Why Connection Makes Life Worth Living

Harvard Study of Adult Development, Dopamine Soteriology, and Why We Can’t Thrive Without Relationships

1. The Opposite of Addiction

My friend Matt got off heroin, for a while.

About 12 years ago, he met Jason and Amanda at a recovery program. They were full-time local missionaries through a nearby church. Matt was court ordered to attend, Jason and Amanda were there simply to build relationships.

When Matt graduated from the program, he went right back to heroin. Strung out one night, he sent a text to Jason, the kind of text where there’s little question as to the sender’s sobriety. The next day, Amanda called Matt and told him to come live with them.

And so he did. After that call, he sobered right up. He found Jesus, as many in his situation do. Eventually Matt moved from their house to another down the street and kept in close contact.

All was well until he hit a crisis that left him feeling like both God and his friends abandoned him. They didn’t, of course; but it genuinely felt like they did.

Jason and Amanda’s tried to stop him, but he moved away. Then Matt cut off the rest of his connections and eventually started using again.

I’m describing this episode casually, but it really was one of the more depressing story arcs I’ve seen in my adult life.

And yet it was blisteringly realistic. It rolled out almost exactly as anyone who’s studied addiction would’ve predicted. When our relationships dissolve, so does our sense of stability. Then everything else slowly chips away.

As the science journalist Johann Hari put it, “The opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety. The opposite of addiction is connection.”

It’s easier to stay sober, resist temptation, and live a moral life when we’re living in genuine connection to a loving community.

And this is mainly because, whether we realize it or not, deep relationships are fundamental to a healthy, happy life.

2. Oxytocin > Dopamine

If you had to draft a list of things that make you happy, what would you include?

Money? Achievement? Entertainment?

Among Westerners, these answers are typical. Riches and fame pop up on well over 50% of surveys.1

Two things that rarely end up on their lists?

Connection and suffering.

But, as it turns out, if we were actually looking for happiness, then we’d probably want to put these two near the top of our priorities.

However, we only seem to notice the power of connection and suffering in hindsight.

Sure, we probably enjoy hanging out with friends or family; but it’s not until the back half of our lives that we realize how meaningful those relationships were. This is why one of the most common deathbed regrets is, “I wish I stayed in touch with my friends.”

And by “suffering,” I’m not referring to torture; I’m referring to what Carl Jung called “necessary suffering.”2 It’s essentially any and every kind of collateral we face while pursuing long-term goods, such as character growth, love, or creative endeavors.

As Jung noted, by putting off life’s necessary sufferings, we cause ourselves far more unnecessary sufferings (i.e., suffering via our own lack of maturity, the wasting of our talents, or neglecting meaningful relationships).

Unfortunately for us moderns, understanding the value of connection and suffering is harder than ever thanks to the increasing infatuation with instant gratification.

