Why Hard Work Doesn't Always Pay Off

The Failures of Meritocracy and Finding Satisfaction in the Ordinary

The following is a condensed version of an academic paper that was just published by the International Journal of Public Theology. If you’re interested in reading that, just DM me your email and I’ll happily send you a pdf copy.

Audio voiceover available here for paid subscribers!

#Blessed

The theologian Dallas Willard said that there are four questions of the utmost importance that we all need to ask ourselves:

That second one always sticks out to me. It’s the kind of background question that subtly informs our waking decisions: what makes someone actually well-off, blessed, or happy?

Depends on your worldview, but most Westerners would consider a #blessed life to include: wealth, success, popularity, possessions, romantic fulfillment, power, and so on.

But what if we asked about how someone becomes well-off?

That’s even easier to answer. 95% of Americans and 90% of UK residents agree: hard work.1

It’s the kind of deep-seated belief that the sociologist Peter Berger calls a “plausibility structure.”

Which is way simpler than it sounds; plausibility structures are the “sum total of our knowledge of the real world and the explanations for why things are the way they are.”2 They’re like a brain filter that we sift all new data through.

For example, the Resurrection is a Christian plausibility structure. Like Paul wrote, if there wasn’t a Resurrection, our faith is futile. But since the Resurrection happened, we should now adjust our understandings of reality around and in and through it (1 Cor. 15:12-34).

Now, there are very (very) few plausibility structures 90% of Westerners agree on, but this is one of them: a successful life is the result of hard work, effort, and talent.

This belief is one of the foundations of meritocracy (a socio-economic system that rewards people in proportion to their effort and talent).

Meritocracy promises this equation:

But sadly, this model isn’t as fool proof as we might think.

There’s increasing evidence that meritocracy isn’t working as it should – and maybe never even worked in the first place.

To explain, let’s talk about the move from

Aristocracy to Meritocracy.

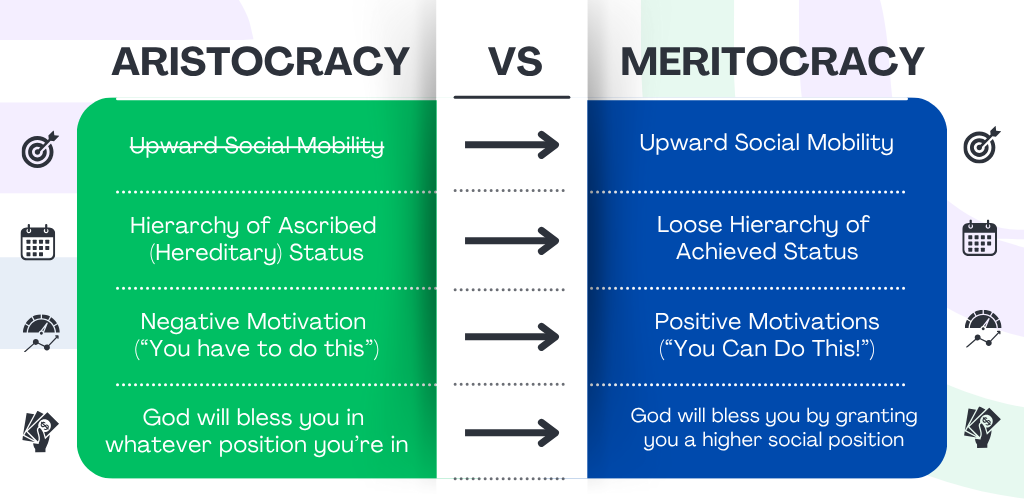

Upward social mobility is a new-ish phenomenon. For the majority of human history people “were locked into a given place, a role and station that was properly theirs and from which it was almost unthinkable to deviate.”3

In aristocracy, the status quo looked like: you were born within a hierarchy of ascribed status that decided your social rank based around ethnicity, lineage, generational occupation, and gender.4 There was little hope of ascending to a higher echelon.

