Why Theology Needs Comedy

How Humor Strengthens Our Faith, How They Got Separated in the First Place, and Why It Matters

Audio voiceover available here for paid subscribers!

Broken Clocks & Academic Irreverence

I kept getting my papers marked down, which was understandable in light of the context but discouraging for that same reason. This was part and parcel of a comedy nerd in academia.

I’ve been watching SNL since the womb. In middle school, I memorized a 25-minute Brian Regan special in case I ever needed to recite it in its entirety. In recent years, I’ve found John Mulaney’s five standup specials unintentionally imprinted in my memory just from repeated viewings.

This lifetime of comedy appreciation has taught me that most humor occurs through a two-step punch. First, the comedian lures you into a familiar, relatable situation. Then comes the surprising turn – when they say or do something absurd that breaks the mold – usually unveiling the humorous undertones to the mundane familiar. Or put another way, “Humor is what happens when we’re told the truth more quickly than we’re used to.”1

This also explains my habit of putting jokes into unexpected places, including academic papers.

I quoted John Calvin and commented in the footnote, “Even a broken clock is right twice a day.” I knew my professor disliked Calvin, so I thought he might enjoy some levity amidst a stack of quasi-erudite grad papers rehashing trinitarian dogma.

But even though the paper was unflawed by the rubric’s standard, I got three points marked down. The comment read, “This is an academic paper.”

My professor was right, of course; but what disappointed me was the in-built assumption that an academic paper couldn’t have jokes. I’ve written dozens of scholarly articles littered with 2-3 jokes apiece, and only 2-3 jokes ever got to see the light at the end of the peer-review (somehow the one about erectile dysfunction as an illustration of the problem of evil slipped by).

I never held it against my professors, just the TA’s. It’s almost accepted knowledge that theology and comedy are mutually exclusive. As the theologian Graeme Garrett lamented, “Theology is a sombre matter. To the humorist it has little or nothing to say, and from the humorist — to its loss — it seems to have nothing to learn.”2 Philosopher Alenka Zupančič even called comedy “anti-theological.”3

All of which is unfortunate because I think God is extremely funny. Think about giraffes or hippos or “baboons with bright red asses” or that He created us with the function to not only laugh but laugh so hard that we choke and liquid falls out of our eyes. Or even consider that Jesus was playful enough that children wanted to crowd around Him (Matt. 10:13-16). To insist that God is perpetually in a state of deadpan seriousness just doesn’t seem accurate.

Anyway, a thesis would probably help, so here: even though theology and comedy are often painted as incompatible, they’re not. While theological spaces have earned a reputation as notoriously unfunny, this reputation was born out of historical and cultural influences rather than universal theological truisms. If we don’t make room in our theology for comedy, our theology gets stale. This applies to academia, churches, and your dating life. Let’s start by asking

what is comedy?

It’s difficult to understand what makes something “funny.” As Charlotte’s Web author E.B. White wrote, “Humor can be dissected as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind.”4 The more humor is explained, the less humorous it becomes, and the less we’re able to understand why we were laughing in the first place. It’s why philosopher D.H. Munro called laughter “one of the unresolved problems of philosophy.”5

And yet humor is an inescapable part of being human. From the time we’re infants giggling at parental buffoonery until we’re old folks chuckling during Bingo, laughter is an unavoidable reflex. Even situations that seem vacuum sealed of comedy somehow contain a failsafe that helps laughter rebound—as in when 50 things go wrong in one day and rather than scream we simply laugh at our sheer horrible luck.

Regardless of the “why” behind humor, we do know it’s a useful social glue. It makes human connection unique from the interactions between animals, such as dogs or porcupines. Mice, even. After studying 1,200 instances of naturally occurring laughter, psychologist Robert Provine discovered that only 20% of laughs were because of conventional humor.6 80% of laughs happened in response to bland comments.

This is because we “laugh to show someone that we want to connect with them – and our companions laugh back to demonstrate that they want to connect with us.”7 Basically, most laughs happen because we’re in sync with others and want to match their energy and body language.8

Jokes also help alleviate anxiety. They’re an antidote for situations with too little levity. It’s often taken too far of course, hence the common, “Okay, now let’s be serious.” But strategic comedic exchanges can build stronger connections between people while downplaying everyone’s nerves.

Now let’s talk about more stuff, like the relationship between

theology and comedy.