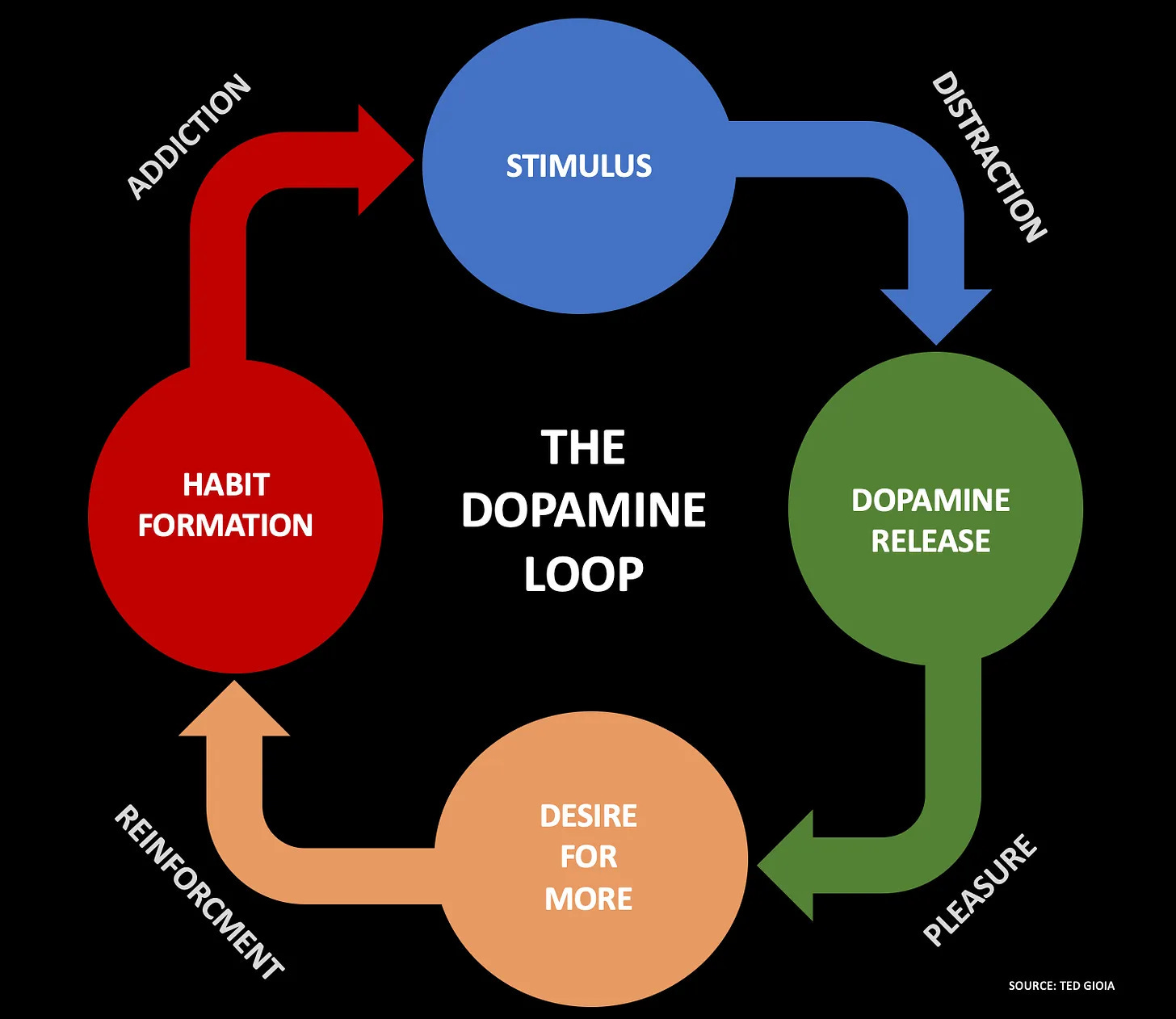

According to psychiatrist Anna Lembke (and Ted Gioia’s exceptional article building off Lembke’s work), our culture is drifting toward quicker and quicker gratifications (or dopamine loops) because they’re simply more enjoyable than reality.3

Life is hard, mundane, challenging; dopamine loops are like an easy-access opiate for the burden of living.

Just consider how many facets of modern life now feel like a slot machine: open YouTube to check for new subscribers, refresh email in case there’s any potential résumé boosters, window shop for romance via any of the literal 1,508 available dating apps.

Instead of considering dopamine a natural reward or side effect from our pursuit of higher values (which is exactly how we should think of dopamine), many of us treat dopamine as the higher value itself.

In other words, dopamine has become our cultural soteriology – or “theory of salvation.”

It promises relief from our bottomless pit of wanting (i.e., what Pascal called our “God-shaped hole” in our hearts) while secretly reinforcing its hunger.

Perhaps dopamine soteriology’s best deceit is creating the delusion that an eternal plateau of happiness is attainable through higher spikes pleasure.

This is way off base. Dopamine can’t save us. And behaving as if it can only takes us further from finding real satisfaction.

The more time and energy these dopamine loops eat up, the less we have leftover to invest in connections and necessary sufferings.

Put another way, if we’re feeling down, the assumption is that dopamine will lift us up. In actuality, this is like trying to relieve a headache by taking Claritin.

If anything, dopamine soteriology is less responsible for our happiness than it is culpable for our record levels of unhappiness.4

Part of what perpetuates this issue is that dopamine is thought of as the “happiness chemical.”

In reality, dopamine is just one of four “feel-good”5 hormones, along with endorphins, serotonin, and oxytocin.

However, even though these hormones cause positivity, the satisfaction that they provide (especially dopamine’s) is quickly replaced by a crash or withdrawal.6

But oddly enough, the one hormone of the four that incentivizes the most lasting happiness is the one we’d probably think of as the least important:

Oxytocin.

Also known as the “love hormone,”7 oxytocin is a neuropeptide we produce in response to (and to help facilitate) trust, bonding, and social connection.

As such, the calm, agreeable, and comforted state it puts us in contributes far more to a feeling of visceral contentment and non-anxiousness than any dopamine rush ever could.

