Why I Don't Want to Be a Billionaire (that bad)

The Fetishization of Wealth, Unused Square Footage, and Why Jesus Might've Been Right

“Billionaires are like the popular kids in high school. You hate them while secretly wanting to be them.”1

Our culture fetishizes money, especially large amounts of it.

Take for example the very funny SNL sketch “Zillow." It features a montage of characters getting alone with their laptops, but in lieu of porn, scroll through Zillow photo galleries of the most expensive houses. “Sex not doing it for you anymore? Try Zillow!”

Zillow browsing is just one example of billionaire daydreaming; but weirdly enough, if you look beyond the pastime, you'll find billionaires may not have it as good as you think.

Here's what I mean:

The square footage of the average home almost doubled in the last half century. But in that same timeframe, the average household went from around 3.51 persons to a little under 2.42 – and single person households increased more than fivefold.3

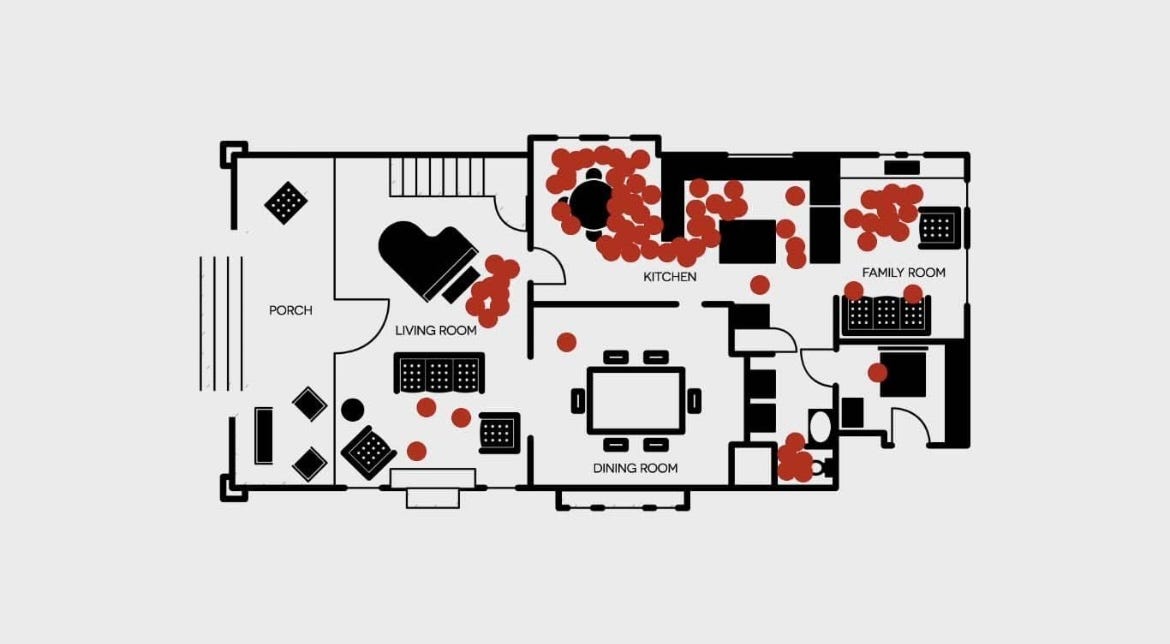

Then another study found that, when home and awake, the average person spends 68% of their time in the kitchen, and the remainder is spent between the living room and bathroom.4

Meaning, on average, people only use around 600 square feet of space.

Extra space beyond that inevitably becomes storage, accessory, or aesthetic.

Billionaires are more capable of buying those 8,000+ square foot Zillow homes, but they’re not any more capable of using them.

Worse yet, they also have less time to enjoy them.

On average, millionaires work longer hours than the middle class,5 and billionaires work even longer hours than millionaires.6

One was quoted saying, “Most people work 9-to-5. I work 95.”7

Which translates to 13.5-hour workdays seven days a week – and also creates a paradox:

Most people want money so they can have more freedom and opportunity, but those who get lots of money end up with far less free time than those with an average amount of it.

Turns out, public intellectual Biggie Smalls may have been spot on when he said, “More money, more problems.”