“Human existence may be defined as a running interplay between seriousness and laughter, between sacred concerns and comic interludes.” — Conrad Hyers

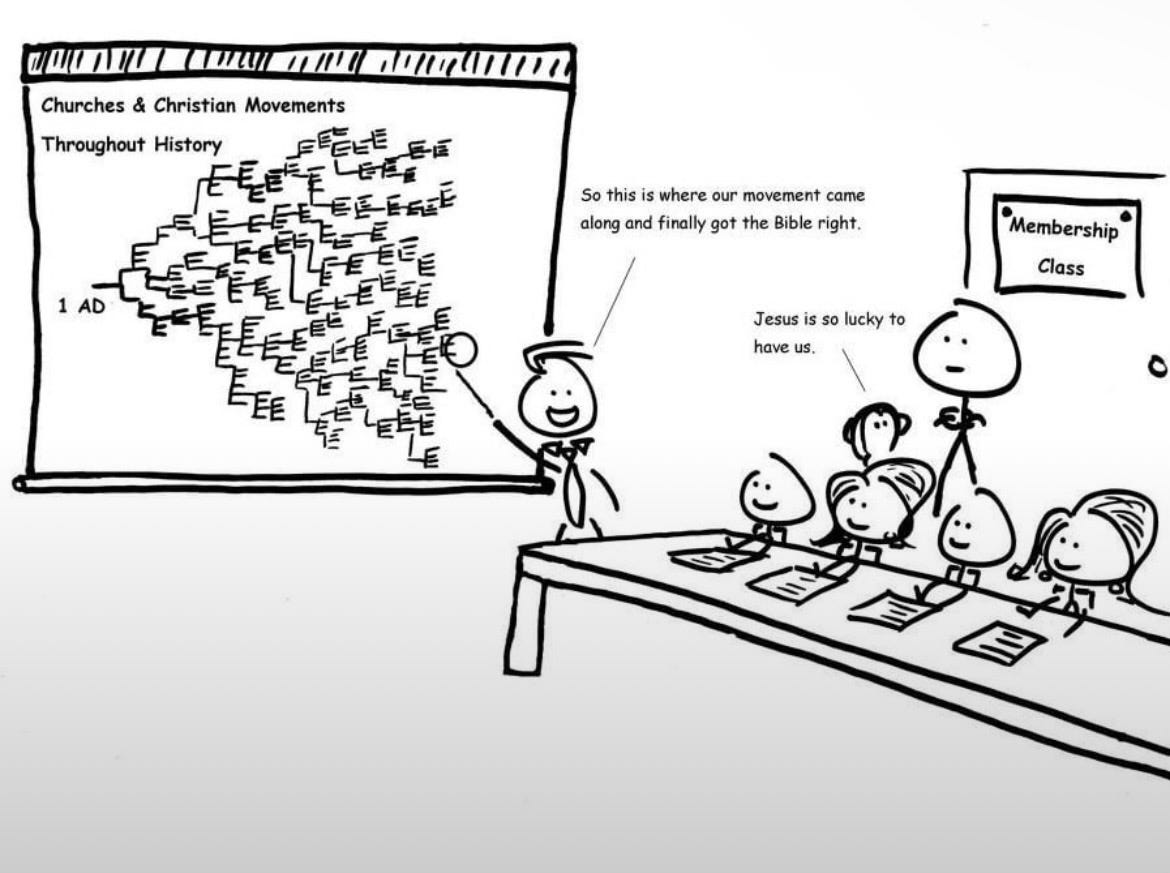

For many, theology is the opposite of comedy. Some research even supports a natural segregation between religious and comedic thinking.9 When psychologist William Holcomb ran an experiment asking subjects to produce humorous responses to various hypothetical situations, he found that religious fundamentalists performed the worst out of any demographic.10 Apparently, your religious beliefs — whether you’re evangelical, atheist, or doing Tom Cruise’s thing — have a direct correlation on your sense of humor.

But even though they seem different on the surface, they do have one strong correlation: they’re the two main ways to react to the unexplainable.11 For example, when we encounter incongruity (i.e., strange, surprising, or mysterious things that feel out of place, like an insane haircut on the subway, a strange exchange with a bank teller, a dog going berserk over a new scent) humor allows us to make light of it. Rather than going into a stoic detective mode, putting every engagement on pause as we pummel reality into coughing up explanations, we can just laugh and move on.

But laughter doesn’t satisfy forever. The dull ring of unanswered questions about the universe eventually gets too loud. So when laughter fails to do the trick, our curiosity often turns to religion to fill in the gaps.