3. The Harvard Study of Adult Development

The best way to see why oxytocin is so vital is through the longest lasting study in history: the Harvard Study of Adult Development.

If you’re unfamiliar, just Google it. It’s wicked cool.

Starting in 1938, this program took a group of 268 Harvard sophomores and 456 inner-city Boston kids and began tracking their lives: their friendships, romances, addictions, jobs, educations, and levels of happiness.

And they kept this up for eighty-six years. Meaning, the study is still going. It’s continued through multiple generations by following the original group’s children and children’s children.

Unlike typical studies, which tend to focus on how someone becomes unhealthy, this study asked the opposite question: how does someone become healthy?

As the study’s two current leaders, Robert Waldinger and Mark Schulz, wrote

For eighty-six years (and counting), the Harvard Study has tracked the same individuals, asking thousands of questions and taking hundreds of measurements to find out what really keeps people healthy and happy. Through all the years of studying these lives, one crucial factor stands out for the consistency and power of its ties to physical health, mental health, and longevity. Contrary to what many people might think, it's not career achievement, or exercise, or a healthy diet. Don't get us wrong; these things matter (a lot). But one thing continuously demonstrates its broad and enduring importance: Good relationships.8

Did you get that? Scientists at one of the most prestigious universities in the world boiled down nearly a century of research to find that the good life comes through solid social connections!

Isn’t that insane?

This goes completely against our cultural ideas of what makes us happy. In fact, the study’s least happy members were those who sacrificed good relationships for the sake those popular beliefs about happiness.

Even further, those who had the least secure connections were also more likely to struggle with poor health, drug abuse, and legal issues.

In other words, it’s hard to live a good life without strong connections.

And one hormone produced through relational encounters – be it parent-child attachments, romance, a fifty-year marriage, or friends from college catching up over a beer – is oxytocin.

Oxytocin then helps us double down on our connections by strengthening our sense of trust toward them.9 It’s like chemical confirmation of the beauty of community.

As George Vaillant, one of the study’s original directors, summarized, “There are two pillars of happiness revealed by the Harvard Study. One is love. The other is finding a way of coping with life that does not push love away.”10

That last point, “coping with a life that does not push love away,” makes a helpful clarification.

All forms of connections are great, even the casual ones. But we won’t be content with surface level relationships forever; therefore, if we want to get the most out of connection, we have to make peace with the necessary sufferings packaged with deep emotional connection.

4. The Necessary Sufferings of Relationships

Take Henry and Rosa for example. Henry was one of the inner-city Boston kids from the very beginning of the study. He had a tough upbringing in a tattered family “led” by an alcoholic father. He moved to Michigan after high school to work at General Motors.

He met Rosa there and got married soon after, having five children in quick succession. But one of them got polio and the medical bills drained their savings. Then Henry got laid off and the family struggled to make ends meet.

Despite all the adversity, the family made it through. Not only did they survive, but they also got recorded as some of the study’s happiest participants.

When one of the study’s researchers flew to Grand Rapids to interview Henry and Rosa, now in their late 70’s, she asked them, “What is your greatest fear?”

“Spiders,” Rosa answered quickly. Henry looked uncomfortable and tried to shift the conversation. When they pressed him to answer, he told them he didn’t want to, he was embarrassed.

Finally, after they coaxed him enough, he reluctantly answered:

“That I won’t die first is my fear. That I’ll be left here without Rosa.”

Neither the researcher nor Rosa knew what to say.

In one sense, Henry’s response shows us that relationships are a centerpiece of a purposeful life. But it also reveals the anxieties of allowing ourselves to love without reservation.

As the author Elisabeth Eliot put it, “To love means to open ourselves to suffering.”11 Permitting ourselves to love anything requires the simultaneous acceptance of the anxiety surrounding its loss.

Which is why some prefer to guard themselves from love altogether. From a perspective of strictly pragmatic emotional accounting, it is technically safer.

But to preserve ourselves from love is no way to live.

As C.S. Lewis wrote,

To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket – safe, dark, motionless, airless – it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable.12

We could scarcely call this “living.” The tensions of love – the risk, uncertainties, and vulnerability – are the very costs that make it palpable and worth enduring.

There’s a psychological reality to the quote falsely attributed to Shakespeare: it is literally better to have loved than to never have loved at all.

5. God and You

While connection with other humans is necessary, our connection to God is, in my opinion and worldview, the most important connection fathomable.

And this is partly because our relational understanding of who God is – whether He’s personal or distant, loving or wrathful – has an enormous effect on who we are and who we’ll become.

