (while simultaneously doing their job egregiously poorly). Further, since so many in the younger generation now seek emotional advice from ChatGPT, it can also subsume the role of the counselor, the spiritual director, or the mentor. And as in pilots relying on autopilot, the more ChatGPT fulfills these roles, the more we lose the art of conversation.

Ok it’s probably high time to

be done now.

The other day I was trying to reference a source that was entirely German. Having not learned German, I do not know German.

I threw the citation into Google, but all results were unsurprisingly German. I sighed, pulled up ChatGPT, and asked it to turn the German citation into English. As far as I can tell, no harm done (I suppose you could accuse me of putting German scholars out of work, but I can’t be perfect).

I don’t think total AI abstinence is necessary; we should just understand the way it forms us. Like any other tool, if we become over reliant upon it, we’ll lose our ability to function without it. But I also wouldn’t try to put a Phillips head screw into a wall with my bare hands if there’s a Phillips head screwdriver laying around.

So rather than saying “just don’t use AI,” we should instead explain the formational, emotional, and ethical consequences of consulting GenAI for life’s important questions. And even for non-important questions, we should still stave off using it until as late as possible, after we’ve given a healthy, human touch to whatever we’re working on.

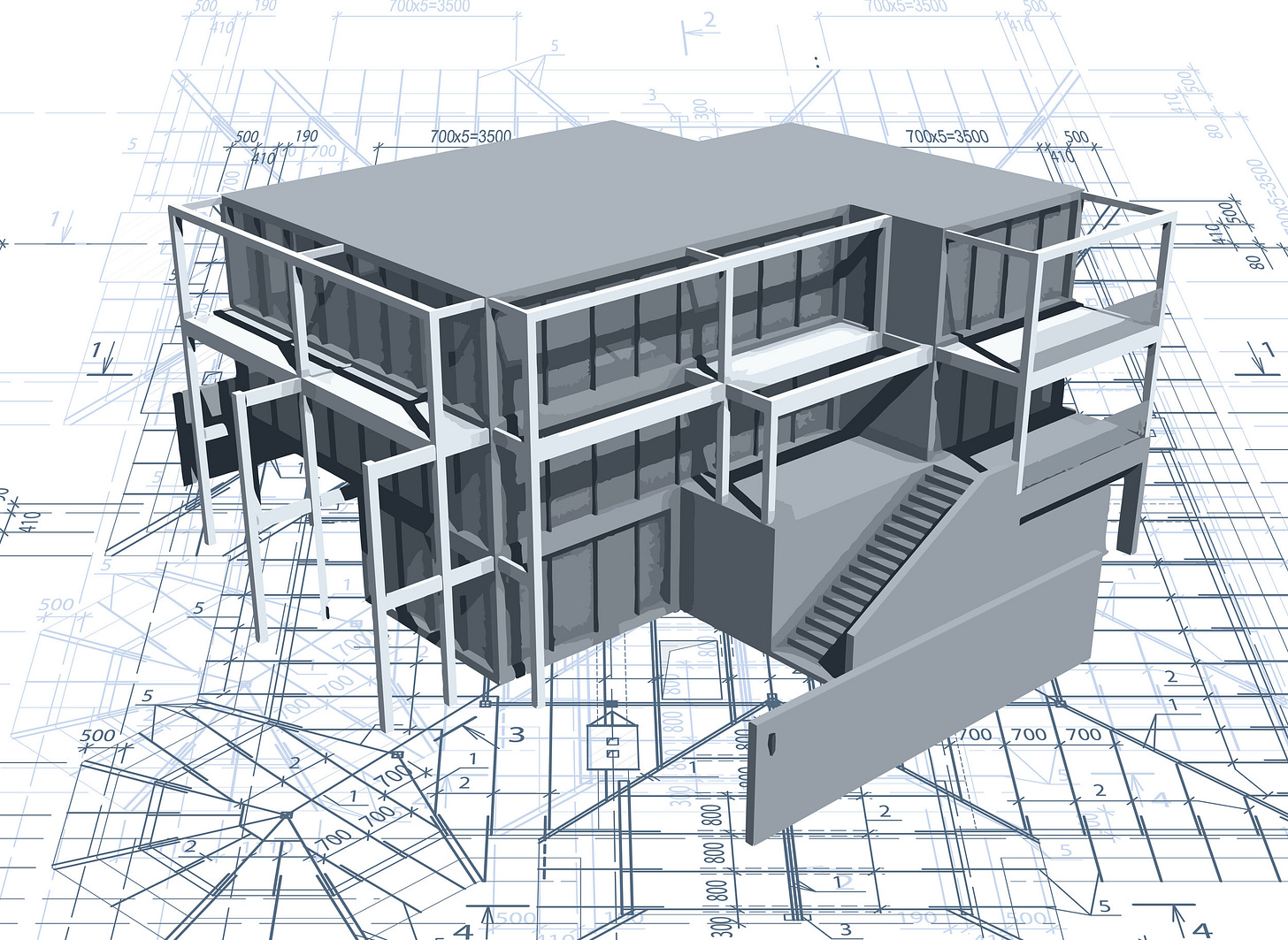

For example, after architects adopted the CAD automated design program, several scholars noticed that it was deteriorating manual design skills. But rather than throw the baby out with the bathwater, they simply started delaying the involvement of the technology until later in their projects. This allowed them to use their imaginations to provide the necessary human touch to the designs. Then once they were far enough along, they pulled in the AI just to finish dotting the I’s and crossing the T’s.18

As long as someone has actually allowed themselves the time and effort and practice to refine their skills in a way that honors their mind and body and calling, GenAI’s potential downsides go down a bit.