Basically: comedy lets us laugh off the unexplainable; religion reminds us that the unexplainable won’t crush us. While laughter helps us dismiss light-hearted absurdity, religion helps us metabolize complex mysteries with wonder. Jokes break down our need for control over reality; theological rumination highlights our lack of control in a way that shapes that non-control into something beautiful.

G.K. Chesterton said something similar,

Life is serious all the time, but living cannot be. You may have all the solemnity you wish in choosing your neckties, but in anything important such as death, sex, and religion, you must have laughter or you will have madness.12

The neuroscientists Joanna Collicutt and Amanda Gray even found that the comedic and the theological both tap into the brain’s sense of transcendence.13 So despite some beliefs that comedy and theology don’t mix, there’s a good chance they’re really just different extremes of the same plane.

So in reality, their segregation is more cultural than natural. As for where this cultural stuff came from, you can blame the

Puritans, Pioneers, and (P)Victorians.

Though it’s a bit of a generalization, theologian Fred Layman traces the Christian trepidation about humor back to the Puritans, noting that many acted as if the chief goal in this world was making sure they only found joy in the next. “Puritans did not joke when they preached…they preached against jokes.”14 As another scholar put it, “Critics unjustly trace to Jesus the depressing graveyard atmosphere that sometimes haunts the church. The men who really killed joy wore pointed three-cornered hats and buckled shoes.”15

Beyond Puritanism, there’s also our Victorian inheritance — which comes packaged with disdain toward vulgarity, fear of lax mannerisms, and the association of humor with low-class incivility. Some have even insisted that Western Christianity has been more influenced by Victorianism than Jesus.16

It’s not all their fault; plenty of other theologians throughout church history also waged war against humor.17 NT scholar Harold Hoehner suspects a lot of this hesitation comes from a skewed interpretation of Ephesian 5:4’s warning about “crude joking.” Hoehner argues this warning most

likely refers to jesting that has gone too far and has become sarcastic ridicule that cuts people down and embarrasses others who are present. It is humor in bad taste — at someone's expense…This does not mean that Christians must be humorless, but they must be controlled.18

On top of that, to insist that jokes don’t mix with Christianity is to ignore

the humor of Scripture.

D. Elton Trueblood, the scholar behind The Humor of Christ, wrote,

The widespread failure to recognize and to appreciate the humor of Christ is one of the most amazing aspects of the era named for Him. Anyone who reads the Synoptic Gospels with a relative freedom from presuppositions might be expected to see that Christ laughed, and that He expected others to laugh, but our capacity to miss this aspect of His life is phenomenal.19

Incongruities are a big reason that we laugh, and Jesus Himself was the “divine incongruity.” That God became man, lived as a blue-collar teknon from the low-class Galilee, revealed Himself as the brilliant and miracle-working Messiah, and went down in history as the absolute center of it is just brimming with humor.

There’s even shades of comedy in His crucifixion: He endured the most humiliating death imaginable but managed to turn the humiliation toward Satan, making a “public spectacle” out of the powers of darkness (Col. 2:15). For this reason, many sects of the Greek Orthodox church and the Slavish tradition still gather on the Monday after Easter for the purpose of trading jokes. For them, the empty tomb is the best-standing, longest-running joke in history, and so they honor God’s victory by continuing the joke.20

And Bible humor extends way beyond Christ’s. There are talking donkeys, Dagon statues toppled over, armies overthrown through torches and jugs, and stubborn humans humbled by whales. All of which illustrate the distinct

theological function of humor.

Humor isn’t an unnecessary appendage to human life. Laughter is one of God’s physiological gifts that helps alleviate neurological afflictions on this side of the New Creation.

We can see this in Abraham and Sarah’s story. When God tells the elderly couple they’re going to have a child, Sarah laughed at the ridiculousness of it (Gen. 18:12). But when Sarah actually had the promised child, she laughs again (Gen. 21:6-7). The first laugh is out of cynicism, born from her years of tearful shattered dreams of motherhood; the second laugh was out of wonder that God was even capable of bringing about such kindness.

As the theologian Jürgen Moltmann wrote, “God weeps with us so we may one day laugh with him.”21

When we’re dragged down by pain, heartache, injustice, unfairness, and uncertainty, humor provides a safety net. Each laugh comes stapled with a sense of wonder, relief, and joy that momentarily affords us strength to tolerate the present.

Writing about his experience in Auschwitz, Viktor Frankl said, “Humor was another of the soul's weapons in the fight for self-preservation…It is well known that humor, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and ability to rise above any situation, even only for a few seconds.”22

If we neglect laughter, we neglect one of God’s many gifts for processing the discontent of not yet inhabiting the fullness of His kingdom.