Everyone’s heard the Tozer quote a million times but just bear with it: “What comes to mind when we think about God is the most important thing about us.”

This isn’t exaggeration or hyperbole. For example, those who believe in God (and thus see the world as meaningful) find much more purpose in their everyday lives than those who think of God as nonexistent (and thus see the universe as purposeless).13

The qualities we ascribe to God, even if we refuse His existence, can’t not shape who we become.

Many research projects have come to similar conclusions:

For example, adults with more mature and healthy relationships tend to experience God as loving and benevolent.14

Conversely, adults with less stable relationships are more likely to picture God as wrathful, irrelevant, or controlling.

Apparently when researchers studied brain activity in those who lose their faith or deconstruct, it was nearly identical to the experience of cutting off human attachment relationships.15

Patty Van Cappellen’s studies even found that meditating on God’s presence produces similar levels of oxytocin as found in human-to-human relationships.16

Lots of research on this subject confirms that our relationship with God “corresponds” to our human relationships – as in, if we’ve learned healthy attachment patterns through our parents or friends, those attachments will carry over to our relationship with God.

But according to some experimental research, our relationship to God can also “compensate” for relational pain or absence – as in, if we have unhealthy attachments, God can fill in those emotional gaps by transforming our attachments for the better.17

All to say, we still need human community; but for any relational deficiencies we experience — whether in the past, present, or future — God can compensate as a sort of substitute attachment figure.

And the best part is, He can even repair our relational attachments by existing as a sort of relational North Star — a perpetual example how perfect love envelops us.

6. Call Your Parents When You Think of Them

To circle back around to the intro, I wish I could say Matt was doing better. But life is strange, and doesn’t grant happy endings at the same rate as Hollywood. I still pray for him, but he doesn’t talk to us anymore.

But as someone who’s been around both churches and rehab facilities (which have an alarming number of similarities), this cycle is something I’ve gotten used to. We show up to community in desperation, it helps for awhile, the honeymoon phase withers, we hit turbulence, we recede from community, and then slide back into our vices.

So then, rather than give up or get cynical, I’ve tried to keep a new question in focus: how do we build deep enough commitments that we stick with our communities through thick and thin?

So far, I haven’t found any easy answers. The author of Hebrews called this tendency to fall out of community a “habit” (Heb 10. 24-25). Perhaps the temptation to recede from intentional community is simply perennial.

But my best bet is that kicking this habit requires believing that the benefits of sticking with our imperfect communities really does outweigh the unpleasantness of sustained vulnerability (or the dullness of setting aside our dopamine loops of choice long enough to immerse ourselves in community).

Yet, whether via the hard way or easy way, we all inevitably come to the conclusion that we need others. We’re not an island – or, at least, not a very good one. As we grow older, so grows our awareness of our need for one another.

So no matter where you are in life — whether you’re in a tight-knit community or a living case study of the loneliness epidemic — there’s a perfect first step to take.

After boiling down 86 years of research, Waldinger and Schulz answered a question they receive often: if you’re looking to set yourself on the path toward good life, what’s the best first step?

Think about someone, just one person, who is important to you. Someone who may not know how much they really mean to you. It could be your spouse, your significant other, a friend, a coworker, a sibling, a parent, a child, or even a coach or a teacher from your younger days. This person could be sitting beside you as you read this book, they could be standing over the sink washing dishes, or in another city, another country. Think about where they stand in their lives. What are they struggling with? Think about what they mean to you, what they have done for you in your life. Where would you be without them? Who would you be?

Now think about what you would thank them for if you thought you would never see them again. And at this moment-right now—turn to them. Call them. Tell them.

This is technically part six of a series on happiness. If you missed them, here’s part one, two, three, four, and five. One more installment to come (somewhat) soon (probably).

Jean M. Twenge, et al. “Generational Differences in Young Adults' Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966-2009,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102, no. 5 (2012): 1045-1062

Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion Volume 11: West and East (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2nd edn., 2014) Paragraph 129

Ivana Saric, “U.S. Hits New Low in World Happiness Report,” Axios, March 19, 2024, https://www.axios.com/2024/03/20/world-happiness-america-low-list-countries#.

Stephanie Wilson, “Feel-Good Hormones,” Harvard Health Publishing, April 18, 2024, https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/feel-good-hormones-how-they-affect-your-mind-mood-and-body.

While the hangover effect is very true for dopamine, it is less so for serotonin, and even further less so for endorphins.