But even though some disliked their social class (being a peasant isn’t much fun in any era), people didn’t experience the same kind of frustration about it as they do today. This is because most societies were religious, which brought an understanding that social position was set in place by God.

So when societies shifted from aristocracy to meritocracy, the invention of upward social mobility also invented resentment toward social position. No matter where you were on the hierarchy, there was always potential to get higher. And your position was no longer society or God’s fault; it was entirely in your own hands.

This shift transitioned motivations away from the negative (as in, “It is a legal requirement for you to do this”) and toward the positive (as in, “You can do this!” “No days off!” “Don’t let them see you fail!”).

Even though these Peloton-ish mantras might seem inspiring, they’re exhausting. They wage war against our mind and body’s impulses that tell us to stop, slow down, rest, or accept our failures and limitations.

All to say: in aristocracy, if you’re unsuccessful, it’s not your fault — and God can still bless you in the position He’s placed you in.

But in meritocracy, if you’re unsuccessful, it’s all your fault — and, if God really is good, He’ll want to bless you by moving you up and to the right. Struggle, suffering, or falling behind become signs that you’re not working hard enough.

Great. Now let’s talk about

Why Meritocracy Doesn’t Work.

While many opinion writers and podcasters overcomplicate this issue, it’s not really controversial among the scientists who study it. Essentially, modern meritocracy fails because the people who get ahead are statistically more likely to start out already ahead; those who get behind are typically those who started out behind.5

Kids from wealthy families with below average test scores still have a 7 out of 10 chance of reaching the top percentile of wealth and education, while kids with above average test scores from low-income families only have a 3 out of 10 chance.

80% of kids from high-income families will attend college, compared to only 36% from low-income families.

Over 66% of Ivy League students come from the highest 20% of the income scale.6

Schools like Princeton and Yale educate more students from the top 1 percent (a yearly household income of over $630,000) than from the bottom 60 percent combined.7

The same goes for Harvard and Stanford; even in spite of remarkable financial aid funds and endowments, less than four percent of Ivy League students come from the bottom fifth of the American income scale.