Or, in Frederick Buechner’s words, “Laughter comes from “as deep a place as tears come from”; it comes “out of the darkness…not as an ally of darkness but as its adversary…its antidote.”23

God weeps with us so we may one day laugh with Him.

Okay, on to a

potentially overly optimistic plan for reintegrating theology and comedy.

Theology and comedy aren’t incompatible. They can even critique and refine one another.

For example, over the years I’ve noticed that some of my favorite theologians add little humorous comments in their writing every now and then.24 But the comedy doesn’t drag down the theology — in some ways, it even enhances it. It’s almost like over-seriousness dresses theological discourse into a stuffy suit two sizes too small, and the humor adds a frequency of humility and self-awareness that undresses the façade.

An aroma of self-importance swells up when humans – very fallible, non-messianic humans – make exact explanations about God or draft overconfident WWJD scenarios. “For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are God’s ways higher than ours and His thoughts than our thoughts,” we say one day while declaring, “This is who the true Jesus would vote for in this election” the next.

Now, sadly, part of doing theology involves having opinions. But keeping humor in our writer’s toolbox helps pair down some of the “I’m right, now deal with it,” arrogance common to the knowledge trades. So for example, after going on a roll with a long argument, adding something like, “But what do I know?” provides everyone some breathing space. Also, something funnier would probably work much better.

This kind of lightheartedness connects to a reader’s humanity while reminding them of their own hubris – that they also often think they know exactly what God would do were He them or they Him.

Which demonstrates another one of comedy’s theological powers: how it can point out moral inconsistencies without direct confrontation. Humor can deliver audiences an actual criticism while allowing them to receive it with a laugh as opposed to a slap in the face. Comedy is exhortation wearing goofy lipstick, unveiling hypocrisy as roughly as a throw pillow. So in a roundabout way, comedy accentuates how humans can better inhabit their moral framework, which is one of the central tasks of theology.25

Theologian Doris Donnelly drafted some advice for reintegrating humor and theology:

Retrain the imagination to find humor in the ordinary incongruities of life.

Spend time with people who have a sense of humor.

Use laughter to deflect anxiety and ease the stress of getting defensive.

Take a five-to-ten-minute laugh break every day.

Celebrate humorous insights among theologians and clergy so as to encourage more humor in their fields.

Look for humor in the Scriptures.26

I agree. But I’d also add that we should destigmatize skepticism about humor in academic settings. I wrote a whole academic paper about the psychological benefits of using humor in Christian academia. And since it passed the peer-review, this means it’s authoritative.

Part of the concern is due to the still widespread belief that humor is unintelligent, childish, or whatever the opposite of distinguished is (“in” or “un” or “non-”distinguished?). But the idea that humor is unsophisticated is a total myth. Just look at the alma maters of the average SNL writer: Princeton, Harvard, NYU, and so on.

The psychologists Gil Greengross and Geoffrey Miller have even shown that humor is correlated with higher IQ. Others have argued that Humor Intelligence (HI) should be takes as seriously as IQ and EQ.27 To locate the incongruities that surround us and then think of something clever enough to produce laughter is a highly perceptive skill. Even the lowest-brow humor has hints of high-brow. This is why Mark Twain said, “Humor is a way to show you’re smart without bragging.”28

While humor may always go against the protocol in some settings, we shouldn’t overlook the upsides. Both theology and comedy are accessed through transcendence and incentivize more transcendence. A humorous, playful mind supplies a childlikeness that allows us to engage theology with wonder and joy.

My data to support this is that it works, for me.

Ok that was a lot of writing, so I’ll end, which is one of the hardest parts about writing an essay, I think, because figuring out the perfect end is incredibly difficult, and even though ending on “Amen” is a pretty solid choice, it can come across a little cliché or derivative, so I’ll instead just end with one of my favorite quotes from Madeleine L’Engle,

“I hope that I will never forget the salvific power of joyful laughter.”29

Amen.

George Saunders, The Braindead Megaphone: Essays (New York: Riverhead Books, 2007), 12.

Graeme Garrett, ‘“My Brother Esau Is a Hairy Man”: An Encounter Between the Comedian and the Preacher’, Scottish Journal of Theology 33 (1980), 240.

Alenka Zupančič, The Odd One In: On Comedy. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008).