Inga D. Neumann, “Oxytocin: The Neuropeptide of Love Reveals Some of Its Secrets,” Cell Metabolism 5 no. 4 (2007): 231 – 233.

Robert Waldinger & Marc Schulz, The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023), 10.

Heon-Jin, et al., “Oxytocin: The Great Facilitator of Life,” Progress in Neurobiology 88 no. 2 (2009): 127-151.

George Valliant, Triumphs of Experience (Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press, 2015), 50.

Elisabeth Elliot, The Path of Loneliness (New York: Revell, 2007).

C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves (London, UK: Geofrey Bles, 1960).

Stephen Cranney, “Do People Who Believe in God Report More Meaning in Their Lives? The Existential Effects of Belief,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52 no. 3 (2013):638-646.

Beth Fletcher Brokaw and Keith J. Edwards, “The Relationship of God Image to Level of Object Relations Development,” Journal of Psychology and Theology 22, no. 4 (1994): 352-71; Todd & Elizabeth Hall, Relational Spirituality: A Psychological-Theological Paradigm for Transformation (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2022), 121-130.

Lee A. Kirkpatrick, "Attachment and Religious Representations and Behavior," in Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, ed. J. Cassidy and P. R. Shaver (New York: Guilford Press, 1999), 803-22; Marie-Therese Proctor, “The God Attachment Interview Schedule: Implicit and Explicit Assessment of Attachment to God” (unpublished PhD diss., University of Western Sydney, 2006).

Patty Van Cappellen, et al., “Effects of Oxytocin Administration on Spirituality and Emotional Responses to Meditation,” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 11 no. 10 (2016): 1579–1587.

This conceptual framework was introduced by Lee Kirkpatrick. See Lee A. Kirkpatrick, "An Attachment Theory Approach to the Psychology of Religion, The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2 (1992): 3-28. See also Hall, Relational Spirituality, 144-146; Pehr Granqvist, "Religiousness and Perceived Childhood Attachment: On the Question of Compensation or Correspondence," Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37, no. 2 (1998): 350-67; P. Granqvist and B. Hagekull, “Religiousness and Perceived Childhood Attachment: Profiling Socialized Correspondence and Emotional Compensation,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38, no. 2 (1999): 254-73; L. A. Kirkpatrick, "God as a Substitute Attachment Figure: A Longitudinal Study of Adult Attachment Style and Religious Change in College Students," Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 24, no. 9 (1998): 961-967; Steven J. Sandage et al., “Attachment to God, Adult Attachment, and Spiritual Pathology: Mediator and Moderator Effects,” Mental Health, Religion e Culture 18 (2015): 795-808; Beth Fletcher Brokaw and Keith J. Edwards, "The Relationship of God Image to Level of Object Relations Development, Journal of Psychology and Theology 22, no. 4 (1994): 352-71. There are many more studies in relation to this theory, but this is not an academic work.

Thank you for this essay, Griffin.

You write, "So then, rather than give up or get cynical, I’ve tried to keep a new question in focus: how do we build deep enough commitments that we stick with our communities through thick and thin?"

I know this isn't a popular answer in our current cultural moment, but I think that something that helps is not being able to so easily leave a community. One way that communities were held together in the past was through geography, and the often insurmountable costs of moving away from a geographically-bound community.

No man is an island, as you note, but I live on a very small island. It's not like it's impossible to come and go, but it's much harder than it is in, say, the continental USA. I think this helps us to love our neighbors more.

One especially vivid example: in 2020, our island's response to pre-vaccine, pre-drug COVID was to shut down external travel to the island. So you could leave, but it was difficult (not impossible) to come back. This did allow us to live in a COVID-free bubble, with just five cases between January 2020 and December 2021. There was no masking, social distancing, lockdowns, etc. So, that was cool--but it also meant that no one could really go anywhere, and our tourist-sector economy was really suffering.

So what do you do with the neighbor who's really getting on your nerves with his horrible music? Invite him to play at the party you're throwing. What do you say to the neighbor who you're fighting with over vaccinations? That you would be honored to help with her community-wide cleanup. It's not like you have anything else to do, or anyone else to hang out with. You'd better learn to love your neighbor, or you will be really bored.

Love these insights. I have been thinking along the same lines when considering generosity. For pretty much my entire life I’ve heard some version of “if Christians only gave more”, almost always with the undercurrent being Christians aren’t generous enough - or greedy. I think rather than more law (you should do more) we need more joy (giving is better than receiving). And a key component to experiencing this joy is relational giving (less people between your gift and the recipient). That’s my hypothesis anyways :)