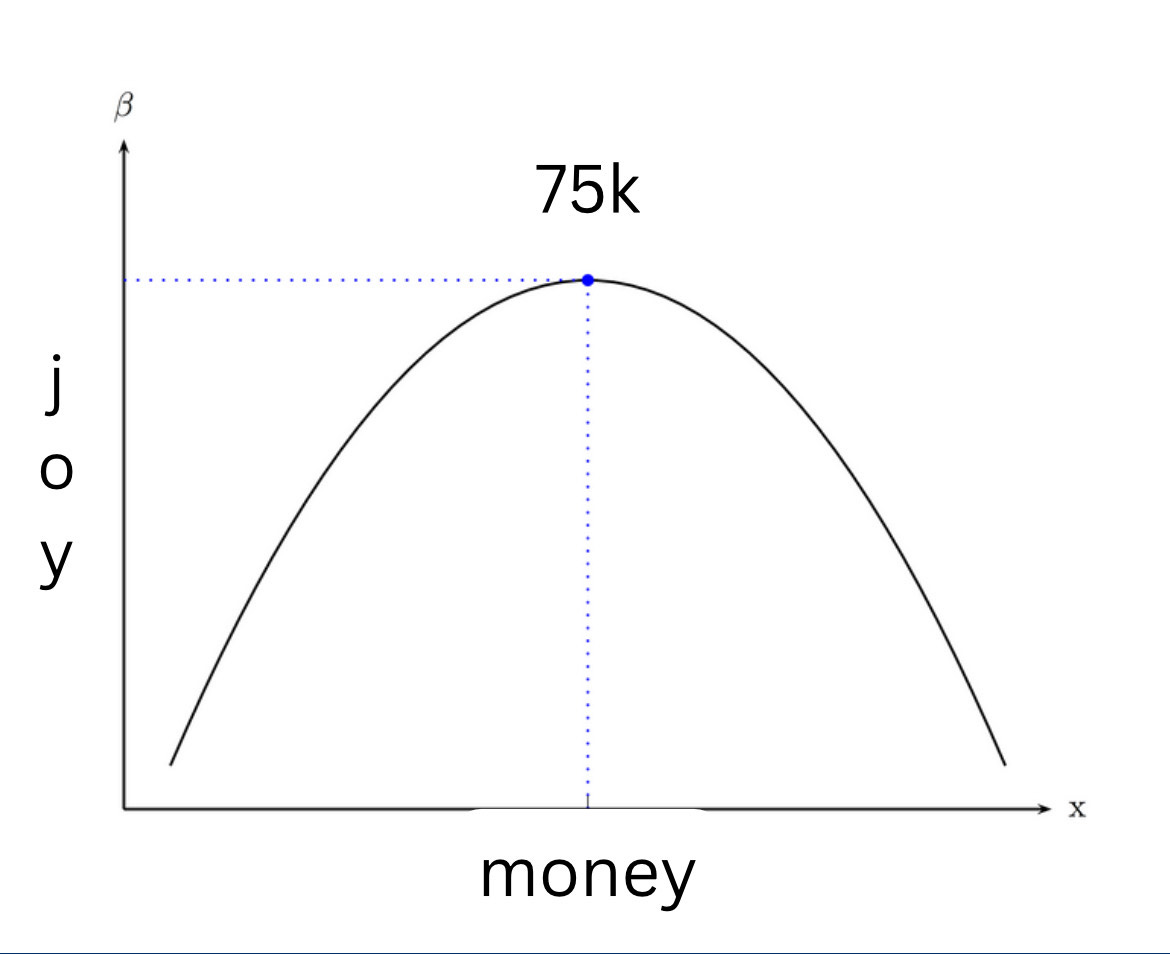

At a certain point, more money just creates more clutter. Psychologists call this “The Inverted-U-Curve.”8

According to piles of research and meta-analyses (studies of studies) it was found that more money does, sort of, lead to more happiness – but only up to a certain point.

And that magical point is a 75,000-dollar yearly income (around 101k now, adjusted for inflation).9

When you’re below the 75,000-dollar mark, earning more money gives more satisfaction.

i.e., You work 40 hours, get paid, and get satisfaction from your pay; you get a raise, work another 40 hours, and get more satisfaction than before.

But then one day you get another raise, work another 40 hours, and the satisfaction isn't as high.

In fact, there’s more pleasure in the raise from $70,000 to $74,999 than from $74,999 to $80,000.

Pre-75k, overall well-being tends to increase in correlation with money.

Post-75k, well-being stops correlating with money.

Further, sometimes happiness can start decreasing with pay raises. As a large-scale study conducted by Tim Kasser between 140 psychologists and their patients found, the more highly people rank wealth and material possessions on their list of values, the more likely they are to be anxious, discontent, depressed, and even physically ill.10

That said, not having money sucks — a lot.

But once you have enough, it loses its thrill.

The point being:

Too little of a good thing is a bad thing, but too much of a good thing is also a bad thing.11

Take food for example. It’s something that requires moderation. There comes a point when you literally cannot eat more.

