No One Feels Successful, No Not One

On Lying About Your Age, Achievement Anxiety, and How to Really Feel Successful

1. Fabricating a Fountain of Youth

Last year I started noticing a strange temptation that would bubble up while meeting new people. For some reason, when asked how old I was, I’d take a few milliseconds to consider lying about my age.

Which, yes, was odd.

But I think I was just hoping to preempt the eventual follow-up question: “So what do you do?”

I care more than I’d like to admit about how I’m perceived by others. And one evergreen component of this concern is the fear of falling behind in terms of career or life track.

So my wanting to forget a few recent birthdays was just a misguided attempt to avoid the glazed-eye nods that come after explaining that I’m still in school and don’t have an illustrious career in reach.

My reasoning: if I was a few years younger, that’d probably mitigate potential judgement.

And yes, the impulse was enormously self-serving. So I ignored it.

But like most impulses ignored rather than dealt with, it kept resurfacing. So I tried to contemplate it more thoroughly.

I found a shocking number of articles, opinion pieces, and Reddit threads that discuss the phenomenon of lying about age. From multiple perspectives, too: psychological, neurological, philosophical, physiological, etcetera.1

It’s way more normalized than I expected. To boil down the general rationale behind the findings, we lie about age to (1) look impressive and (2) ignore mortality.

2. Look Impressive, Ignore Mortality

I doubt anyone needs much empirical data to convince them that being young and successful is generally more desirable than the opposites those two variables. Achieving things when you’re young affords you security about your social status.

When the writer Lena Dunham turned 25, she wrote a birthday episode for her Girls character to convey the stomach churn Dunham felt at her real life 25th birthday. “My friend and I were like, ‘No one will ever consider us precocious again.’ After 25, nothing you do makes people say, ‘Wow, what’s it like to be so young and successful?’”2

This aura of a young savant is enviable enough to make watering down age common parlance across several industries. And according to some of the research, the temptation to present ourselves younger is starting younger – with some preteens even starting to trim a few years off their age.3

Surveys find that 64% of the lies we tell have to do with personal accomplishments – including the ages at which things were accomplished.4

Take for example Jessica Richman, the founder of the biotech company uBiome. In a Business Insider interview, Richman claimed she was still “under 30.” Which was a suspiciously direct statement that cued editors to throw her on a “30 Under 30” list.

However, Richman was 40 at the time of the interview.5

Five years later, Richman again lied to make her way on a “healthcare leaders under 40 list,” where most people who remembered her (and also had learned to count) weren’t surprised to find she was 45.

“Age is just a number – especially if you lie about it.” – Elle Hunt

Of course, this wasn’t ethical or wise – but to me Richman’s lying seems less like a selfish scheme than an unhealthy coping mechanism for the anxieties of a pressure-driven industry.

You can even find Ivy League professors doing the same things.6 Some psychologists go as far as recommending that you should lie about age because it might trick your body into being more energetic.7

Which, coming from a profession that’s made more difficult without a patient’s literal age, seemed like surprisingly unethical advice. But apparently (and unfortunately) bending morals to serve our own egos isn’t an uncommon response to social anxieties.

Researchers at the University of Duisburg-Essen found that while stress doesn’t have much influence on everyday moral dilemmas, it has a profound effect on “egoistic decisions” (i.e., the kinds of decisions that might boost our own self-esteem).8

Maybe this is why Renè Girard said that the ego itself is “made up of nothing but a thousand lies that have accumulated over a long period, sometimes built up over an entire lifetime.”9

So, as social pressures increase, certain ethical no-brainers (like lying to posture a higher status) will seem more fluid.