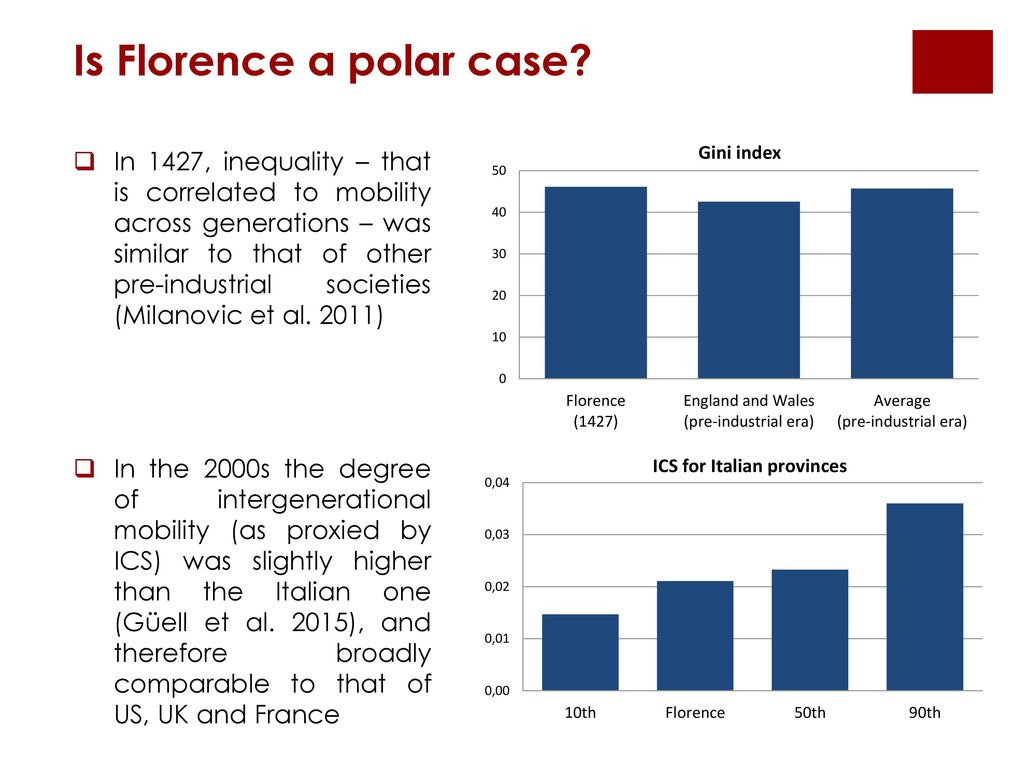

In one of the wilder studies about this phenomenon, researchers gathered tax information from 1427 Florence (25 years before da Vinci, which is crazy) and traced their lineage across 600 years to modern tax records. They found that over a half-millennium later, the descendants of rich Florentines still owned over 12% more wealth than the ancestors of poor Florentines.8

And this trend doesn’t just track within Italy; similar findings have popped up in Sweden and England.

What’s even more surprising is that geneticists have found that we share less than 1% of our DNA with our ancestors after seven generations. And yet this study shows that wealth passes on at a higher percentage even after twenty generations.9 In other words, we inherit more of our ancestors’ social status than DNA.

Unfortunately, more examples:

High schoolers’ SAT scores rise more so in proportion to income than intelligence.10

Despite promises made by Ivy League schools about the opened doors and bright futures they’ll provide, their graduates’ future income is still more likely to resemble their immediate family’s than other graduates’.

Elite universities aren’t helping ease the gap either. In a study of 50 competitive colleges from 2006 to 2018, admissions rates dropped an average of 45 percent – going from accepting around 33% of applicants to accepting less than 25%.11

To top it off, sociologist Sean Reardon demonstrated that he could predict the education level and average income of unborn children with haunting accuracy simply by knowing their zip code.12

Even though we hope that a blend of hard work and talent create success, the consensus is that two other factors deserve the most credit: (1) the socio-economic status we inherited through birth and (2) luck.13

If We Believe Hard Work Pays Off, and It Doesn’t, Then That’s Bad

Now this is where plausibility structures come back in: if we really believe effort is all it takes to get ahead, people will attribute their success to their own talent or hard work rather than advantageous circumstances or luck.

But this creates a worldview that’s governed by karma. I got what I got because I earned it; you got what you got because you screwed up.

As the philosopher Michael Sandel notes, modern meritocracy revives the “antiquated ‘Biblical’ ethic that those who flourished must have earned God’s favor and that suffering is a sign that someone sinned.”14

The fallout from this belief isn’t just embarrassment. Failing to measure up to arbitrary benchmarks of success is a significant driver of a unique kind of depression — what philosopher Alain Ehrenberg calls the “malady of inadequacy.”15

The social theorists Anne Case and Angus Deaton even made a connection between falling short of society’s standards and what they call “deaths of despair” (deaths from suicide or overdose), which are presently the leading cause of death in the States.16 Apparently for males, who make up 75% of all deaths of despair, the biggest determining factor in whether they’ll experience a death of despair is whether they have a bachelor’s degree.

This isn’t just happening in “secular” society — it’s also hitting the church. Apparently, the bottom fourth of the American income scale is “dechurching”17 faster and in larger numbers than any other demographic. Other research from Ryan Burge shows that demographics with the most education are most likely to stay in church, while those with the least education are the least likely to continue attending.18

Whereas the early church was famously a space where people of different backgrounds, classes, and status, could set aside those differences for the sake of worshipping together, the modern Western church is apparently collecting more and more people of a higher income and pedigree.

People have noticed this issue for awhile — it’s just never been a popular issue. You’re much more likely to hear churches discuss the need to gather diverse ethnicities than diverse incomes.