But money is different.

Adam Smith, the father of economic theory, wrote, “The desire for food is limited in every man by the narrow capacity of the stomach; but the desire for money, convenience, dress, equipment, ornaments, and furniture seems to have no limit.”12

Like the writer of Ecclesiastes says,

“Whoever loves money will never have enough. Whoever loves wealth will never be satisfied with income. For it's meaningless – money can't keep you warm at night. You may as well chase after the wind.” (5:10-11, my translation)

If billionaires can teach us anything, it’s that there doesn’t seem to be a point where wealth makes you “full.”13

Like any other addiction, the money-obsessed keep going and going until they're exhausted, often alienating friends and family in the process.

When the mogul John Rockefeller, who was at one point the richest man in history, was questioned by a reporter about how much money would be enough, Rockefeller cleverly (and hauntingly) replied, “just a little bit more.”14

To me, that doesn’t sound like a testament to the perks of riches; it sounds like an addict who’s let their addiction rule them.

As that one line from Sermon on the Mount goes: “No one can serve two masters. For either he will hate one and love the other, or be devoted to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and money” (Matt, 6:24-25).

If money becomes more than a tool, it becomes a master.

It’s almost like Jesus was right.

John Green, The Anthropocene Reviewed: Essays on a Human-Centered Planet (New York: Dutton, 2023), 30.

Steve Adcock, “This Study Suggests That You’re Wasting a Ton of Home Space,” think.save.retire, April 21, 2021, www. thinksaveretire.com/.

USA Facts Team, “How Has the Structure of the American Household Changed Over Time?” USA Facts, November 1, 2023, https://usafacts.org/articles/state-relationships-marriages-and-living-alone-us/.

Statistics from a UCLA study popularized by the WSJ article “The Stuff of Families,” https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1000142405270230.

Hillary Hoffower, “17 Things Millionaires Do Differently,” Business Insider, December 27, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/millionaire-habits-how-to-build-wealth-time-energy-money-2019-4.

Morgan Housel, The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness (New York: Harriman House, 2020), 37-38.

Kathleen Elkins, “Self-Made Millionaires…” CNBC, June 15, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/amp/2017/06/15/self-made-millionaires-agree-on-how-many-hours-you-should-be-working.html.

Adam Grant & Barry Schwartz, “Too Much of a Good Thing: The Challenge and Opportunity of the Inverted-U,” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6 no. 1 (2011): 61–76.

Though recent (un-peer reviewed) research may suggest that the amount of necessary income to achieve contentment is dependent on location. For the original study, see Daniel Kahneman & Angus Deaton, “High Income Improves Evaluation of Life but Not Emotional Well-Being,” Psychological and Cognitive Science 107 no. 38 (2010): 16489-16493. See also Andrew T. Jebb, Louis Tay, Ed Diener, & Shigehiro Oishi, “Happiness, Income Satiation and Turning Points Around the World,” Nature Human Behaviour 2 no. 1 (2018): 33-38.

Tim Kasser & Allen Kanner, ed(s). Psychology and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2003) 3–6; Tim Kasser & Richard Ryan, “Further Examining the American dream: Differential Correlates of Intrinsic and Extrinsic goals,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 907–914.

This point doesn’t just apply to money. Apparently, our neural makeup tends to enjoy average amounts of most anything but then gets disturbed whenever it drifts toward extremes. See Georg Northoff & Shankar Tumati, “Average is Good, Extremes Are Bad” – Non-Linear Inverted U-shaped Relationship Between Neural Mechanisms and Functionality of Mental Features,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104 (2019): 11-25.

Econ 101 & 102 did come in handy. Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1756) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); See also Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (New York: Vintage, 1985).

Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), book 1 (New York: Modern Library, 1994); Hauser, The Psychology of Money, 37-42.

I’ve heard this quote a million times, but I’ve never found an accurate source. I once heard it came from a book or collection of interviews called Conversations with Rockefeller, but I honestly can’t even track the book down. So just take the “quote” part with a grain of salt.

This reminds me of Tolstoy's short story "How much land does a man need?" That human desire for just...a little bit...more...is a deeply-rooted one, I think.

On a personal note, our family of 8 lives in 1500 square feet of space. Would a little more be awesome? Definitely. But I try to be content with what we have because when I am being completely honest with myself (and not influenced by the house-porn of Instagram) it really, truly is...enough.

I never encountered unbelievable wealth until I went to law school, where I knew (not closely) several people whose parents were billionaires. I can’t say anything about that lifestyle appeals to me. There’s a reason none of them seem happy.

To paraphrase Joseph Heller, true wealth is knowing when you have enough.