How Science Became Faith's Horror Story (and why science isn't all that scary)

A Non-Exhaustive and Non-Nerdy Sketch of How Science Can Assist Spiritual Knowledge

tl;dr: science and faith are usually seen as incompatible when, in reality, they’re just asking different questions. In some ways, science can even be a helpful tool for faith.

1. The Ghost Story of Biological Sciences

35% of Christians think science contradicts their faith, and over half feel apprehensive about engaging in scientific dialogue.1

This can make for environments where scenarios such as, “Your child wants to go to Stanford to study evolutionary biology,” get treated like campfire ghost stories.

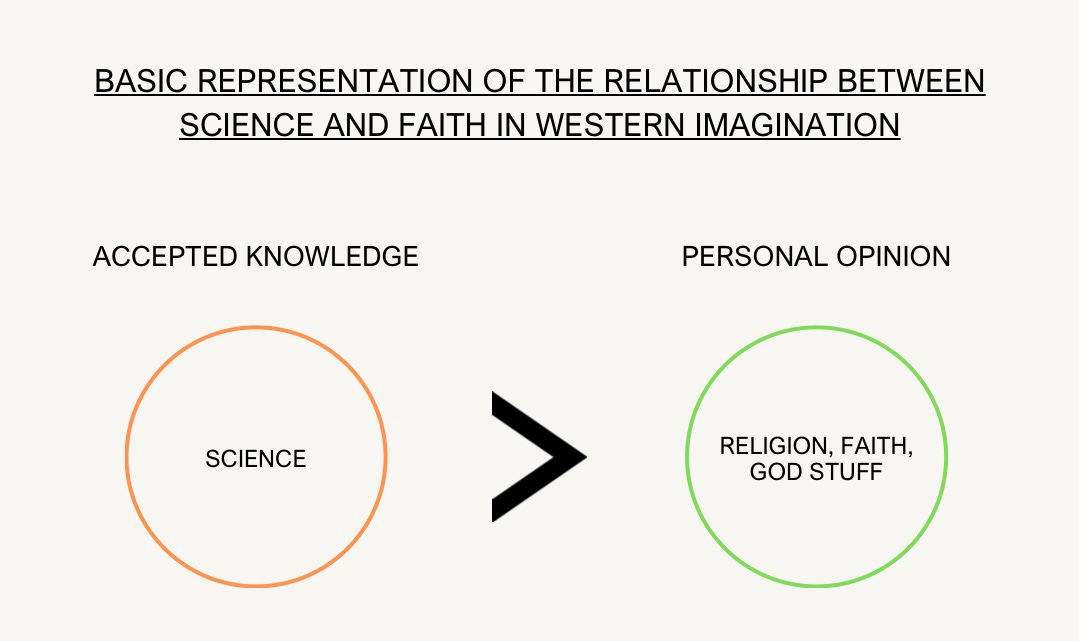

Which isn’t entirely unreasonable. In the Western popular imagination, science and faith are incompatible. So baseline fears about the consequences of studying science are understandable.

But there’s a chance that the deeper worry underlying this fear is that spiritual knowledge isn’t on par with “academic fact.”

I notice this pretty frequently in church communities: compartmentalizing the questions that can be answered by the scientific method in the “accepted truth” category, while placing God and Bible stuff in the “personal opinion” category.2

But the tension this creates is both strange and anxious.

As the missiologist Lesslie Newbigin described it,

No faith can command a man's final and absolute allegiance if he knows that it is only true for certain places and certain people. In a world which knows that there is only one physics and one mathematics, religion cannot do less than claim for itself a like universal validity.3

If our faith is true, and gravely concerned with unveiling and embodying the truth (John 8:31-32; 14:6-7; 17:17), then carrying low-grade paranoia about how spiritual knowledge is inferior to science will congest our conforming to its truth.

But thankfully, faith and the sciences are much more symbiotic than people give them credit for.

They’re not really “incompatible”; they just have different interests that cause them to ask different questions.