But even still, there are certain realms of life that I personally consider too sacred to let AI touch. I’ll never ask it for therapeutic advice, relational tips, potential theses, sermon prompts, etc. I’ll never ask it to touch one of my articles. And maybe that makes me a paranoid luddite. And I’m fine with that. I’d rather engage my own creativity in the projects that matter to me even if I end up churning out an inferior product than whatever ChatGPT could produce.

From a purely formational perspective, it doesn’t seem to form us into anything more virtuous than we were before using it. From the times I’ve used it, I’ve only felt more hurried, impatient, and efficiency-dependent.

I’ll end with a personal paraphrase of something Wendell Berry said about computers:

When somebody has used ChatGPT to write work that is demonstrably better than Dante's, and when this better is demonstrably attributable to the use of ChatGPT, then I will speak of ChatGPT with a more respectful tone, though I still won’t recommend it.19

Recommended Reading

This other article from

This from

andThis from

This from

This from

This from

This from

This from

ALSO this great article by

that just came out today!The Glass Cage and The Shallows by

This pre-publication paper about the effects of OpenAI usage by MIT researchers.

Not Recommended Reading/Listening

Anything by the guy who argued in favor of AI use in ministry in this podcast. His arguments were so frustrating that I started writing this article.

Sadly, I couldn’t fit as many footnotes in this piece as I’d hoped! I barely cracked 20. See this post to get a feel of how obnoxious I can be with footnotes.

I’ve gotten to the point where I flip to the endnotes before starting a book and then start the returns process if I don’t like what I see. The lack of bibliography probably isn’t because the author had an aggressively original idea; it’s more likely they just hadn’t researched enough to realize how unoriginal their idea was; there is nothing new under the sun.

See The Shallows, The Glass Cage, Peak, and Hidden Talent.

Buchem, Ilona. (2013). Serendipitous learning: Recognizing and fostering the potential of microblogging. 11.

Per E. Roland, “How Far Neuroscience is from Understanding Brains,” Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience vol. 17 (2023): 1147896.

Nicholas Carr, The Glass Cage: How Our Computers Are Changing Us (New York: Norton, 2014), 43-63.

I consulted with my friend who’s a pilot. He said lots of pilots rely on autopilot, but not to the extent that Carr insinuates. Just like any other job or field, there are many pilots who are devoted and maintain high standards, and many who are lazy. But the lazy one’s who don’t do much manual flying are very rare, apparently.

Hamsa Batstani, et al., “Generative AI Can Harm Learning,” The Wharton School Research Paper (2024): 1-59.

Andy Crouch mentions this frequently in his podcasts and writings, but I think he may have been inspired by Wendell Berry’s essay “Faustian economics.”

N. Gray Sutanto, “Cultural Mandate and the Image of God: Human Vocation under Creation, Fall, and Redemption,” Themelios 48 no. 3 (2023): 592–604.

Paul S. Jeon, “The Cultural Mandate according to Paul’s Letter to Titus: Brief Exegetical-Theological Meditations.” The Expository Times 136, no. 5 (2025): 185–95.

Some people think squirrels do this because they gather nuts and bury them during winter prep. But in reality, they’re simply following their genetic code by reacting to changes in the position of the sky and weather conditions. See Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness (New York: HarperOne, 2008) Ch. 1.

See also Ling-ling Wu and Lawrence W. Barsalou, “Perceptual Simulation in Conceptual Combination: Evidence from Property Generation,” Acta Psychologica 132 no. 2 (2009): 173–189; Mathias Benedek, et al. “Intelligence, Creativity, and Cognitive Control: The Common and Differential Involvement of Executive Functions in Intelligence and Creativity,” Intelligence vol. 46 (2014): 73-83.

Ruth Ogden, Joanna Witowska, & Vanda Černohorská, “Technology is Secretly Stealing Your Time,” Scientific American, December 19 2023, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/technology-is-secretly-stealing-your-time-heres-how-to-get-it-back/.

Ross Inman argues this wonderfully in Christian Philosophy as a Way of Life (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022).

Flannery O’Connor, The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor, ed. Sally Fitzgerald (New York: Vintage Books, 1980), 5.

Kimlyn J. Bender, R. Reno, Robert Jenson, Robert Wilken, Ephraim Radner, Michael Root, and George Sumner, 1 Corinthians (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2022), 285.

Carr, The Glass Cage, 137-147, 169-170.

Wendell Berry, “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer,” in What Are People For? (New York: North Point Press, 2000), 172.

I couldn't agree more, Griffin. When I hear about someone using AI for academic or creative pursuits, I think about that children's book "The Magic Thread" where the little boy pulls the thread any time he wants to jump ahead in life and get to the exciting parts. He essentially misses his entire life and then gets to the end and wishes he had never pulled the stupid thread since he was barely living his one, irreversible existence. If it could clean my toilets for me I guess I would be tempted, but reading the books and analyzing the summaries and creating the art is the whole point of living. Why would we try to shortcut existence? I think you are right that it is sad more than sinful, but I have such a kneejerk antipathy to it as a writing teacher. That stupefying, numbing, minimizing effect on a human brain is what feels so malevolent. Really good thoughts!

Brilliant Griffin.

One thought that came to mind whilst reading this is ChatGPT/AI may (and I stress only 'may') help us to do more stuff, but will it help us become more human, more who we have made to be as thinking, creative, relational beings, or will ChatGPT displace these human attributes in us and erode our capacities to pick them up again once the machine is taken away? I think the answer is clear from what you have written.

Sacrificing what makes us human is not something I am willing to do, even if I am able to do more/be more productive. Humanity trumps productivity any day. It is a pity our politicians don't think so.