E. B. & Katherine S. White, ed(s). A Subtreasury of American Humor (New York: Tudor Publishing Co, 1945), xvii.

D.H. Munro, Argument of Laughter (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1963),13. These past three quotes are each found in Fred D. Layman, ‘Theology and Humor’, The Asbury Seminarian 38 no. 1 (1982): 3.

Robert R. Provine, ‘Laughter’, American Scientist 84 no. 1 (1996): 38-45; Robert R. Provine, ‘Laughing, Tickling, and the Evolution of Speech and Self’, Current Directions in Psychological Science 13 no. 6 (2004), p. 215-18.

Charles Duhigg, Supercommunicators: How to Unlock the Secret Language of Connection (New York: Random House, 2024), p. 113; see also Chiara Mazzocconi, Ye Tian, and Jonathan Ginzburg, ‘What's Your Laughter Doing There? A Taxonomy of the Pragmatic Functions of Laughter’, IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 13 no. 3 (2020), p. 1302-1321; see also Frans de Waal, Our Inner Ape (London, UK: Granta, 2005), p. 56.

Christopher Oveis, et al., ‘Laughter Conveys Status’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 65 (2016), p. 109-115; Michael J. Owren & Jo-Anne Bachorowski, ‘Reconsidering the Evolution of Nonlinguistic Communication: The Case of Laughter’, Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 27 (2003): 183-200; Jo-Anne Bachorowski & Michael J. Owren, ‘Not All Laughs Are Alike: Voiced but Not Unvoiced Laughter Readily Elicits Positive Affect’, Psychological Science 12, no. 3 (2001), p. 252-57; Robert R. Provine & Kenneth R. Fischer, ‘Laughing, Smiling, and Talking: Relation to Sleeping and Social Context in Humans’, Ethology 83, no. 4 (1989), p. 295-305.

Vassilis Saroglou, “Religion and Humor: An a priori Incompatibility?” International Journal of Humor Research 15, no. 2 (2002): 201; Vassilis Saroglou & Jean-Marie Jaspard, “Does Religion Affect Humour Creation? An Experimental Study,” Mental Health, Religion & Culture 4 no. 1 (2002), 33–46; Vassilis Saroglou, “Religiousness, Religious Fundamentalism, and Quest as Predictors of Humor Creation,” The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 12 no. 3 (2002), 177–188.

William R. Holcomb & William S. Ivey. “Religious Fundamentalism, Humor, and Treatment Outcomes in Individuals in Court-Mandated Substance Abuse Outpatient Treatment,” Psychological Reports 120 no. 3 (2017), 491-502; K.H. Ott & B. Schweizer, “Does Religion Shape People’s Sense of Humour? A Comparative Study of Humour Appreciation Among Members of Different Religions and Nonbelievers” The European Journal of Humour Research 6 no. 1 (2018): 12–35.

This is a central point found throughout Peter L. Berger, Redeeming Laughter: The Comic Dimension of Human Experience (Boston, MA: De Gruyter, 2014); see also Reinhold Niebuhr, “Humour and Faith,” in The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr: Selected Essays and Addresses, ed. Robert McAfee Brown (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 49-60

G. K. Chesterton, Lunacy and Letters, ed. Dorothy Collins (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1958), 97.

Joanna Collicutt & Amanda Gray, ‘“a merry heart doeth good like a medicine”: Humour, Religion and Wellbeing’, Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15 no. 2 (2012): 759–778.

Paul K. Jewett, “The Wit and Humor of Life,” Christianity Today 3 (1959): 7.

David A. Redding, “God Made Me to Laugh,” Christianity Today 6 (1962): 3.

Karen Swallow Prior, The Evangelical Imagination (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2023), 13-15.; Timothy Larsen, interview by Albert Mohler, “A Closer Look at Victorian Christianity: A Conversation with Historian Timothy Larsen,” Thinking in Public, November 11, 2011, https://albertmohler.com/2011/11/21/a-closer-look-at-victorian-christianity-a-conversation-with-historian-timothy-larsen.

Including Basil of Caserea (Basil of Caesarea, Letter 22: On the Perfection of the Life of Solitaries, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3202022.htm.), Ammonius (Ingvild Saelid Gilhus, Laughing Gods, Weeping Virgins: Laughter in the History of Religion (London: Routledge, 1997), 69. See also Duncan Bruce Reyburn, “Laughter and the Between: G. K. Chesterton and the Reconciliation of Theology and Hilarity,” Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics 3 (2015): 20.) Clement of Alexandria (John Kaye, Some Account of the Writings and Opinions of Clement of Alexandria (London: J. G. & F. Rivington 1835), 77.), John Chrysostom (John Chrysostom, Concerning the Statues, Homily, XV.), and Saint Benedict (St. Benedict, The Rule of St. Benedict: In Latin and English with Notes (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1981), 7, 59-61; Gilhus, Laughing Gods, 69.).