2. Personal Reasons for Dabbling in Science

In my own writing — which, at least, in my mind, is in the spiritual formation genre — I cite a lot of psych studies, neuroscience, and sociological dogma. I don’t have an exact ratio, but I’d guess it’s around half and half between theologians and mystics on one end and social scientists and secular philosophers on the other.

This isn’t because I value fMRI scans over spiritual knowledge. It’s because I think that discoveries about the human condition help illuminate more about how God designed us and our universe.

They’re not more authoritative than Scripture; they’re just a tool for understanding ourselves and reality.

Theologian Francis Schaeffer offered this helpful distinction: just because God communicates truly through Scripture doesn’t mean that God communicates exhaustively through Scripture. The Bible is true from front-to-back; it just doesn’t say every true thing.

God then compensates this non-exhaustive sketch of reality by wiring us with both the rationality and curiosity that causes us to “explore and discover further truth concerning creation.”4

Several early Jewish rabbis and Christian theologians also picked up on this. As Origen put it in the 2nd century:

A desire to know the truth of things has been implanted in our souls and is natural to human beings…When our eye sees the work of a craftsman, especially if the object is well made, at once the mind burns with desire to know what sort of thing it is, how it was made and for what purpose. Even more does this mind burn with desire and ineffable longing to know the design of those things which we perceive to have been made by God…For as the eye by nature seeks light and our body instinctively craves food and drink, so our mind nurtures a desire to know the truth of God and to learn the causes of things.5

Origen’s description is beautiful because it connects the desire for truth with the confidence that this desire inevitably winds us back in God’s presence.

The man who founded Dyson (kinda random, I know) also noted this phenomenon: “The more I examine the universe and study the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense must have known we were coming.”6

Although it’s not a flawless guarantee, scientific study often points us back to God simply because of the way both truth and creation point to Him (Psalm 19:1-6; Rom. 1:19-20).7

This might be partly why, despite popular assumptions, demographics with more education are more likely to attend church.

There’s a stat that’s been floating around since 2019 that says that 7 out of 10 high school students will leave the faith during college.8 But it wasn’t accurate then and still isn’t now.

As more recent research has shown, there isn’t any dramatic change in religious beliefs between college commencement ceremonies and graduation.

Nowadays, proportionally speaking, those with a doctoral education are one of the most likely demographics to regularly attend church.9

Even further, the prevalence of atheism in modern science is nowhere near as bad as most assume. A study from Professor Elaine Ecklund found that less than a third of modern scientists thought faith was incompatible with science. Her later research found that the group who saw them as incompatible were exclusively those who didn’t grow up in religious environments.10

To top that off, here’s a graph to help illustrate how not opposed to science Christianity is:11

All to say, science isn’t religion’s anathema; and the whole idea that they’re incompatible actually stems from a popular myth.

3. An Abbreviated Overview of How Historians Made a War Between Religion & Science

The idea that faith and science can’t mix is pretty new. Some believe this view didn’t get going until the late 19th century.12

This is because “conflict thesis”— the idea that theology and science are inherently at odds — is only that old.

Conflict thesis is sometimes referred to as the “Draper-White narrative” after the historians who dreamed it up: John Draper and Andrew Dickson White.13

Their thesis piggybacked on the evolution controversy stirred by the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species a quarter-century prior. The two published a few barely peer-reviewed revisionist history books in the 1890’s, extolling the virtues of agnostic scientists who broke free from the clenches of religion:

The history of Science…is a narrative of the conflict between the expansive force of the human intellect on one side, and the compression arising from traditionary faith on the other.14

Fun fact: White & Draper are also the reason why most people believe that the average person thought the world was flat pre-Columbus, despite that Westerners had believed that the earth was round since the 5th century.15

Conflict thesis has been totally discredited: both today and even back then. Their contemporary, historian James Joseph Walsh, dismissed their work, writing that all it proved was how “easily even supposedly educated men may be led to follow their prejudices rather than their mental faculties.”16

The later historian Lawrence Principe wrote, “No serious historians of science can maintain the warfare thesis,” and criticized Draper and White for using “unreliable historical foundations.”17