And according to Professor Thomas Curran, author of The Perfection Trap, these “socially prescribed pressures” are “rising really, really quickly.”10

The journalist Jennifer Breheny Wallace, with help from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, found that the chronic anxiety of high-achievement culture might be affecting as many as 1 in 3 individuals – with the sufferers skewing proportionally toward teens and young adults.11

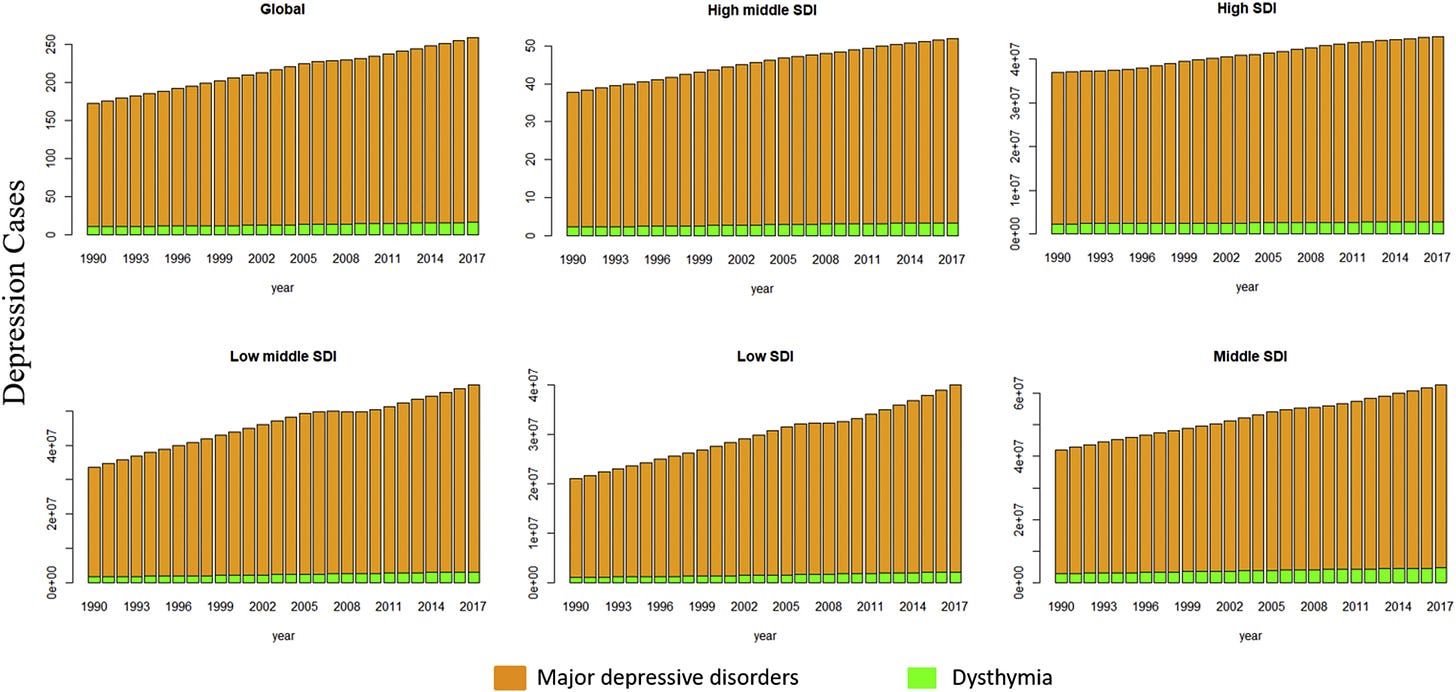

Its effects aren’t hard to spot. In 1979 the average age someone would get diagnosed with depression was 29. Thirty years later, it dropped to 14.12 Another meta-analysis found a 49.86% increase in depression from 1990 to 2017.13

While other factors were likely involved (loneliness, social media, etcetera), this does happen to fall in the exact timeframe where achievement culture really kicks in.

But even though these anxieties surrounding achievement might seem novel, they aren’t entirely unique to right now. Examples overfloweth:

Vincent van Gogh was famously tortured by his lack of achievement, even describing his mood in a way that feels eerily similar to modern achievement anxiety: “I am always in pursuit of something greater, but it seems as though it is always just beyond my grasp. Time moves too quickly, and I wonder if I will ever catch up with my dreams.”14

Sylvia Plath wrote similarly, “The future terrifies me. There is this doubt: What if I can't ever write something great? What if I can't ever accomplish what I dream of? And what if it is already too late?”15

The poet John Keats likened his fear of dying before fully realizing his creative vision to unharvested grain:

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain,

Before high-piled books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripened grain;16

All to say, achievement anxiety isn’t anything new.

But what makes this modern achievement anxiety unique is that we don’t just believe that we have to meet unrealistic standards – we also believe we should meet those standards by unrealistic ages.