Pope John Paul II noticed these tensions over 40 years ago. He said that fixing the dissatisfaction among those who fall short of society’s standards was the “key to the whole social question.” His point was that if we didn’t figure out how to offer equal dignity and respect to all workers — of all fields, industries, income, education-levels, and so on — then we’d never build a society that could actually flourish.

Other experts in the field agree: the solution isn’t throwing money or degrees at people; and it’s also not encouraging people to wallow in anger at the system. Rather, it’s figuring out how to afford all people a sense of dignity regardless of whether they meet an Americanized vision of a #blessed life.

Thankfully, Martin Luther already drafted a solution back in his day. It’s called

“The Affirmation of Ordinary Life.”

After contributing to the Reformation, Luther changed directions from talking about “works” to talking about “work.”19

Specifically, he wanted to look at how work and labor related to calling. In Luther’s time, the only vocations that were called “callings” were clergy-related.20 Ministry vocations – what we today might call jobs in the Christian subculture – were seen as godlier than “secular” vocations like farming or smith-ing.

But Luther rejected the idea that church work was inherently better than “secular” work. “Every occupation has its own honor before God, as well as its own requirements and duties.”21

Doing laundry, cooking, cleaning, sleeping, raising children, eating, and chores aren’t just the good life’s background noise. Christians could access the good life in the here and now through worshipping God within and through the ordinary tasks of daily life.22

It’s beautiful that Luther was the one making these arguments. He changed human history more than almost any other theologian. But in spite of all the honor that he could’ve hoarded, he was one of the most vocal supporters of redistributing it. Not in the sense of assigning everyone the same roles, but assigning everyone equal honor.

This wasn’t just lofty over-spiritualizing; Luther realized all jobs were actually necessary for a flourishing society. The medical practice stops functioning if you lose a doctor, sure. But it also stops functioning if you lose the receptionist. One job requires more schooling, but both are needed for the workplace to function and prosper.

MLK Jr. even championed spirit of the earlier Luther in his sermons:

One day our society will come to respect the sanitation workers if it is to survive, for the person who picks up our garbage is in the final analysis as significant as the physician, for if he doesn't do his job, diseases are rampant. All labor has dignity.

We need Christian janitors and elementary teachers and clerks and assistants and trades workers just as much as we need Christian physicians and lawyers and theologians. “Just as individuals are different, so their duties are different; and in accordance with the diversity of their callings, God demands diverse works of them.”23

Praising Ordinary Life

On several occasions, I’ve had the privilege of working as the pastor Jon Tyson’s assistant while he’s preached at my church’s conferences. On the morning I drove him back to the airport, he asked me what I did for work. I told him that I did tech services for a printer company. But I said it sheepishly, like “It’s not flashy, I know.” And he just said, “That’s the Lord’s work, mate.”

He's Australian, in case you were thrown off by the “mate” thing.

Anyways, I just thought this was a perfect response. It wasn’t as if he was trying to say, “Cheer up, mate, one day you’ll get a more prolific job.” It was a sincere, automatic response.

Ever since, I’ve tried responding in the same way (albeit, without the “mate”).

I know so many young men desperate to get a prolific ministry job or reach their mental image of a “successful” career. And it detracts so much from the actual joy of their roles in the here and now. Construction is the Lord’s work. Being a barista is the Lord’s work. All work is on the same echelon in God’s eyes.24 Every job is “ministry.”

So instead of saying “You’ll get there one day,” we should instead validate their struggle while also helping them see that what they’re doing at the moment really is the Lord’s work — and well deserving of all the honor that comes with it.

None of this is to suggest that we shouldn’t strive for excellence or fight societal corruption. A lot of reform is needed to actually create a meritocracy that works. Hard work should pay off.