Harold W. Hoehner, Ephesians: An Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2002), 101.

D. Elton Trueblood, The Humor of Christ (London, UK: Libra, 1964), 15.

Conrad Hyers, “Easter Hilarity,” in And God Created Laughter: The Bible as Divine Comedy (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1987), 24-28; Doris Donnelly, “Divine Folly: Being Religious and the Exercise of Humor,” Theology Today 48 (1992): 385.

Quoted in Daniel Silliman, “Died: Jürgen Moltmann, Theologian of Hope,” Christianity Today, June 4, 2024. https://www.christianitytoday.com/2024/06/moltmann-obit-theology-hope/.

Viktor E. Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2006), 43.

Frederick Buechner, Telling the Truth, 56.

The ones who do this best are, I think, Kierkegaard, C.S. Lewis, G.K. Chesterton, Dallas Willard, and even Charles Spurgeon every now and then.

Nancy Murphy, ‘Philosophical Resources for Integration’, in Alvin Dueck & Cameron Lee, C. (Eds.), Why Psychology Needs Theology: A Radical-Reformation Perspective (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005), 10-18; See also David Kelsey, The Uses of Scripture in Recent Theology (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), 159.

Donnelly, “Divine Folly,” 397-398.

Gil Greengross & Geoffrey Miller, “Humor Ability Reveals Intelligence, Predicts Mating Success, and is Higher in Males,” Intelligence 39 no. 4 (2011):188-192; Alan Feingold & Ronald Mazzella, “Psychometric Intelligence and Verbal Humor Ability,” Personality and Individual Differences 12 no. 5 (1991): 427-435; Maurice E. Schweitzer, “Humor Intelligence: Production, Perception, Prediction, and Measurement,” Current Opinion in Psychology, 55 (2024): 101722.

Like many clever phrases attributed to Twain, there’s no proof that he actually said this.

Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water, 124

Solemn seriousness is a symptom of spiritual malaise. Those afflicted with that disorder find it all too easy to take offense. As I was reflecting on your post, a quote from C.S. Lewis in the preface to The Screwtape Letters came immediately to mind. Turned our Lewis was quoting Chesteron. Here is the Chesterton quote in it's context which probably needs to be carved in stone in all theology lecture halls:

The swiftest things are the softest things. A bird is active, because a bird is soft. A stone is helpless, because a stone is hard. The stone must by its own nature go downwards, because hardness is weakness. The bird can of its nature go upwards, because fragility is force. In perfect force there is a kind of frivolity, an airiness that can maintain itself in the air. Modern investigators of miraculous history have solemnly admitted that a characteristic of the great saints is their power of “levitation.” They might go further; a characteristic of the great saints is their power of levity. Angels can fly because they can take themselves lightly. This has been always the instinct of Christendom, and especially the instinct of Christian art… In the old Christian pictures the sky over every figure is like a blue or gold parachute. Every figure seems ready to fly up and float about in the heavens. The tattered cloak of the beggar will bear him up like the rayed plumes of the angels. But the kings in their heavy gold and the proud in their robes of purple will all of their nature sink downwards, for pride cannot rise to levity or levitation. Pride is the downward drag of all things into an easy solemnity. One “settles down” into a sort of selfish seriousness; but one has to rise to a gay self-forgetfulness. A man “falls” into a brown study; he reaches up at a blue sky. Seriousness is not a virtue. It would be a heresy, but a much more sensible heresy, to say that seriousness is a vice. It is really a natural trend or lapse into taking one’s self gravely, because it is the easiest thing to do. It is much easier to write a good Times leading article than a good joke in Punch. For solemnity flows out of men naturally; but laughter is a leap. It is easy to be heavy: hard to be light. Satan fell by the force of gravity. (G.,K. Chesteron, Orthodoxy. Found on The Habit blog from 2011)

"Humor isn’t an unnecessary appendage to human life. Laughter is one of God’s physiological gifts that helps alleviate neurological afflictions on this side of the New Creation." I totally have experienced this in the most difficult of circumstances. Laughter helps to lift the spirit, lighten the load, and works to remind ourselves that our ultimate reality is a comedy, not a tragedy when all things are revealed at the coming of Christ..