Our culture hallows the image of the young and successful. It’s become our paragon of status. So it only makes sense that missing that mark would cause some comparison-induced frustration.

But I do think there’s another kind of sadness laced under this, and it’s a sadness that stems not just from idealizing early success but youth itself.

Our world is youth-obsessed. Everything from our advertisements to films to music to Instagram influencers caters around the young.

Maturity isn’t assigned any glamour. In the popular imagination, happiness is maximized in proportion with however long we can prolong adolescence, having children, or committing to responsibilities.

In this ethos, aging can be experienced as its own kind of death—it can feel like you’re growing beyond the proximity of cultural relevance. So, many choose to fabricate staying young rather than deal with the normal consequences of time.

Perhaps this is why Heathline and similar outlets have released treatment plans for “Peter Pan Syndrome” and why writers like

are putting out articles discussing the need for adults.Ignoring maturity brings consequences that aren’t as easy to ignore. Our kids and younger friends need models to teach them what maturity looks like – and so do we.

Perpetual adolescence isn’t anything like its depicted on TikTok – when it happens around you, it’s heartbreaking.

We all know the melancholic awkwardness from hanging around someone who’s ignored the responsibilities of aging: nodding solemnly with your old roommate who hasn’t realized they kept up the college party lifestyle way too long after graduation, forcing smiles through a friend’s plastic surgery, getting vaguely annoyed with the couple that wasn’t right for each other yet too lazy to break up and so they wasted a decade of each other’s time in a preventable purgatory, the pang of noticing a son who never learned to grow up because his father never showed him how.

Eternal youth is experienced as more of a curse than blessing. This is partly because youthfulness is almost pathologically interior. Despite our cultural beliefs in the benefits of self-care, research shows that the best kind of self-care is caring for others.17 Which goes to show that the more we push our attention inward and reject responsibilities (i.e., the primary characteristics of youth), the less satisfied we’ll feel in general.

This inward attention also creates an inferiority complex. It turns our brain into a status-detection system that perpetually measures itself against arbitrary benchmarks.

Ironically, if we just accepted the invitations of growing up, we’d gain the emotional maturity to care less about how we’re perceived by others. Adulthood is seen as the problem when it’s really the solution.

3. How to Feel Successful

Lastly, all of this research brought me to another point: as far as I can tell, no one feels successful.

Everyone is self-conscious to some degree.18 Even of the most impressive people I’ve talked with – the head of one of the most successful churches in the country, a writer with four NYT bestsellers under his belt, a couple that made their first million before they were 21, a man who invented a medicine that the majority of the Western world has taken at least once – none of them really felt “successful.”

As the founder of Starbucks wrote, “Very few people, whether you’re a high school teacher or a CEO, wake up one day feeling like they’ve got everything figured out. Most of us are walking around feeling like we don’t belong.”

This is partly because success is entirely relative. The idea of “success” only exists because we use other people as benchmarks. And it’s impossible to top the ladder in every area of life; there will always be someone more fit, kind, popular, wealthy, beautiful, or powerful.

Even if we were four steps ahead of where we are right now in terms of career, family, or achievement, there’s a decent chance that we still wouldn’t feel satisfied. To paraphrase the authors of Scripture, “No one feels successful, no not one” (Rom. 3:10).

However, one way we can feel successful is simply nominating to restore a sense of dignity to growing up — to act as though the less glamorous aspects of adulthood are actually desirable.

Further, I’ve also tried tossing out the hope that some arbitrary level of achievement could satisfy once for all. The dichotomy that splits the population into camps of successful and unsuccessful is a false one. And so is the idea that success should correspond to age.

For better or worse, you were born on the day you were born. Insisting that we should be further along career-or-relationship-wise distracts us from cherishing whichever moment in time we find ourselves.

Fabricating a younger persona ignores the new opportunities that come with your age; and although life’s new invitations might seem less glamorous as they did at 21, the new ones push you to become incrementally freer from the shackles of achievement anxiety.

As the Proverb goes, “The glory of young men is their strength, but the splendor of old men is their gray hair” (20:26). Every stretch of life is entitled to a unique dignity insofar as we’re willing to lean into its invitations.