Rather, this is simply to suggest that we don’t need to shoulder so much of the burden of our own destinies. There’s nothing wrong with striving to better our situation, but no matter where we find ourselves, we should aspire to joyfully “lead the life the Lord assigned to us” (1 Cor. 7:17). Like MLK Jr. said,

And so if it falls your lot to be a street sweeper, sweep streets like Rafael painted pictures. Sweep streets like Michelangelo carved marble. Sweep streets like Beethoven composed music. Sweep streets like Shakespeare wrote poetry.25

The answer to Willard’s question of what makes someone truly well-off or blessed isn’t rising to the top percentile of income, education, and social media followers. And if we treat those things like they’re truly “life to the full,” we miss out on the easy yoke Jesus offered us.

What makes someone well-off or blessed is entering into life with the Trinitarian God. That’s it. The rest is just commentary.

Luther sums this all up well: Christians “should be guided in all his works by this thought and contemplate this one thing alone, that he may serve and benefit others in all that he does, considering nothing except the need and the advantage of his neighbor.”26

One of the ways we love our neighbor well is by telling them that they matter, that they’re relevant and loved, that they’re actually needed in our community. That their role, no matter how innocuous, is necessary.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve failed to convey this sentiment. Sometimes you only notice how vital someone’s role and personality is within your community until their absence leaves a palpable void.

So I’m trying to do better at telling them, now.

Jonathan J. B. Mijs, ‘Merit and Ressentiment: How to Tackle the Tyranny of Merit’, Theory and Research in Education 20 no. 2, (2022), pp. 173-181; Jonathan J.B. Mijs, ‘Visualizing Belief in Meritocracy, 1930–2010’, Socius 4, (2018), 811805.

Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), pp. 155.

Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 3.

See Miroslav Vold, The Cost of Ambition (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2025), 13-14.

Solon, G. (1992), "Intergenerational Income Mobility in the United States," American Economic Review, 82(3), 393-408; Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2002), "The Inheritance of Inequality," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 3-30; Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014), "Where Is the Land of Opportunity! The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1553-1623; Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013); Xavier Gabaix and Augustin Landier, ‘Why Has CEO Pay Increased so Much?’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123, no. 1, (2008), pp. 49–100.

Some Colleges Have More Students from the Top 1 Percent Than the Bottom 60’, The New York Times, January 18, 2017.

Raj Chetty, John Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, and Danny Yagan, ‘Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility’, NBER Working Paper No. 23618, revised version, December 2017, opportunityinsights.org/paper/mobilityreportcards.

Belloc, M., Drago, F., Fochesato, M., & Gal-biati, R. “Multigenerational Transmission of Wealth: Florence 1403-1480,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16 no. 2 (2023): 99-129; Alfani G, Ammannati F. Long-term trends in economic inequality: the case of the Florentine state, c. 1300-1800. Econ Hist Rev. 2017 Nov;70(4): 1072-1102.

Keith Payne, Good and Reasonable People: The Psychology Behind America’s Dangerous Divide (New York: Viking, 2024), 96.

This is primarily due to the Standard Aptitude Test not actually testing innate intelligence but rather test-preparedness, and children from affluent homes receive more instruction and tutoring and are thus positioned to score better. See Andre M. Perry, ‘Students Need More Than an SAT Adversity Score, They Need a Boost in Wealth’, The Hechinger Report, May 17, 2019, brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/05 /17/students-need-more-than-an-sat-adversity-score-they-need-a-boost-in-wealth/, Figure 1; Anthony Carnevale and Stephen Rose, ‘Socioeconomic Status, Race/Ethnicity, and Selective College Admission’, in Richard B. Kahlenberg (ed.), America's Untapped Resource: Low-Income Students in Higher Education (New York: Century Foundation, 2004), pp. 130, Table 3.14.Robert H. Frank, Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochhar, ‘Trends in Income and Wealth Inequality’, Pew Research Center, Jan. 9, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality.

S. Reardon, “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap Between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations,” Whither Opportunity, (i), (2011): 91-116

Robert H. Frank, Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Michael J. Sandel, ‘Meritocracy, Education, and the Civic Project: A Reply to Commentaries on The Tyranny of Merit’, Theory and Research in Education 20, no. 2, (2022), pp. 193-199.