Further, even Darwin himself wasn’t in on conflict thesis. Surprised by the concerns religious communities voiced after the publication of Origin, Darwin edited the introduction of the second edition to include a quote from the priest Charles Kingsley and the mention that his whole theory was only possible “by the Creator.”18

That’s how much religion isn’t opposed to science: the scientist who’s scapegoated as religion’s greatest enemy actually wasn’t much of an enemy.19

As contemporary historian Gary Ferngren put it, there’s a

growing recognition among historians of science that the relationship of religion and science has been much more positive than is sometimes thought. Although popular images of controversy continue to exemplify the supposed hostility of Christianity to new scientific theories, studies have shown that Christianity has often nurtured and encouraged scientific endeavour, while at other times the two have co-existed without tension.20

Professor Rivka Feldhay agreed, declaring that the historical relationship between science and religion was one of “symbiotic coexistence.”21

Recounting the huge popularity of White and Draper’s theory, Principe said the credit was due to their crafting of “a myth for science as a religion. Their myth of science as a religion is replete with battles, and martyrdoms, and saints, and creeds. And as we know, myths are often much more powerful than historical realities.”22

Which might just be the biggest reason conflict thesis has been called the “most successful conspiracy theory in history.” It was caricatured as a just war between the righteous scientists and the corrupt clergymen, and that made for a story good enough to bleed into the popular imagination.

So if you’re looking to blame someone for why a modern comedian like Ricky Gervais would build a whole standup special around making fun of Christians for their scientific idiocy, don’t blame Gervais. He’s just following the cultural script. Blame White and Draper.

4. The Role of Science in Faith

It’s not much an exaggeration to say that before 1.5 centuries ago, the majority of scientists believed in some idea of God. Lab experiments were often seen as just another way to fill in the blanks about the way God designed creation.23

Take this quote from a WWII engineer for example, “Only God invents; humans discover…[I’m] just one who discovers the greatness of God…God reveals truth through people who are willing to work hard and to use their minds to discover God’s truths.”24

This idea might seem novel to us but it wasn’t back then. Scientific study was often considered an extension of divine wonder.

Scientific discoveries teach about God because they reveal more about His craft – kind of like how analyzing a painting or movie can teach us about an artist’s headspace.25

When we frame it this way, it gives us a practical vision for how the sciences can work with theology.

Anyways, if you’re still reading, I assume you’re probably on board with where this is going: the continued divide between science and theology is nonsensical.

We should normalize their intersection insofar as we’re able; we need Christian scientists as much as ministers, astrophysicists as much as worship leaders.

And the best way to normalize a reintegration of science and faith might be to take advantage of the point where the two diverge.

As I mentioned in the intro, the two schools of thought have different interests, which guarantees they’ll always ask different questions.

The theologian Oliver O’Donovan uses the creationism example to illustrate this:

Whatever scientific researchers may believe they are able to tell us about the prehistory of the universe, they can tell us nothing about ‘creation’ in the theological sense, because creation is not a process which might be accessible through the backward extrapolation of other processes. Creation as a completed design is presupposed by any movement in time. Its teleological order, expressed in the regular patterns of history, is not a product of the historical process, such that it might be surpassed and left behind as history proceeds further towards its goal.26

Essentially, science can’t have authority over theology because its methods of measurement lack the tools that would make it capable of rewriting theological doctrine.

As the biochemist Arthur Peacocke put it, though “science and theology are compatible,” they “are two distinct non-interacting approaches to the same reality.”27

Put simply, the scientist asks “how” and the theologian asks “why.”

Science is the study of measurable things. It starts with a question and then makes however many measurements necessary to answer the question. If it can't be measured, it doesn’t fit under the banner of “science.”28

But God can't really be measured.29 Which means that science, by itself, can’t answer direct questions about God – or really any “why” questions concerning the nature of existence.

While science doesn’t have much to say about purpose or meaning, theology exists for meaning’s sake.