So I think the best thing we can do is be the age we are, accept reality as is, and use whichever potentials God’s placed in us to the best we’re able, right now.

Thanks for reading! This is a companion piece to my Fare Forward article that came out a few weeks ago.

The most interesting was likely Gina Barreca’s.

Lena Dunham, via post-episode commentary on “She Said OK,” Girls, S3E3, Max.

Wayne Delfino, “The Science of Lying About Your Age: How Picturing Yourself As Younger May Help You Live Longer,” Medium, August 28, 2017, https://medium.com/thrive-global/the-science-of-lying-about-your-age-how-picturing-yourself-as-younger-may-help-you-live-longer-ea2380f2f826.

Bright Futures, “Statistics About Lying (2023),” https://www.brightfuturesny.com/post/lying-statistic; Serota, K.B., Levine, T.R., & Boster, F.J. (2010). “The prevalence of lying in America: Three studies of self-reported lies,” Human Communication Research, 36(2): 2-25; Levine, E.E., Schweitzer, M.E., Galinsky, A.D., & DeCelles, K.A. (2018). “Can Dishonesty Breed Trust? The Consequences of Lying for the Subsequent Cooperation of Others.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76: 405-413.

Elle Hunt, “Age is Just a Number – Especially if You Lie About It,” The Guardian, May 21, 2019, https://amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/may/21/age-is-just-a-number-especially-if-you-lie-about-it.

Gina Barreca, “Do You Lie About Your Age?” September 15, 2015, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/snow-white-doesnt-live-here-anymore/201509/do-you-lie-about-your-age?amp.

Isla Rippon and Andrew Steptoe, “Feeling Old vs Being Old: Associations Between Self-Perceived Age and Mortality,” JAMA Intern Med 175 no. 2 (2015):307-309.

Katrin Starcke, Christin Polzer, Oliver T. Wolf, Matthias Brand, “Does stress alter everyday moral decision-making?” Psychoneuroendocrinology 36 no. 2 (2011): 210-219.

Renè Girard, When These Things Begin: Conversations with Michel Treguer, trans. Trevor Cribben Merrill (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2014), 129.

See Thomas Curran, The Perfection Trap (New York: Scribner, 2023); see also Emily Sohn, “Perfectionism and the high-stakes culture of success: The hidden toll on kids and parents,” American Psychological Association 55 no. 7 (2024): 54.

Jennifer Breheny Wallace, Never Enough (New York: Sentinel, 2023), xiv-xvi.

Shawn Achor, Big Potential (New York: Crown, 2018), 11.

Qingqing Liu, Hairong He, Jin Yang, Xiaojie Feng, Fanfan Zhao, Jun Lyu, “Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study,” Journal of Psychiatric Research 126, 2020: 134-140.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, ed. Mark Roskill (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), 344.

Sylvia Plath, The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 1950-1962 (New York: Anchor Books, 2000), 272.

And it is a bit sad that he did actually die before realizing his vision. John Keats, The Complete Poems and Selected Letters of John Keats, edited by Robert Gittings (New York: Modern Library, 2001), 135.

Frank Martela & Richard M Ryan, “The Benefits of Benevolence: Basic Psychological Needs, Beneficence, and the Enhancement of Well-Being.” Journal of Personality 84 no. 6 (2016): 750-764.

See Mark Leary, The Curse of the Self (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Before I quit my job as a corporate lawyer, I was making well over $200k at 27 years old and had graduated from a top law school etc. I was also completely miserable and less confident than ever. It's tough - I was raised in a competitive environment and molded to reach the top echelons of academic success (and since I didn't go to Yale, Harvard, or Princeton I technically "failed" at that). But once it happens, you're like the dog that's caught its tail and you often don't know what to do. So much of your identity is bound up in getting somewhere and then when you get there it's confusing because you're still the same person and life is still hard.

I'm sure this is different for men and women so that's another layer of it but the emphasis on intelligence and high achievement was not good for me. I was only able to relax once I was able to let go of it all and stay home with my son.

I feel sad that so many feel this intense pressure to 'appear' successful. I've never achieved the world's standards of success (not even close), but now in my 70's I am learning the importance of simple contentment. I'm not there yet, but am learning that being peace-filled is more desirable than being successful. God bless and keep you, Griffin!