Alain Ehrenberg, The Weariness of the Self: Diagnosing the History of Depression in the Contemporary Age, trans. Enrico Caouette, Jacob Levi, and David Homel (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010).

Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020), pp. 3; Richard Reeves, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why it Matters, and What to Do About it (Washington, DC: Brookings Institute, 2022), pp. 32-34; Geoff Dench, Transforming Men: Changing Patterns of Dependency and Dominance in Gender Relations (London, UK: Routledge, 1998), pp. 8.

This analysis comes from political science professor Ryan Burge, while the term ‘dechurching’, though somewhat known throughout academia, was popularize for general audiences with the book The Great Dechurching, which Burge contributed extensively to; Ryan Burge, ‘Jesus Came to Proclaim Good News to the Poor. But Now They’re Leaving Church’, Research, Christianity Today, November 27, 2019, https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2019/november/income-inequality-church-attendance-gap-gss.html.

Ryan Burge, “There’s No Crisis of Faith on Campus,” Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/theres-no-crisis-of-faith-on-campus-11645714717.

Sorry for how corny this line is. Martin Luther, “The Freedom of a Christian” (1520), in Luther’s Works, 55 vols., ed. Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut Lehmann (Philadelphia and St. Louis: Fortress and Concordia, 1955–1986) 31:346.

Kathyrn Kleinhans, “The Work of a Christian: Vocation in Lutheran Perspective,” Word & World 25 no. 4 (2005): 395.

Martin Luther, “A Sermon on Keeping Children in School” (1530), in Luther’s Work, 46:246.

Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 25.

Martin Luther, “Lectures on Genesis (Genesis 8:17),” in Luther’s Work, 1535, 2:113.

Provided that they don’t subject you or others to moral atrocities.

Martin Luther King, Jr., “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” sermon delivered at Friendship Baptist Church, Pasadena, California, 28 February 1960, in The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project, Volume VI: Advocate of the Social Gospel, September 1948–March 1963, ed. Clayborne Carson, Susan Carson, Susan Englander, Troy Jackson, and Gerald L. Smith (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 398.

Luther, “The Freedom of a Christian,” 31:365

I love this so much.

I met my husband at a Christian college and he was lucky enough to have a professor tell him that just because he was passionate about God, that didn’t mean he had to be in vocational ministry (the Christian version of the American dream).

My husband switched his major from Bible studies to exercise science, which he enjoyed but ended up not being in that field either. He now co-owns a tree company with my brother in law (who quit his big successful corporate job) and they are thriving. The company not only provides well for my sister and I’s families, but also for my parents who now work for the company, and two young men who are learning the trade. We are by no means rich with money but we do well enough in that regard and are rich with the gift of time and flexibility (which in a season of toddlers and babies, is priceless).

My husband and brother in law spend all day with their employees, not only teaching them a valuable trade, but talking real life and theology constantly, and often bringing them home for dinner and more life-on-life chats. I’ve come to believe discipleship happens much more naturally and effectively in an environment like this, than in once-a-week coffee shop meetings.

They have also become a trusted presence in their community, and have had countless opportunities to serve and befriend and witness to unbelievers.

This is not at all to brag on them. They’d be the first to say the Lord has truly blessed this company and gifted us with an incredible opportunity. Just wanted to add our story to this movement towards finding what “the good life” really looks like.

If you would have told me I’d “just” be a stay at home mom and live in a rental house that’s “too small” and spend 90% of my time cooking and cleaning -LOL!! But it turns out I am often undone by the meaning and joy in my little life.

Praise God, he gave us the life we never knew to dream of.

This is such a needed balm in a culture obsessed with proving worth through outcomes. It reminds me that grace doesn’t calculate value based on productivity. Sometimes just showing up, faithfully and quietly, is the most radical thing we can do. And if the ordinary is where heaven likes to hide, then maybe the best thing we can offer the world is not our success story, but our steady presence. Thank you for putting words to that.