Science can explain how the brain produces passionate feelings of romance for 12-18 months, but can only speculate on why a couple continues to stick together after those 12-18 months are up. It can guess how the universe originated from a big bang 14.7 billion years ago, but only offers cause and effect explanations for the why behind it.30

Science makes measurements; theology creates meaning. If we could use theology to make sense of the sciences and use sciences to learn about the intricacies of God’s design, we might find a synergy between the how and the why, the measurements and the meaning.

This could also close the gap between spiritualized “belief” and academic “knowledge.” Spiritual knowledge and scientific knowledge could work together under the same umbrella of “true things about the universe.”

Which is, I think, the way it should’ve always been.

5. Making Sciences Work for Faith

For me personally, I try to keep this in front of my daily mind by grouping all of my research onto Arthur Peacocke’s hierarchy of academic disciplines.

In Peacocke’s (and my) worldview, theology is at the absolute peak of the hierarchy because it studies the most complex system of all: “the relation of God to all that is.”31

So when I’m researching, I mentally categorize the kind of information I’m taking in, making sure that I don’t assign things lower on the hierarchy interpretive authority over the things that place higher.

Like everything else on the hierarchy, the sciences are best employed as theology’s assistant rather than manager.

There’s a similar concept that floats around theological circles called “spoiling the Egyptians.” The idea comes from Exodus 12:36, when the Israelites plunder the Egyptians as they’re exodus-ing (sorry).

So “spoiling the Egyptians” became shorthand for the process where a Christian borrows a thought from outside the Christian tradition to help solidly a Christian argument. It’s like when Paul took ideas from philosophers like Seneca and Aratus and transformed them into truisms that pointed crowds back to God (Acts 17:21-30).

In a way, using scientific studies is a bit like “spoiling the Egyptians,” but I just dislike that language. Spoiling the Egyptians implies that the sciences didn’t belong to God in the first place.

Which is why I’d rather think about this in terms of “authority.” As Paul writes,

For the wisdom of this world is foolishness in God’s sight…So then, no more boasting about human leaders! All things are yours, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future—all are yours, and you are Christ’s, and Christ is God’s. (1 Cor. 3:19, 21-23; see also Matt. 28:17; John 16:13-15).

Paul criticizes the Corinthians for attaching themselves to singular teachers because, as people who are Christ’s, they have privileged access to the entire pool of existing knowledge. New Testament scholar Leon Morris translates this verse, “Why do you limit yourselves by claiming that you belong to a particular teacher? Do you not realize that all teachers, indeed all things that are, belong to you in Christ?”32

Or, in scholar Margaret Thrall’s words, “Every possible experience in life, and even the experience of death itself, belongs to Christians, in the sense that in the end it will turn out to be for their good.”33

Framed with this language, using scientific research becomes a way of taking what was already God’s and re-declaring it in His name through the Spirit’s authority.

Some think that using science shows a lack of faith. But it shouldn’t. Using other sources from the web of existing research is just another way to exercise your Spirit-given authority over all knowledge, taking all things captive for the glory of God.

Pew Research Center, "On the Intersection of Science and Faith," Pew Research Center, August 26, 2020.

For more on this, please see Dallas Willard, Knowing Christ Today: Why We Can Trust Spiritual Knowledge (San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins, 2014).

Quote lightly edited for clarity. Lesslie Newbigin, A Faith for This One World (London: SCM, 1961), 30.

Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who is There (The IVP Signature Collection) (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP, 2020 Reissue) 117.

Origen, First Principles II.11.4.

Freeman J. Dyson, Disturbing the Universe (New York: Harper & Row, 1979) 250.

Tozer and Kierkegaard were both passionate about this idea. I agree with them, but I’m not sure how far I’d take their conclusions.

I’m working on another project that dives into this more in-depth. But so far, I believe this inaccurate statistic originated in a Gospel Coalition article in 2019, but it was based off of a misreading of a Barna study.

Ryan Burge, 20 Myths about Religion and Politics in America (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2022), pp. 53-62; Ryan Burge, “There’s No Crisis of Faith on Campus,” Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/theres-no-crisis-of-faith-on-campus-11645714717. Rodney Stark has an interesting chapter chopping out the philosophy behind this phenomenon in Triumph of Christianity. See also Ryan Burge’s wonderful publication Graphs About Religion.

Elaine Ecklund, Secularity and Science: What Scientists Around the World Really Think About Religion (New York: 2009), 9-10; Ecklund, Park, “Conflict Between Religion and Science Among Academic Scientists?” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48 (2016): 276–292.

Ronald Numbers, Galileo Goes To Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 3.

See chapter 20 of John Dickson, Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2021).

John William Draper, History of the Conflict Religion, originally published in 1881.

S.J. Gould, “The Late Birth of a Flat Earth,” in Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History (New York: Crown, 1996), 38–52.

James Jospeh Walsh, The Popes and Science; the History of the Papal Relations to Science During the Middle Ages and Down to Our Own Time (New York: Fordham University Press, 1908), 19.

Lawrence Principe, Science and Religion (New York: The Teaching Company, 2006), 7.

Janet E. Browne, Charles Darwin: Vol. 2 The Power of Place (London: Jonathan Cape, 2002), 96.

One reason Darwin is scapegoated as an enemy of the faith is simply because the second edition of On the Origin only printed about 3,000 copies; scarcely enough to influence the already transforming plausibility structures. My former professor Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen did some incredible work in this area. See his Christian Theology in the Pluralistic World: A Global Introduction (United Kingdom: Eerdmen’s, 2019) 130-150.

Gary Ferngren, Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction (Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), ix.

Rivka Feldhay, “Religion,” in The Cambridge History of Science, Vol. 3: Early Modern Science (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 727.

Principe, Science and Religion, 2.

See Christopher C. Knight, Science and the Christian Faith: A Guide for the Perplexed (Cambridge, UK: St. Vladmir’s Seminary Publishers, 2021).

Malcolm Gladwell, The Bomber Mafia: A Dream, a Temptation, and the Longest Night of the Second World War (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2021) 24.

See Roger Wagner & Andrew Briggs, The Penultimate Curiosity: How Science Swims in the Slipstream of Ultimate Questions (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Yeah, I love O’Donovan, but he’s not a champ when it comes to clarity. Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and Moral Order: An Outline for Evangelical Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2nd edn, 1994), 63.

Arthur Peacocke, The Sciences and Theology in the Twentieth Century. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981), xiii-xv.

Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007).

However, our human experience of God can be measured, which accounts for many fascinating studies that have been popping up in the past half-century about the neurological relationship that humans can have with God.

Kärkkäinen, Christian Theology in the Pluralistic World, 141; Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness, Ch. 1; Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, “Natural Sciences on the Origins and Evolution,” pg. 2.

See Arthur Peacocke, Theology for a Scientific Age: Being and Becoming (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1993).

Leon Morris, 1 Corinthians (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 1985), 74.

Margaret E. Thrall, The First and Second Letters of Paul to the Corinthians (Cambridge University Press, 1965; Cambridge Bible Commentary).

Really great, bro. I remember how difficult it felt going from K-12 Christian school to a state university with 50,000+ students, and how intimidating it was when a lot of really intelligent people seemed to hold beliefs that I thought were contradictory to my fundamental view of the world.

Ironically, it was a conversation with my Cell and Molecular Biology professor freshman year of college that spurred a years-long journey delving into the “science vs. faith” conversation. He was really the first one to introduce me to the idea that you can love science and the exploration of the natural world and also have a deep and meaningful faith in God (and I’m not convinced he was even a believer himself).

I began to view my studies through a Genesis 1 lens - every time I sit down to study, I am fulfilling my vocational call of having dominion over creation. Simply knowing the ins-and-outs of how the world works feels to me like a form of dominion, but in another sense, when I read about the intricacies of a bacterium, or a cancer cell, I can see how to treat it, or how to “rule over it”. Realizing that faith and science are the greatest complements of one another has been the best gift through 4 years of medical school!

Helpful! As a physics teacher in a Christian school environment, I’m going to share your Nobel pie chart with my students. You mentioned Charles Kingsley and Darwin. Interestingly, Kingsley wrote a book actually called “Madam How and Lady Why” in the 1800s which tries to reconcile the roles of science & faith similarly to how you do later in your article.